Albemarle Barracks

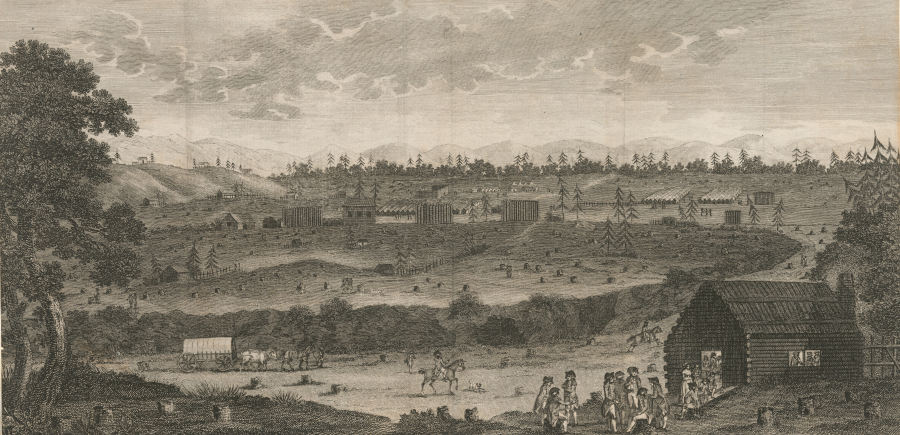

the Convention prisoners from the Battle of Saratoga were kept at the Albemarle Barracks between 1778-1781

Source: New York Public Library, Encampment of the Convention Army at Charlotte Ville in Virginia after they had surrendered to the Americans (1789)

General John Burgoyne surrendered his British Army to General Horatio Gates in October, 1777, after being defeated by the Americans at the Battle of Saratoga. The surrender terms negotiated between the two commanders, documented in the Convention of Saratoga, called for the 5,900 British and "Hessian" troops (from multiple areas within what is now modern Germany) to march to Boston. The Convention called for the prisoners to be shipped to England with a commitment not to rejoin the fight against the American rebels.

Though the British and Hessian troops marched to Boston, they were not sent across the Atlantic Ocean. George Washington feared that they would replace other soldiers, and those would be sent to America to fight the rebels. The Continental Congress found an technique to abrogate the Convention and keep the prisoners, though Burgoyne was allowed to return to England. Congress insisted that England had to ratify the surrender articles, and in January, 1778:1

- ...put a stop to any embarkation, till the convention is ratified at home by the King and Parliament; an event that can never happen; as it would be allowing the authority of the Congress, and the independence of the Americans

The British paid the Convention Army's bills, but the blockade of Boston Harbor by British ships made it difficult to provide supplies to the prisoners. The British part of the Covention Army was moved from Cambridge to Rutland, Vermont. On October 16, 1778 the Continental Congress decided that both the British and the Hessians (still at Cambridge) would be sent to Charlottesville.

The Americans claimed the move to Virginia was necessary because supplies would be more available there. Starting in November the 4,000 common soldiers walked 15 or more miles each day, then camped by the side of the road each night. Officers rode horses, traveling further each evening to find a house in which they could sleep. The officers paid for the hospitality, noting that their gold/silver specie was welcome everywhere but state currency had value only within the boundaries of that state.

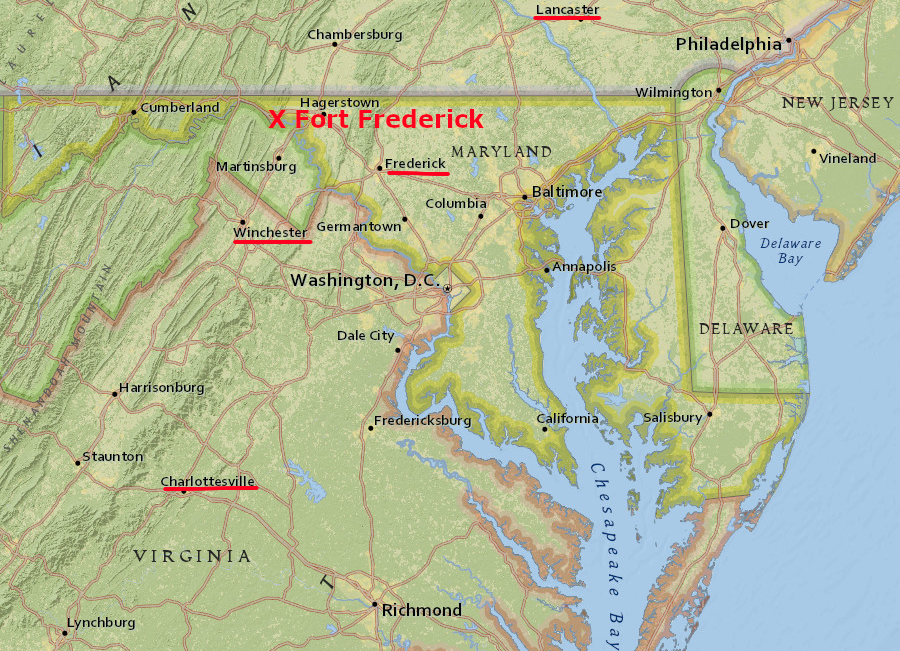

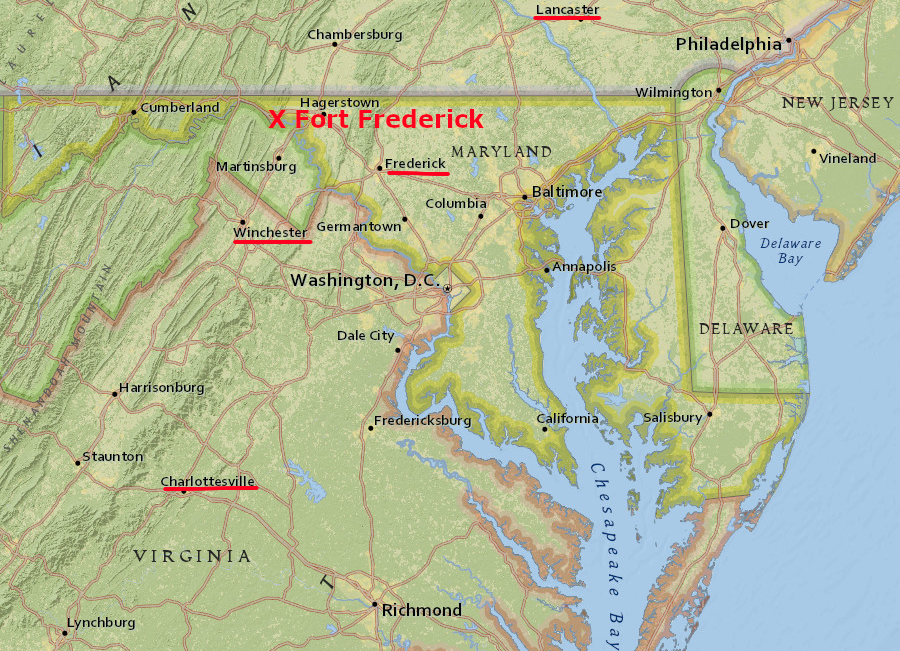

The weather was mild for the entire march to Charlottesville for the first brigades, but a major snowstorm struck when the third brigade reached Frederick, Maryland. One woman in Pennsylvania had commented earlier that God must have become a Tory, to provide such good conditions.

British officers assumed a wintertime march of 600 miles was designed in part to make it possible for deserters to leave the army and become laborers on American farms. The Hessian soldiers in particular were willing to desert in order to live free among other German-speaking settlers in Pennsylvania, rather than complete the march and be trapped in a prisoner-of-war camp for an undetermined length of time.2

The troops entered Virginia after a trip across the ice-filled Potomac River at Noland's Ferry downstream from Point of Rocks.

About 2,000 British soldiers, 1,900 German soldiers, and 300 women and children passed through Leesburg, then along the old Native American trail east of the Blue Ridge. When they arrived in January 1779, there was snow on the ground.

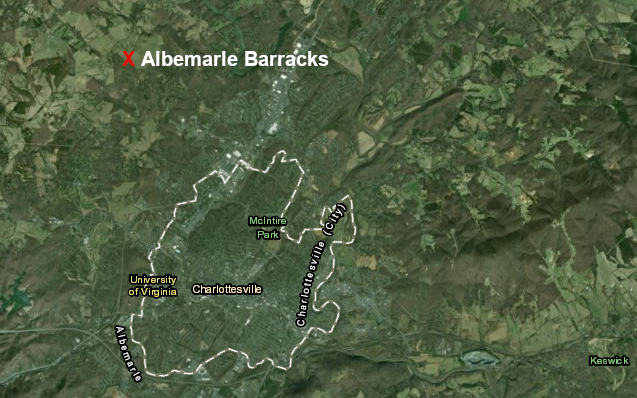

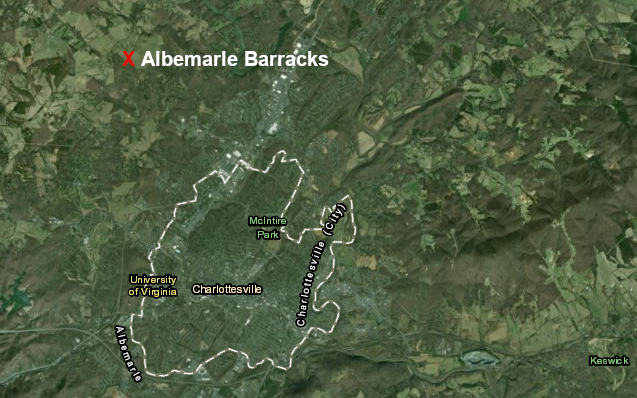

the Albemarle Barracks were built five miles northwest of the town of Charlottesville in 1779

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The prisoners were sent to a site on Ivy Creek five miles from Charlottesville. Their new home was on land made available by Colonel John Harvie, a member of the Continental Congress.

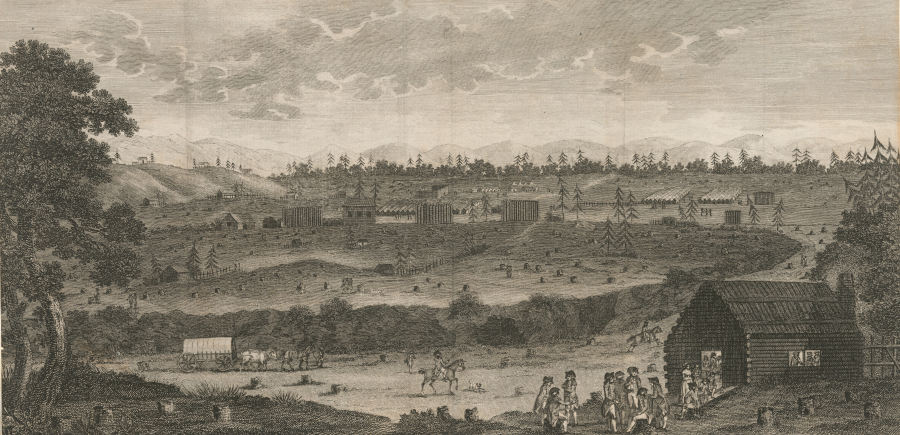

Despite directions from the Continental Congress to prepare facilities by mid-December, Charlottesville did not have housing ready for the prisoners. The barracks prepared by the Virginians were about 300 log huts, each 24' long by 14' wide and intended to hold about 18 men. A "main street" divided the barracks intended for the British from those for the Hessians.

The structures were built without nails and had no roofs when the Convention soldiers arrived. As described by a Hessian officer:3

- The barracks are built in four rows in a square, each row consisting of 12 barracks. There are seven of these squares one after another, which makes altogether 336 barracks 36 of which in the quarters of the German troops, were not intended to be built. The 12 barracks in each row are close together without space between. Each barrack is 24 feet long, and 14 feet wide, big enough to shelter 18 men.

- The construction is so miserable that it surpasses all that you can imagine in Germany of a very poorly built log house. It is something like the following:

- Each side is put up of 8 to 9 round fir trees, which are laid one on top the other, but so far apart that it is almost possible for a man to crawl through. At the ends where they join, they are indented, thus keeping them in place. The roof is made of round trees covered with split fir trees, intended to take the place of boards. These trees, most the time only one hand wide, make bad roofing, and the rain comes through everywhere...

- ...There is not a single nail in the whole lot of barracks, except 5 or 6 in the doors. Everything is just put together without nails. Windows are superfluous, fresh air, rain having free passage. No chimney is needed for the same reason, and the fire is made in the middle of the floor.

A British officer in the third brigade noted upon arrival that the officers who had arrived earlier already had occupied the available spaces in Charlottesville's private houses. Later arrivals had to scour the countryside to find people willing to provide shelter. Paroles allowed officers to travel as far as Richmond.

Military discipline weakened when the march ended. Some officers found supplies of what one identified as an "abominable liquor, called peach brandy," and a half-dozen duels were fought over perceived slights to personal honor. Late-arriving officers discovered:4

...not a drop of any kind of spirit, what little there had been, was already consumed by the first and second brigade; many officers, to comfort themselves, put red pepper into water, to drink by way of cordial.

While officers searched for beds in warm houses and struggled over status, the common soldiers experienced a much rougher situation upon arrival:5

- after the hard shifts they had experienced in their march from the Potowmack, they were, instead of comfortable barracks, conducted into a wood, where a few log huts were just begun to be built, the most part not covered over, and all of them full of snow ; these the men were obliged to clear out, and cover over to secure themselves from the inclemency of the weather as quick as they could, and in the course of two or three days rendered them a habitable, but by no means a comfortable retirement; what added greatly to the distresses of the men, was the want of provisions, as none had as yet arrived for the troops...

The soldiers quickly improved the barracks for shelter and created gardens that impressed the local community. Modern-day Barracks Road and a shopping center mark the path from the town of Charlottesville to the location where the Convention soldiers were kept.

barracks at the Valley Forge encampment suggest how the Convention Army prisoners lived near Charlottesville in 1779-1781

Source: National Park Service, The Encampment

Colonel James Wood and Colonel Theodorick Bland gave the British and German officers authority to live within 20 miles of Charlottesville, and they rented space in private housing around the town. Thomas Jefferson saw the prisoners as an economic stimulus to the local economy, and the officers as an intellectual stimulus for him. He played violin with the Hessian commander Baron Frederick von Riedesel at Monticello, while the commander's wife led dances.

Baron Friedrich Adolf Riedesel rented Colle, a house built by Philip Mazzei, but ultimately built his own house because Colle was an unstable structure. The English commander, Brigadier General William Phillips, lived at Blenheim. He tried to build another house, but the agent he sent to convert specie into American dollars bought counterfeit money produced by the British to undercut the rebel war effort.

General Phillips and Riedesel were treated more as guests than as prisoners. They were even allowed to travel to the Berkeley Springs health resort.

During the next 18 months, some officers were formally exchanged for American prisoners. Baron Frederick Adolf Riedesel and General William Phillips were exchanged for General Benjamin Lincoln, who had surrendered at Charleston when the British captured hat city in 1780.

Some of the Saratoga troops deserted to the Americans, especially when food supplies ran low because the British quit paying the bills after the troops were sent to Virginia. Others apparently managed to escape and travel all the way back to the British base at New York City.6

Revenue generated by the need to feed and supply the British and Hessian troops provided an economic boost for Albemarle County. When Thomas Jefferson heard in 1779 that the Continental Congress was concerned about treatment of the Convention prisoners and the Virginia governor was considering moving them, he wrote to Governor Patrick Henry. Jefferson noted that the barracks could have been located closer to the Rivanna River and grain brought to that site from mills along the James River. However, placing the prisoners in central Virginia near Charlottesville was better than the alternatives.

Jefferson challenged claims that relocation was the best way to reduce costs and improve conditions for the prisoners at Albemarle Barracks. He suggested that reforming wasteful procedures of the commissaries responsible for providing supplies was a better opportunity:7

- All the grain made in the counties adjacent to any kind of navigation may be brought by water to within 12 miles of the spot. For these 12 miles waggons must be employed, I suppose half a dozen will be a plenty. Perhaps this part of the expence might have been saved had the barracks been built on the water.

- But it is not sufficient to justify their being abandoned now they are built and waggonage indeed seems to the commissariate an article not worth œconomising. For they kill meat at Richmond, Fredsbgh and I suppose at other places and waggon it to the barracks instead of driving it alive, but when they purchase flour in the upper counties they contrive a wanton and studied circuity of waggonage. To mention only one fact, they have bought quantities of flour for these troops in Cumberland, have ordered it to be waggoned down to Manchester and waggoned thence to the Barracks...

- When I said that the grain might be brought hither from all the counties of the state adjacent to navigation, I did not mean to say it would be proper to bring it from all of them. On the contrary I think commissary should be instructed after the next harvest not to send one bushel of grain to the barracks from below the falls of the rivers or from the Northern counties.

- The counties on tide waters are accessible to the calls for our own army. Their supplies ought therefore to be husbanded for them. The counties in the Northern parts of the state are not only within reach for our own Grand army but peculiarly necessary for the support of Mackintosh’s army, or for the support of any other western expedition that the uncertain conduct of the Indians should render necessary.>/dd>

Jefferson also highlighted the military advantage of being in central Virginia. Ay British rescue attempt would require marching for about 90 miles from where ships could unload troops near the Fall Line to reach Charlottesville:8

- The safe custody of these troops is another circumstance worthy consideration. Equally removed from the access of an Eastern or Western enemy central to the whole state so that should they attempt an eruption in any direction they must pass through a great extent of hostile country, in a neighborhood thickly inhabited by a robust and hardy people zealous in the American cause, acquainted with the use of arms and the defiles and passes by which they must issue, it should seem that in this point of view no place could have been better chosen.

Charlottesville was far enough inland to be safe from sea raids, but in October 1780 General Clinton sent General Alexander Leslie to establish a post in Hampton Roads. He initially landed at Hampton, then moved to Portsmouth on the Elizabeth River. A British raiding party in Hampton Roads was intended to create a diversion for Lord Cornwallis' operations in the Carolina backcountry. The governor of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson, feared the prisoners in Charlottesville would try to escape and join Leslie or the British might move inland to recover them.

Despite the economic impacts to the Albemarle County area, Jefferson ordered that the prisoners be taken to Fort Frederick in Maryland. The British left on November 20, 1780, marching through Rockfish Gap to reach the road north via the Shenandoah Valley. The British prisoners set fire to their huts when leaving. The "main street" gap between the British and Hessian barracks prevented the Hessian huts from catching fire.

The 1,500 Hessians were kept in Charlottesville area until February 1781, when they were sent to Winchester. Virginia officials calculated that the Germans were less likely to escape in order to reach General Leslie or other British forces that might occupy Hampton Roads.

Governor Jefferson notified George Washington about splitting the British as Hessian prisoners. Under the Saratoga Convention, officers had to be kept with the soldiers. Jefferson interpreted the convention to authorize dividing the British from the Hessians, but made sure Washington was prepared to respond if the British complained and used the decision to interrupt the exchange of officers:9

- The want of Barracks at fort Frederic as represented by Colo. Wood, the difficulty of getting waggons sufficient to move the whole convention troops at once, and the state of unreadiness in which the regiment of guards is, have induced us to think that it will be better to remove those troops in two divisions, and as the whole danger of desertion to the enemy & of correspondence with the disaffected in our southern counties is from the british only (for from the Germans we have no apprehensions on either head) we have advised Colo. Wood to move on the british in the first division and to leave the Germans in their present situation to form a second division and to be moved so soon as barracks may be erected at Fort Frederic...

- I cannot suppose that this will be deemed such a seperation as is provided against by the convention, nor that their officers will wish to have the whole troops crouded together into barracks which probably are not sufficient for half of them...

When Col. Banastre Tarleton raided Charlottesville in June, 1781 in an attempt to capture the General Assembly and Thomas Jefferson, about 20 of the Hessian prisoners of war were able to gain their freedom. They had not been kept in the Albemarle Barracks and sent to Winchester; instead, they had been working for Virginia farmers in the countryside.

Tarleton wrote in his memoirs:10

- ...the Britifs were joined by about twenty men, who being soldiers of the Saratoga army, had been dispersed throughout the district, and allowed to work in the vicinity of the barracks, where they had been originally imprisoned. Many more would probably have joined their countrymen, if Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton had been at liberty to remain at Charlottesville a few days.

the Convention prisoners from the Battle of Saratoga were kept at the Albemarle Barracks between 1778-1781

Source: New York Public Library, Encampment of the Convention Army at Charlotte Ville in Virginia after they had surrendered to the Americans

Maryland Governor Thomas Sim Lee had no desire to receive the British prisoners sent by Jefferson, fearing the British might target his state. He also had no housing available at Fort Frederick. The Continental Congress ordered Maryland to accept them, however. They were placed in local homes, taverns, and even the poorhouse.

Later, Congress sent the British prisoners and then the Hessians to Pennsylvania. The Hessians were placed in a camp near Reading, and the British were sent to Camp Security near York. In September, 1781, the British officers were marched to East Windsor in Connecticut.11

After the Albemarle Barracks were abandoned, the Continental Army's quartermaster general planned to sell the buildings. The assistant quartermaster general for Virginia assessed that they had minimal value, and John Harvie got his land back without valuable improvements:12

- Agreeable to your instructions I have made as exact inspection of the barracks and other public buildings at this place as seems to be required, & do report that all the ranges that were built for the use of the Convention Army cannot be considered in any other light than a pile of ruins, more than one third of them were burnt by the prisoners at the time they were ordered to Maryland, & the doors & windows of the others, I believe, almost without one exception, pulled to pieces & destroyed for the few nails that were in them.

- The taking off the facings from the doors & windows, which before confined the logs, has occasioned the huts in some instances, to tumble down, & in others to be greatly racked from their original shape. What plank was in them for floors or births [sic] has been entirely taken away; their covers are also, speaking generally, quite dismantled, the slabs that were on them being chiefly consumed or carried off by the Country people who seemed to consider every think [sic] of this kind, when the troops were removed, as free plunder...

Links

- AmRev-Hessians

- Walking the Berkshires

References

1. Thomas Anburey, Travels Through the Interior Parts of America: In a Series of Letters, Volume 2, 1789, p.84, https://books.google.com/books?id=ymwFAAAAQAAJ (last checked June 10, 2019)

2. Thomas Anburey, Travels Through the Interior Parts of America: In a Series of Letters, Volume 2, 1789, pp.228-229, pp.254-255, p.273, pp.308-311, p.316, https://books.google.com/books?id=ymwFAAAAQAAJ; William W. Reynolds, "Demise of the Albemarle Barracks: A Report to the Quartermaster General," Journal of the American Revolution, May 31, 2018, https://allthingsliberty.com/2018/05/demise-of-the-albemarle-barracks-a-report-to-the-quartermaster-general/ (last checked April 26, 2025)

3. "Gentleman Johnny's Wandering Army," American Heritage, December 1972, https://www.americanheritage.com/content/gentleman-johnny%E2%80%99s-wandering-army; "All About Albemarle Barracks," Charlottesville Solutions, https://www.charlottesvillesolutions.com/2017/04/all-about-albemarle-barracks/; "Journal of Du Roi the Elder," German American Annals, German American Historical Society, Volume IX, Numbers 3 and 4 (1911), p.201, pp.206-207, https://books.google.com/books?id=frEVAAAAYAAJ (last checked June 5, 2018)

4. Thomas Anburey, Travels Through the Interior Parts of America: In a Series of Letters, Volume 2, 1789, pp.319-320, https://books.google.com/books?id=ymwFAAAAQAAJ (last checked June 10, 2019)

5. Thomas Anburey, Travels Through the Interior Parts of America: In a Series of Letters, Volume 2, 1789, pp.317-318, https://books.google.com/books?id=ymwFAAAAQAAJ (last checked June 10, 2019)

6. Charles Ramsdell Lingley, "The Treatment of Burgoyne's Troops Under The Saratoga Convention," Political Science Quarterly, Volume 22, Number 3 (September, 1907), http://www.jstor.org/stable/2141057; "Mr. Jefferson's POW Camp," Frances Hunter's American Heroes Blog, https://franceshunter.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/mr-jeffersons-pow-camp/; "Gentleman Johnny's Wandering Army," American Heritage, December 1972, https://www.americanheritage.com/content/gentleman-johnny%E2%80%99s-wandering-army; "The winners write history. What happens to the losers?" The Historical Dilettante, http://historicaldilettante.blogspot.com/2012/07/the-winners-write-history-what-happens.html (last checked June 5, 2018)

7. "From Thomas Jefferson to Patrick Henry, 27 March 1779," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-02-02-0092 (last checked April 26, 2025)

8. “From Thomas Jefferson to Patrick Henry, 27 March 1779,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-02-02-0092 (last checked April 26, 2025)

9. Michael Cecere, The Invasion of Virginia 1781, Westholme Publishing, 2017, p.10, https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Invasion_of_Virginia_1781.html?id=SgJLvgAACAAJ; "The winners write history. What happens to the losers?" The Historical Dilettante, http://historicaldilettante.blogspot.com/2012/07/the-winners-write-history-what-happens.html; "To George Washington from Thomas Jefferson, 3 November 1780," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-29-02-0052 (last checked April 26, 2025)

10. Lieutenant-General Banastre Tarleton, A history of the campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the southern provinces, Printed for Colles (Dublin), 1787, p.305, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/yale.39002002440338 (last checked May 6, 2020)

11. "How Revolutionary Soldiers Came to be Housed in the Poorhouse at Frederick, Maryland," The Poorhouse Story, http://www.poorhousestory.com/MD_Frederick_POWstory.htm; "How Many Revolutionary War Prisoners Were at York's Camp Security?" Universal York, http://www.yorkblog.com/universal/2008/07/22/how-many-revolutionary-war-pri/; "Gentleman Johnny's Wandering Army," American Heritage, December 1972, https://www.americanheritage.com/content/gentleman-johnny%E2%80%99s-wandering-army (last checked June 5, 2018)

12. William W. Reynolds, "Demise Of The Albemarle Barracks: A Report To The Quartermaster General," Journal of the American Revolution, https://allthingsliberty.com/2018/05/demise-of-the-albemarle-barracks-a-report-to-the-quartermaster-general/ (last checked April 26, 2025)

The Military in Virginia

Virginia Places