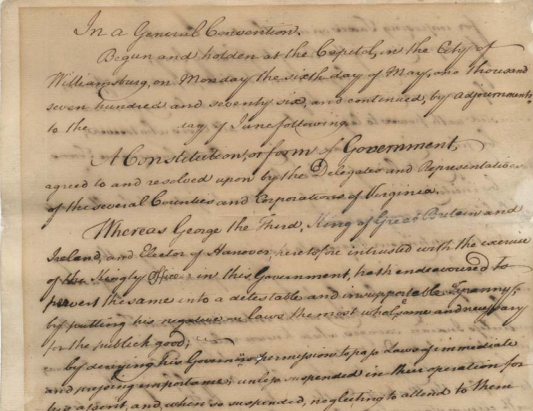

the Fifth Revolutionary Convention proclaimed Virginia's first constitution on June 29, 1776

Source: Library of Virginia, First Virginia Constitution, June 29, 1776

the Fifth Revolutionary Convention proclaimed Virginia's first constitution on June 29, 1776

Source: Library of Virginia, First Virginia Constitution, June 29, 1776

The 1776 state constitution was never submitted to the voters for ratification. It was "proclaimed" to be in effect by the same people who wrote it at the Fifth Revolutionary Convention. Proclaiming the document to be in effect was logistically simpler than holding another election during wartime. Proclaiming the new organic law, the foundation for a state government not based on the authorities of Parliament and the king, minimized the time Virginia was in a "state of nature" without a legal basis for its existence.

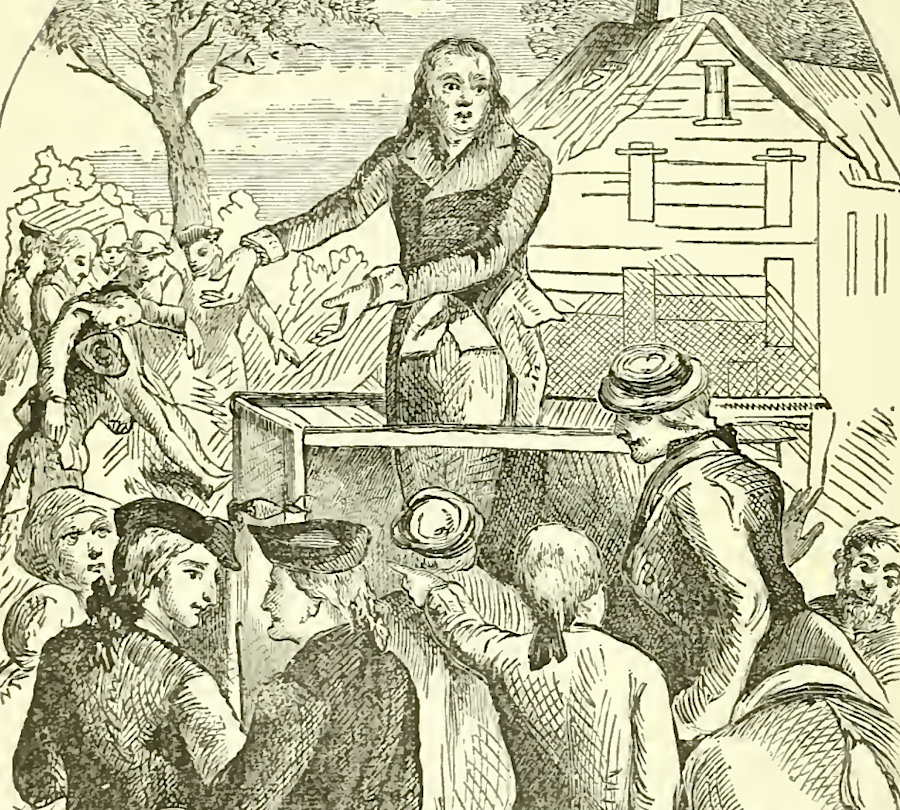

If the new constitution had been sent to the voters for approval, they would have been required to say out loud in front of all the spectators at each county courthouse whether they supported/opposed the constitution. Virginia held viva voce elections at that time, and anyone voting against the constitution would have exposed Loyalist sentiment.

The rebel leaders of the Fifth Revolutionary Convention might have wanted to expose Loyalists and get affirmation from the voters of the new constitution, but there was no previous example to follow for adopting a state constitution. Virginia was the first to go through the independence process, and had no model to follow.

Proclaiming the constitution also eliminated any risk of the worst-case scenario, a rejection if advocates of independence had not turned out in adequate numbers to support the new form of government.

Thomas Jefferson criticized the claim that the Fifth Revolutionary Convention had the power to proclaim a constitution that later legislatures would not have the authority to modify. When delegates had been elected to that convention, voters had not anticipated it would write a constitution which future legislatures could not revise. In Notes on Virginia written in 1781, he advocated holding a special ratification vote to ensure the voters endorsed the new fundamental law because:1

The next constitution considered by Virginia voters was a document approved in the 1787 Constitutional Convention, held in Philadelphia, to replace the Articles of Confederation. To consider whether or not to ratify the proposed US Constitution, voters elected representatives in a special election to a special convention. Those Virginians who had the right to vote in 1788 did not approve the US Constitution directly, but instead through delegates they selected to make the decision.

There were 168 elected representatives at the Virginia Ratifying Convention - 85 Federalists, 80 Anti-Federalists, and 3 delegates who identified themselves as "neutral." They met in Richmond in the temporary capitol, since the new building for the legislature was still under construction, between June 2-25, 1788. Edmund Pendleton chaired the meeting.

Patrick Henry led the fight against ratification, supported by George Mason. He argued that the new national government would centralize power and limit the ability of Virginians to manage their society according to state priorities. That ideological argument relied upon theoretical risks, with opponents anticipating future problems.

Supporters of the new Federal government, led by James Madison, highlighted current problems with the national coalition of states managed under the Articles of Confederation. Decisionmaking was frozen by the voting requirements based on state delegations, though the Continental Congress had approved a mechanism for dealing with the Northwest Territory which Virginia had ceded to the national government.

The Continental Congress lacked the capacity to raise enough money from the 13 states to pay debts incurred during the American Revolution, and the national currency was "not worth a Continental." Leaders feared the states were on track to separate into separate blocks which would be influenced by Spain, England, and France. As seen by George Washington and others, a new mechanism of government was required to create a national union.

Both sides recognized the need to modify the draft produced in 1787 in Philadelphia. Opponents contended that revisions were required before ratification. Madison successfully argued that Virginia should ratify the document and then get the new US Congress to propose amendments.

Ratification by nine states was required before the new government would go into effect. Virginia was the largest state in size and population, so getting it to endorse a change in the form of national government was essential. Virginia became the 10th state to approve the US Constitution by a vote of 89-79; New Hampshire had ratified four days earlier.2

those qualified to vote in 1788 elected representatives to a special convention in 1788, where members decided to ratify the US Constitution in an 89-79 vote

Source: Mary Tucker Magill, History of Virginia for the Use of Schools (1873, p.238)

Starting in 1830, the pattern changed. Virginians voted directly on the adoption of new state constitutions that went into effect in 1830, 1851, 1864, 1870, and 1971. Not every ratification vote went as expected. One proposed new state constitution was rejected in 1862.

Even in 1864, after a convention organized by Governor Pierpont and the Restored Government of Virginia wrote a new state constitution, the document was approved by 500 voters. However, that election in the middle of the Civil War was basically window dressing. No opposing votes were recorded, and the tiny number of "yes" votes came from just a small slice of territory under the control of the Union-supported version of a state government.

The Clerk of the Virginia House of Delegates discounts the validity of the 1864 constitution, noting that it was drafted under wartime conditions and its legal status was never certain.3

Just once since 1776 did a convention proclaim a new constitution to be in force without approval by the voters. The 1902 Virginia constitution was declared to be in effect by the constitutional convention which wrote it. As in 1776, there was no ratification vote. The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals ruled in Taylor v. Commonwealth (1903) that the process of proclaiming the new constitution was sufficient since no one claimed to be governing under the previous constitution. The court determined that the new version adopted by the constitutional convention had gone into effect on July 10, 1902.4

The 1870 constitution created a process for amendments, requiring that they be submitted to the voters for approval. In 1926, Governor Harry F. Byrd created a new mechanism to revise the 1902 constitution. He had the General Assembly create a "Commission to Suggest Amendments to the Constitution."

That approach gave the Executive Branch more control over revising the constitution, rather than have the voters elect a special convention or have the legislators generate proposals through committees in the General Assembly. Governor Byrd fed his desires to a small commission filled with his supporters, and the General Assembly followed the commission's recommendations when it approved proposed amendments. Voters then approved the amendments, a validation process comparable to ratifying a new constitution created by a constitutional convention.

In 1945 and again in 1956, the voters authorized limited constitutional conventions to address one issue. In 1946, the issue was voting rights for people serving in the armed forces. in 1956, the issue was maintaining publicly-funded segregated schools. In both cases, the convention adopted revisions to the state constitution and proclaimed them to be in effect, without any ratification vote. Both revisions were politically popular, and proclaiming them to be in effect made the changes effective without delay.

In the 1960's, Governor Godwin mimicked the approach used by Governor Harry Byrd to maximize the influence of the Executive Branch in amending the state constitution. Godwin appointed the members of a Commission on Constitutional Revision, which was chaired by former Governor Albertis S. Harrison, Jr. The commission submitted recommendations to the General Assembly, and the legislature created six proposed amendments. Four of those were approved by a subsequent session of the General Assembly in 1970 and voters then approved all four.

The amendment process reduced the state constitution from 35,000 to 18,000 words. One major policy change was elimination of the pay-as-you-go limits on issuing state debt, which Byrd had incorporated in the amendments he orchestrated in 1926-28.5

The revisions to the state constitution which went into effect in 1971 eliminated the requirement that voters must approve calling a constitutional convention, and granted that power to the General Assembly. The amendments which went into effect in 1971 also established a new requirement that all future constitutions or amendments had to be submitted to the voters for approval. The amendments eliminated the potential, as demonstrated in 1776 and 1902, that a convention could totally rewrite/replace the state constitution without any public endorsement.

A convention, with limited or full authority, can no longer proclaim that the Virginia constitution has been changed. As desired from the beginning by Thomas Jefferson, ratification by the voters is now required. Jefferson wrote to James Madison in 1789, long before constitutions were venerated as vestiges of "founding fathers" and institutionalized as hard-to-revise documents, that each generation was entitled to choose how it should be governed. In Jefferson's words:6