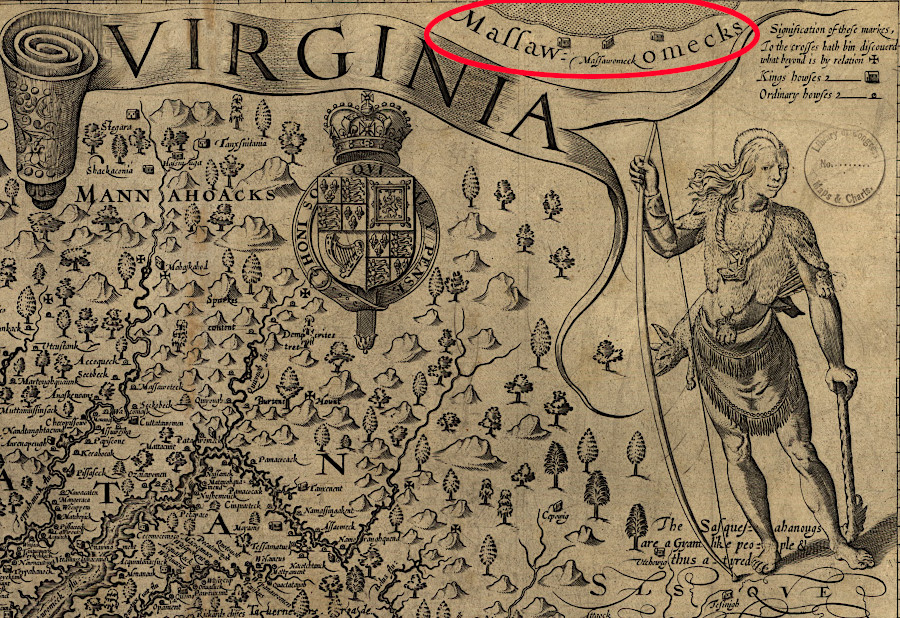

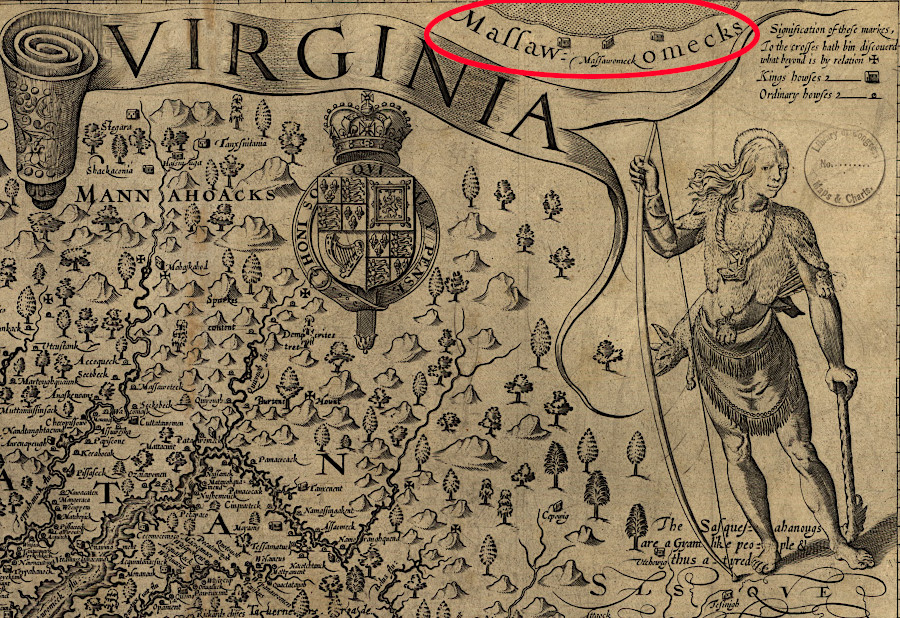

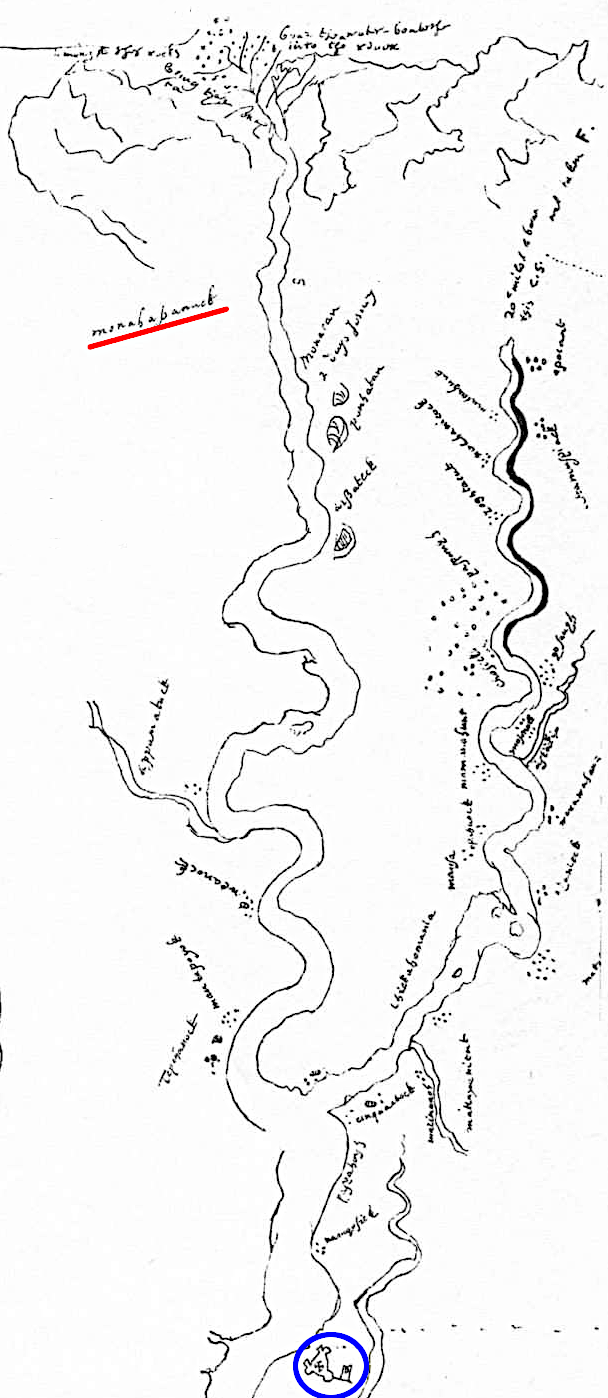

Massawomeck in Virginia

John Smith was told in 1608 that the Massawomeck lived upon a great salt water

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

John Smith was the first English colonist to learn about the Massawomeck. Powhatan spoke about them in December 1607, when Smith was a captive before being "rescued" by Pocahontas. Smith was quizzing Powhatan regarding the lands and peoples to the west, with a special interest in reports of a salt sea (Pacific Ocean). Powhatan apparently was straightforward when sharing his description of the Massawomeck.

Smith claimed when Powhatan answered his inquiries about the salt sea, he identified the people living there as cannibals. They came east on raids, threatening the Piscataway who lived at Moyaone and also the Patawomeck who lived at Marlboro Point near Aquia Creek. In 1608, Smith identified the cannibals as the "Pocoughtronack:"1

- Hee described also vpon the same Sea, a mighty Nation called Pocoughtronack, a fierce Nation that did eate men, and warred with the people of Moyaoncer and Pataromerke, Nations vpon the toppe of the heade of the Bay, vnder his territories: where the yeare before they had slain an hundred. He signified their crownes were shauen, long haire in the necke, tied on a knot, Swords like Pollaxes.

By the time Smith published his map of Virginia in 1624, he labeled the nation living northwest of the Chesapeake Bay as the Massawomeck.2

On their expeditions to the Chesapeake Bay, the Massawomeck constructed canoes from bark sealed watertight with tree resin. Bark canoes could be assembled quickly compared to the Algonquian technique of burning and scraping a tree trunk. One anthropologist has suggested that the "Massa" component of the tribe's name was a word referencing "canoe." The name of he tribe may have meant "those who come and go by boat."

John Smith personally met a group of Massawomecks who were paddling canoes on the Chesapeake Bay. Trading with them for food and bearskins required using signs; the English did not understand their Iroquoian language. Smith concluded from their boats that they lived on a large lake or even the edge of the South Sea (Pacific Ocean):3

- Seaven boats full of these Massawomekes wee encountred at the head of the Bay; whose Targets, Baskets, Swords, Tobaccopipes, Platters, Bowes, and Arrowes, and every thing shewed, they much exceeded them of our parts, and their dexteritie in their small boats, made of the barkes of trees, sowed with barke and well luted with gumme, argueth that they are seated vpon some great water.

Tribes under the control of Powhatan on the southern half of the Chesapeake Bay feared attack by the Massawomeck, indicating the boats were capable of traveling long distances. When Smith sailed up the Chesapeake Bay for the second time in July 24-September 7, 1608, he discovered the local residents built palisades around their towns to protect against attacks by the Massawomecks:4

- Beyond the mountaines from whence is the head of the river Patawomeke, the Salvages report inhabit their most mortall enemies, the Massawomckes, vpon a great salt water, which by all likelihood is either some part of Cannada, some great lake, or some inlet of some sea that falleth into the South sea. These Massawomekes are a great nation and very populous. For the heads of all those rivers, especially the Pattawomekes, the Pautuxuntes, the Sasquesahanocks, the Tockwoughes are continually tormented by them: of whose crueltie, they generally complained, and very importunate they were with me, and my company to free them from these tormentors...

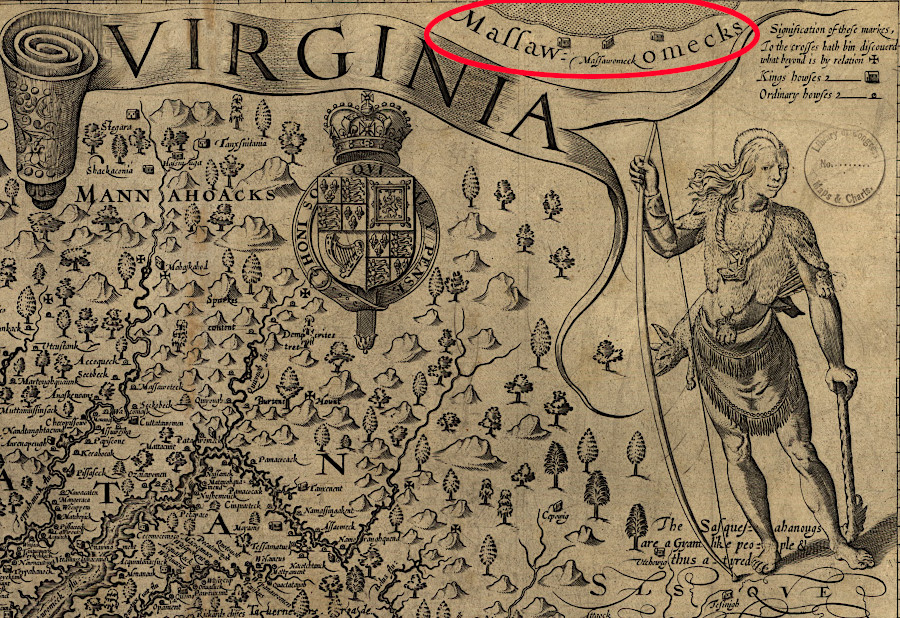

a sketch that John Smith may have sent to England in 1608 identified where the Massawomeck lived northwest of Jamestown (blue circle)

Source: she-philosopher.com, The “Zuñiga Chart” of Virginia, 1608

When Smith met the Massawomecks during his second journey in 1608, he was moving from the mouth of the Patapsco River to the eastern side of the bay. The Massawomecks had recently raided a town of the Tockwogh on the Sassafras River. Weapons used during their attack included hatchets obtained from the French on the St. Lawrence River.

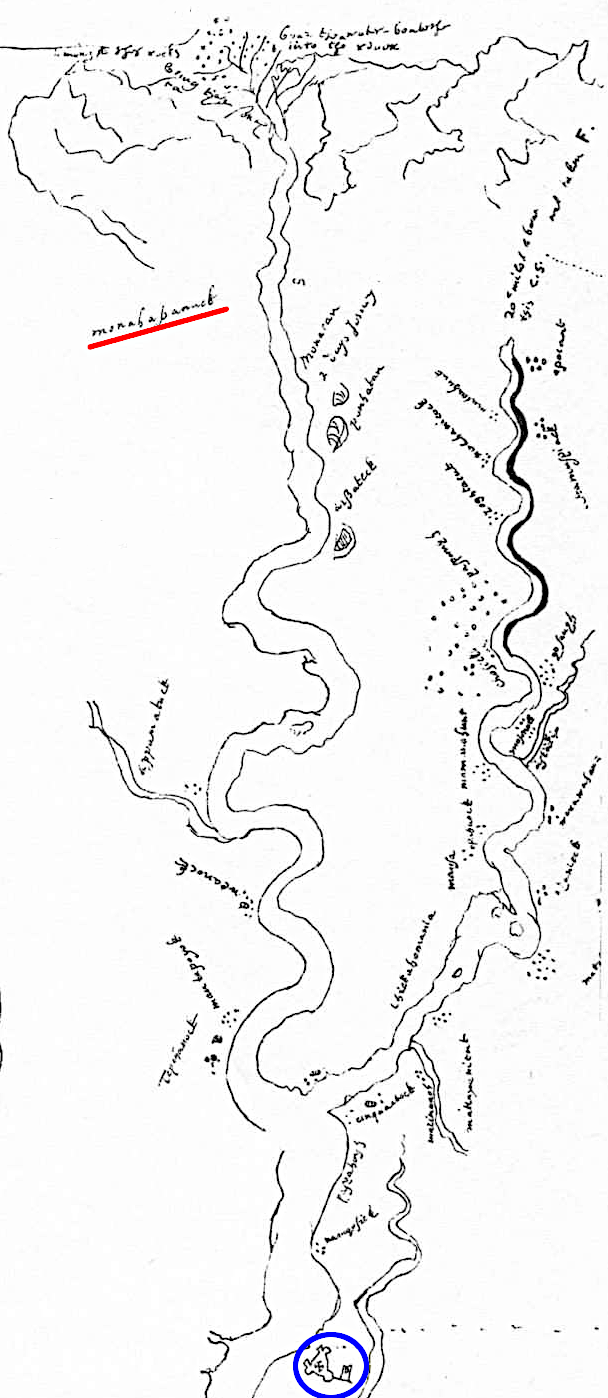

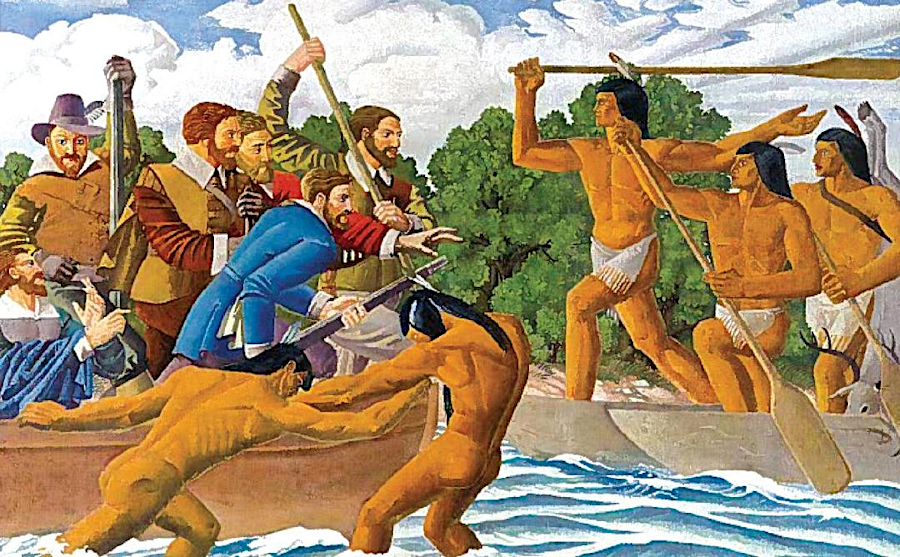

one mural painted in the Arlington Post Office during the Great Depression depicts John Smith meeting the Massawomecks

Source: Arlington Historical Society, Arlington Post Office (Auriel Bessemer, 1938)

Smith then sailed to the Tockwogh town. That Algonquian-speaking group saw on his shallop shields and other items that he had obtained from the Massawomeck. The Tockwogh assumed he was allied with the raiding party; they were hostile to the English until Smith convinced them that he had obtained the Massawomeck goods in a fight. Making friends with the Tockwogh led to a meeting with their allies, the Susquehannocks. The Susquehannocks promised gifts to Smith if would stay and help defend them against the Massawomeck.

Smith's second journey up the Chesapeake Bay also included a stop in the Rappahannock River. His initial encounter with the Rappahannocks was hostile, and the English used the shields of the Massawomecks to protect themselves against 1,000 arrows fired at them from the shore. The shields, which the Massawomecks probably carried on their long walk to the Chesapeake Bay, were light but effective. They were:5

- ...made of little small sticks woven betwixt strings of their hempe and silke grasse, as is our Cloth, but so firmely that no arrow can possibly pierce them.

Smith promised the Susquehannocks and other tribes that he would return and assist them, but that was a promise he could not keep personally. By October 1609, Smith was on a boat sailing back to England. He had run into great resistance as he attempted to lead the colony as President of the Council in 1609. His time in Virginia ended after he was wounded in what may have been an assassination attempt, when his gunpowder pouch caught fire while he was asleep on a boat returning to Jamestown.6

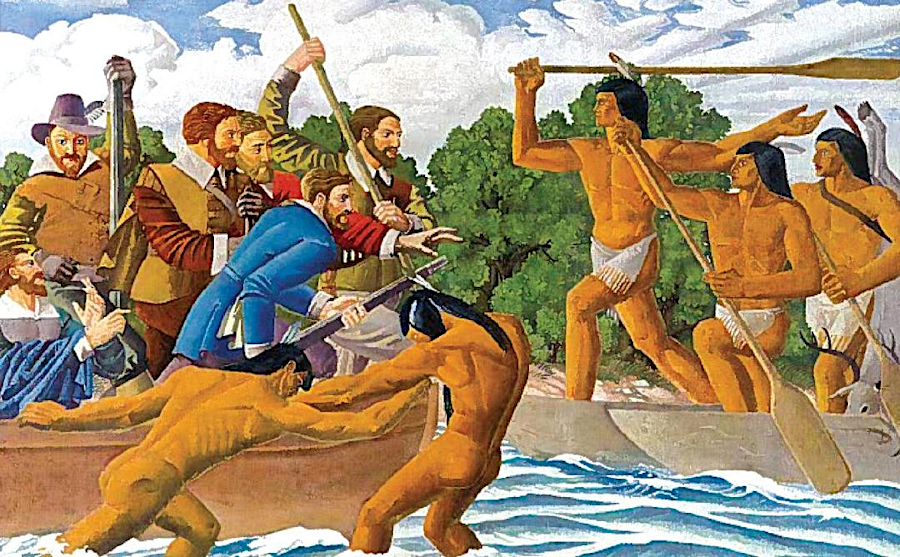

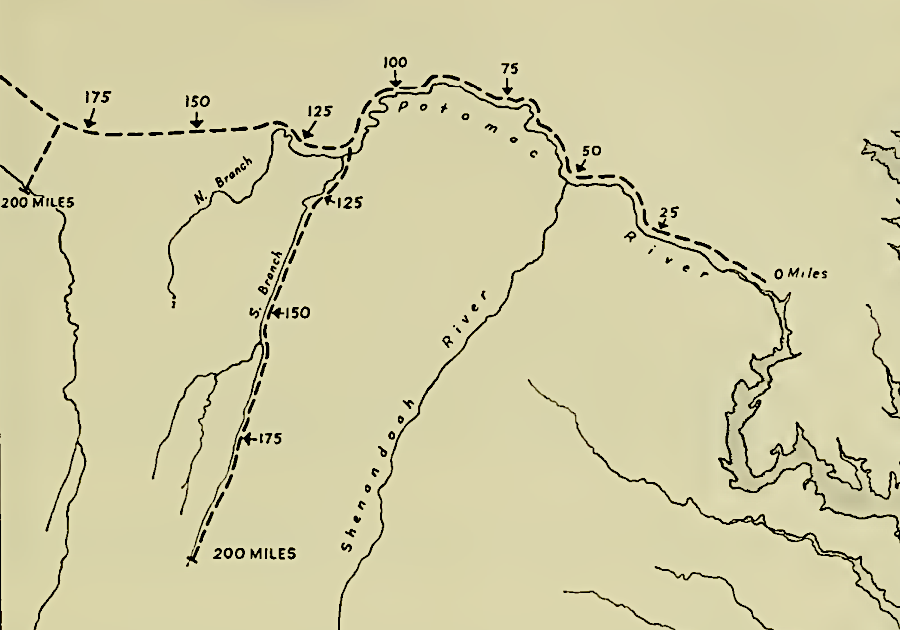

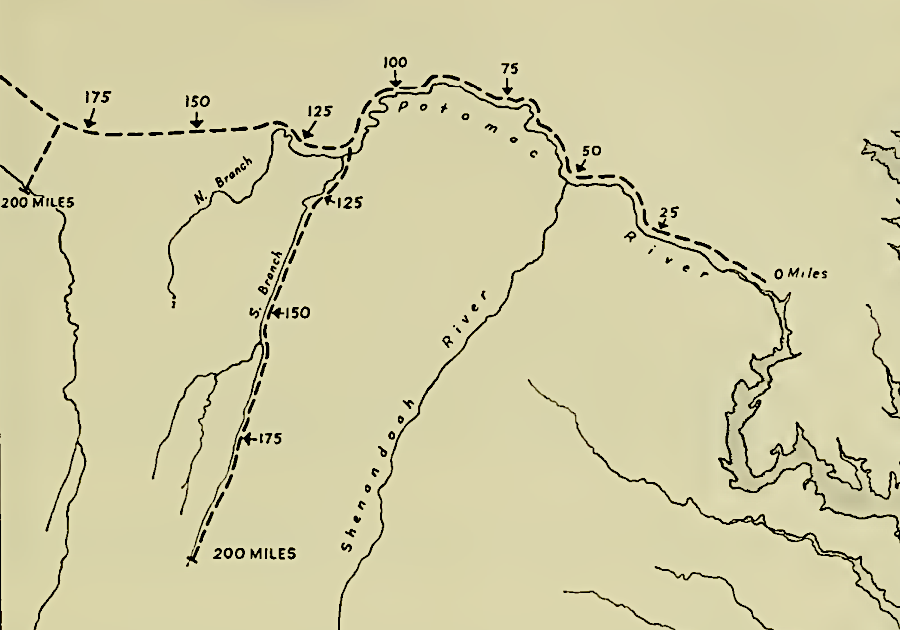

the Massawomeck who raided tribes along the Potomac River lived northwest of the Chesapeake Bay, closer to the St. Lawrence River ("Canada flu")

Source: John Carter Brown Library, A mapp of Virginia discouered to ye Falls, and in it's Latt: From 35 deg: & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg: bounds of new England (by John Farrer in 1651)

Smith's 1624 map placed the Massawomecks north of the 40th degree of latitude and near a speculated lake or the South Sea (Pacific Ocean). His interpretation of Powhatan's information could have been wildly incorrect if he was drawing "a great turning of Salt Water" just 4-5 days from the Fall Line. His map also could be eerily accurate, if Lake Erie was the body of water.

Ancestors of the Massawomecks occupied the Ohio River Valley and the Allegheny Plateau of southwestern Pennsylvania starting around 1100 CE (Common Era). They established what archeologists describe as the Monongahela culture, similar to the Fort Ancient people to the south and equivalent to the Luray culture in the Shenandoah Valley. Starting in the 1400's, the Monongahela cultural ties shifted from Fort Ancient groups in the middle Ohio River valley and connections increased with Iroquoian groups in the Susquehanna and St. Lawrence watersheds.

Based upon the absence/presence of European trade goods at archeological sites, the Luray culture almost completely disappeared by 1575 but the Monongahela culture lasted until 1635. The longer survival time might reflect greater distance way from the path traveled by Haudenosaunee, Catawba, and Cherokee raiders along the Blue Ridge.

In the 1500's Susquehannocks may have migrated into the watersheds of the North Branch and South Branch of the Potomac River. They would have integrated with the Keyser culture people already living there. The expansion or relocation of Massawomeck territory could have increased their control of the Chesapeake Bay whelk shell trade with the Neutrals, Petun and other groups living south of the Great Lakes. The whelk trade route was later used for trading furs with Europeans on the Potomac River/Chesapeake Bay.

At the start of the 1600's, some Massawomecks apparently moved from the upper reaches of the Ohio River to occupy the headwaters of the Potomac River. A major drought in 1587-89, and another in 1607-1612, might have been the primary factors in the relocation. Avoiding raids by the Haudenosaunee to obtain captives, which were desired to repopulate towns decimated by disease, were another reason to move further south.

The Massawomecks displaced the Susquehannocks living in the Upper Potomac River watershed by 1630. However, by that time their ability to remain there as an intact tribe was short-lived. As the European colonists expanded their range, the "shatter zone" of disrupted culture rapidly expanded westward.7

The Massawomecks appear to have been culturally similar to the Susquehannocks to their east and the Erie (Atiouandaron) to the west, all speaking Iroquoian languages. The Huron to the north also spoke an Iroquoian-based language but with a different dialect; the Hurons said the Massawomecks were "people who talk funny." Algonquian speakers referred to all Iroquoian speakers as "Mingos."8

Henry Spelman saw a fight between the "Patomeck and the Masomeck" while he was living with the Patawomeck in 1609-10:9

- Beinge in the cuntry of the Patomecke the peopel of Masomeck weare brought thether in Canoes which is a kind of Boate they have made in the forme of an Hoggs trowgh But sumwhat more hollowed in, On Both sids they scatter them selves sum litle distant one from the other, then take they ther bowes and arrows and havinge made ridie to shoot they softly steale toward ther enimies, Sumtime squattinge doune and priing if they can spie any to shoot at whom if at any time he so Hurteth that he can not flee they make hast to him to knock him on the heade, And they that kill most of ther enimies are heald the cheafest men amonge them; Drums and Trumpetts they have none, but when they will gather themselves togither they have a kind of Howlinge or Howbabub so differinge in sounde one from the other as both part may very aesly be distinguished. Ther was no greater slawter of nether side But ye massomecks having shott away most of the arrows and wantinge Vitall [was] weare glad to retier...

Henry Fleet learned more about the Massawomecks in 1632. He had been trading corn and other products between Massachusetts and Virginia, and along the Chesapeake Bay. Various groups of Native Americans all desired to trade for hatchets, knives, and clothing (coats and shirts) that had been manufactured in England ("truck").

Fleet had a particular familiarity with the Anacostans who lived at the site of modern Washington, DC. He had been captured there during a trading expedition in 1623 in which Henry Spelman was killed, and was not released until 1627.

Fleet went up the Potomac River seeking beaver skins and reached the town of the Anacostans in June, 1632. He discovered they were hostile to the Piscataways and their tayac ("emperor"). The Anacostans were the middlemen between the Massawomecks and the English, controlling the trade with the tribes upstream along the Potomac River.

Because Fleet dealt with Anacostans and Massawomecks in 1632, and did not but furs from the Susquehannocks, it appears that tribe had been excluded from trade in the upper Potomac River Valley. The Massawomecks were powerful enough to come east to the Fall Line and protect the Anacostans against the Piscataway tayac ("emperor") living on the Coastal Plain:10

- There is but little friendship between the Emperor and the Nacostines, he being fearful to punish them, because they are protected by the Massomacks or Cannyda Indians, who

have used to convey all such English truck as cometh into this river to the Massomacks.

The Anacostans wanted to retain control of the trade and block the English from negotiating directly with the Massawomecks. Despite their objections, Fleet was willing to risk irritating them. He managed to send his brother with two "trusty Indians" beyond the Fall Line to meet directly with the tribes upstream.

Based on the time traveled ("seven days going, and five days coming back") and assuming Fleet's brother traveled 20-28 miles per day, the party went about 100-140 miles upstream. Fleet's brother was west of the Blue Ridge in what is now western Maryland, western Pennsylvania, or West Virginia. He may have reached the Youghiogheny River, a tributary of the Monongahela River upstream of modern Pittsburgh.

"

Fleet wrote in his journal that his brother had visited thirty villages. The Massawomecks had four major towns:11

- I find the Indians of that populous place are governed by four kings, whose towns are of several names, Tonhoga, Mosticum, Shaunetowa, and Usserahak, reported above thirty thousand persons, and that they have palisades about their towns made with great trees, and with scaffolds upon the walls....

- ...in one palisado, and that being the last of thirty, there were three hundred houses, and in every house forty skins at least, in budles and piles.

Henry Fleet's brother traveled 100-140 miles beyond the Fall Line in 1631 to meet the Massawomecks

The Massawomeck nation may have been composed of four allied tribes. The actual location of the four large Massawomeck towns is unknown. Archeological traces of their culture, and supposedly 30 towns with an average of 1,000 people each, are thin. The reported size of the Massawomeck population may have been enlarged by including the Erie and perhaps other Iroquois-speaking groups who lived west of the Seneca, but they were not part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.12

Archeologists associate the Massawomeck with the Monongahela culture. Matching archeological evidence with historical resources:13

- It is likely that between 1620 and 1640, Monongahela peoples expanded their range into the Potomac Valley to exploit resources formerly utilized by the Susquehannocks. This critical period was also a time of population decimation by disease, a factor that may have played a significant role in regional population shifts. The Monongahela peoples of the Appalachian Plateau region were believed to have been dispersed by the Seneca around 1635 at a time when Ohio Valley trade networks were disrupted.

Massawomecks came downstream to Fleet's ship at the Fall Line with 60 canoes loaded with furs, but were intercepted by the Anacostans and unable to trade directly. Fleet reported that the first group he met included a woman and an interpreter. The Massawomeck traders:14

- ...came from a town called Usserahak, where were seven thousand Indians.

A day later a separate group arrived to deal with Fleet. They said they were from the town of Mosticum. The Massawomecks said the seven men actually lived three days away from that town and were a separate group called "Hereckeenes." The Hereckeenes traveled 15 days through the forests of what became Pennsylvania and New York to trade at Quebec on the St. Lawrence River.

As described by Fleet:15

- ...there came from another place seven lusty men with strange attire; they had red fringe, and two of them had beaver coats... Their language was haughty and they seemed to ask me what I did there, and demanded to see my truck, which upon view, they scorned. They had two axes such as Captain Kirk traded in Cannida, which he bought at Whits of Wapping [in England], and there I bought mine, and think I had as good as he.

One of Fleet's men joined the Hereckeenes to travel to their home. The Massawomeck from Usserahak warned Fleet that the group would kill and eat him, and the Anacostans soon reported that three days after leaving Great Falls Fleet's man had been killed.

The Usserahak managed to trade directly with Fleet in July 1632, despite interference by the Anacostans, and promised the Massawomecks would bring more beaver pelts to Great Falls. In August, Massawomecks from Tonhoga arrived at Great Falls.

Fleet traded away all of his "truck" and sailed downstream to the Piscataway town of Moyumpse. That town which may have been the home of the group also known as the Dogue, at the mouth of the Occoquan River. He was followed by "three cannibals of Usserahak, Tohoga, and Mosticum."

A small ship sailed from Jamestown and met Fleet at Moyumpse. On it was Captain John Uty, a member of the Council of Virginia. He notified Fleet that he was under arrest and required to go to Jamestown. Fleet had not stopped in Jamestown before sailing to Great Falls, and Governor John Harvey had not authorized his trading. Fleet considered simply sailing back to England with his furs, but chose to go to Jamestown. There he expected to negotiate approval from the colony's officials, obtain new supplies ("truck"( for additional trading, and load tobacco to which he was entitled due to previous dealings in Virginia.

At Jamestown he succeeded in resolving his arrest. He also had a new ship built to return to the Potomac River and trade further with the Massawomecks. There are no records documenting if that actually occurred, but when the first Maryland settlers arrived in 1634 they discovered the Massawomecks had already traded away the beaver supply of 1633 and the first part of 1634 to Henry Fleet and William Claiborne. Claiborne had established a trading post on Kent Island using authority granted in Jamestown before the creation of Maryland in 1632, and found the fur trade so valuable that he would be had for the Calverts to displace.

Cecil Calvert sent his brother to Maryland to serve as the new colony's first proprietary governor. He hired Henry Fleet as his guide and reached the Potomac River in March 1634. Calvert learned that the Massawomeck had been sending furs to the trading post at Quebec while it was under English control between 1629-1632. Quebec had been captured by David Kirke at the end of a war between France and England in 1629, and was not returned to French control until 1632.

Long before the English briefly controlled Quebec, the Massawomeck would have been acquiring metal products, textiles, glass beads, and other items from the French on the St. Lawrence River. The Iroquois interacted directly with the French traders starting in the late 1500's:16

- While small numbers of Europeans were in the Chesapeake Bay during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the Gulf of St. Lawrence was the undeniable focus of European commercial activity (trading, whaling, and fishing) at this time.... The Ontario Iroquoians did not need European goods from the Chesapeake. The constant supply from Basque and French traders in the Gulf of St. Lawrence provided Maritime and southern Ontario groups with quantities unheard of from archaeological sites around Chesapeake Bay, in Pennsylvania, and even New York State during the sixteenth century...

- With the onset of the commercial fur trade in the fourth quarter of the sixteenth century, Ontario Iroquoians initially received substantial amounts of Basque and French supplied goods from Native middlemen to the northeast in return primarily for beaver pelts.

Calvert reported that he had missed the chance to acquired beaver pelts by arriving so late in March 1634; Virginia traders had acquired the furs:17

- But by reason of our late arrivall here we came too late for the first part of the trade this year; which is the reason I have sent hom so few furrs - (they being dealt for by those Virginians before our crossing) - the second part of our trade is now in hand, and is like to prove very beneficiall. The nation we trade withal at this time a-year is called the Massawomeckes. This nation cometh seven eight and ten days journey to us - these are those from who Kircke had formerly all his trade of beaver. We have lost by our late comming 3000 skins, which other Virginians have traded for, but hereafter they shall come no more here, wherefore I make no doubt but next year we shall drive a very great trade if our supply of truck fail not.

After Calvert's report in 1634, there are no recorded eyewitness encounters of colonists with any Massawomecks. They appear to have been forced off their lands by raids from the Senecas around 1635. Susquehannocks then moved west to get away from European settlements in the mid-1600's, and occupied the former Massawomeck territory.18

In 1644, the Swedish colony on the Delaware River competed with the Dutch for beaver skins brought by the Black Minquas and White Minquas who lived to the west. The White Minquas were the Susquehannocks. The Black Minquas, who lived further west, likely included the Massawomecks. Over the next 20 years they were consolidated with members of the Erie, Neutral, and other tribes who had been defeated by the Haudenosaunee in the Beaver Wars. Shawnee and disaffected Senecas also melted into the Mingo community on the Ohio River. The Black Minquas wore a black badge, which may have been a cannel coal pendant.

Many of the Massawomeck may have moved east to the Susquehanna River after the 1650's and joined with the Susquehannocks as White Minquas.

They were composed of members of multiple tribal groups. Many of the Erie, Huron, Neutrals and other groups, after their defeat by the Haudenosaunee (five Iroquois tribes) in the Beaver Wars between 1640-1670. had been incorporated into the Seneca. That helped repopulate the Seneca, but not everyone was satisfied to remain within the Seneca towns. Some migrated southwest to the Ohio River in areas also occupied by the Shawnee and Miami nations and further from the Haudenosaunee.19

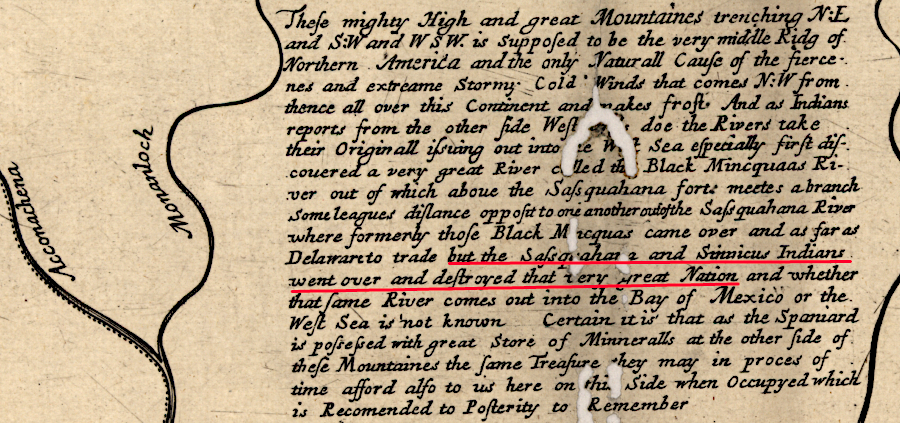

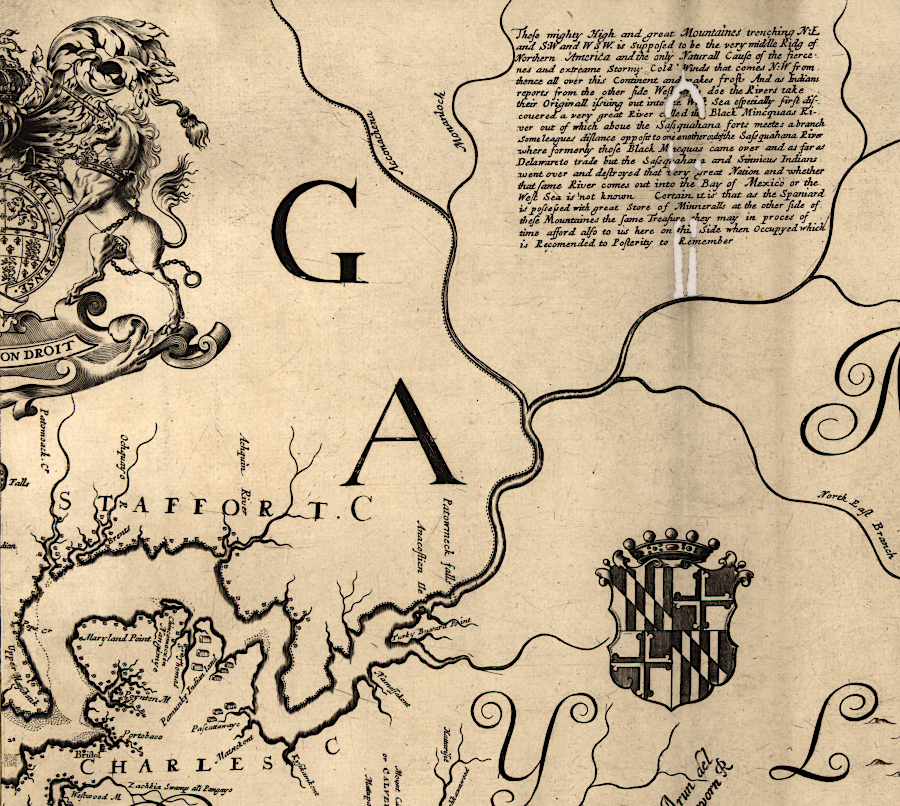

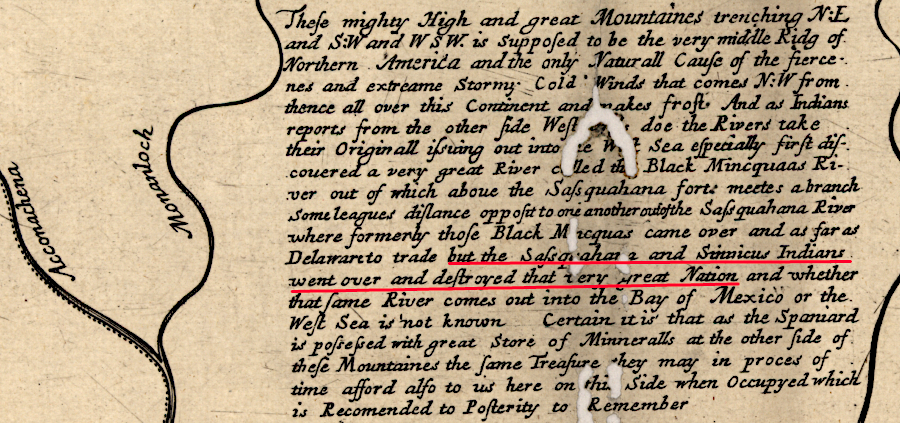

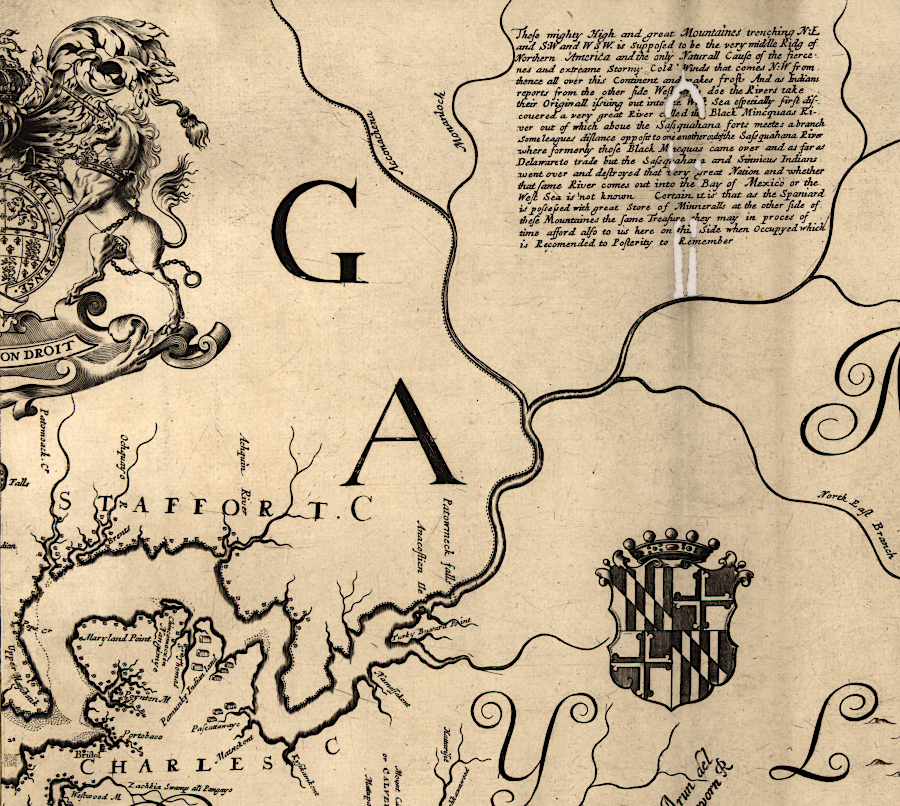

Augustine Hermann suggests, in a note on his 1670 map of Maryland and Virginia, that the Susquehannocks and Senecas forced the Massawomeck out of western Pennsylvania (emphasis added):20

And as Indians report from the other side [of the mountains] Westwards doe the Rivers take their Originall issuing out into the West Sea especially first discovered a very great

River called the Black Mincquaas River out of which above the Sassquahana forts meetes a branch some leagues distance opposite to one another branch out of the Sassquahana River where formerly those Black Mincquaas came over and as far as Delaware to trade but the Sassquahana and Sinnicus Indians went over and destroyed that very great Nation and whether that same River out into the Bay of Mexico or the West Sea is not known.

Minimal documentation makes it difficult to determine who were the Massawomecks and the evolution of the group. Most likely, the Massawomecks were disrupted by the Haudenosaunee and Susquehannocks during the Beaver Wars between 1640-1670. The culture and political organization of perhaps 30,000 people evolved into a melting pot with members of multiple tribes.

The Massawomecks, along with the Shawnee and other indigenous groups, were forced out of the Susquehanna/Ohio/Potomac watersheds by colonists. Massawomecks may have migrated with remnants of the Erie Nation south and been part of the "Rickahocan" group that appeared at the Fall Line of the James River in 1656. That group was later known as the Westo, when they moved to South Carolina in the 1670's. Some Massawomecks may have blended in with the Iroquoian-speaking Meherrin on the border of Virginia and North Carolina,

The Massawomecks who blended in with members of the Shawnee, Seneca, Delaware, and other Native American cultural groups became part of the Mingos (Black and White Minquas) living along the Ohio River. In the 1830's, the Native Americans in Ohio were displaced and forced to move west across the Mississippi River. Descendants of the Massawomecks are probably living now in two regions that are far from western Pennsylvania:21

- Today, there is a population of Massawomeck represented in the membership of the Meherrin tribe of North Carolina and the Seneca-Cayuga Nation of Oklahoma.

the Massawomeck may have evolved into the Black Minquas, after being forced west across the Ohio River by the Seneca and Susquehannock

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (Augustine Hermann, 1670)

Links

References

1. John Smith, "A true relation of such occurrences and accidents of noate as hath hapned in Virginia since the first planting of that collony," 1608, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A12470.0001.001; James F. Pendergast, "The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Part 2, 1991, pp.6-8, https://doi.org/10.2307/1006560 (last checked April 2, 2025)

2. Bernard G. Hoffman, "Observations on Certain Ancient Tribes of the Northern Appalachian Province," Smithsonian Institution, Anthropological Papers No. 70, 1964, pp.196-197, https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/22131/bae_bulletin_191_1964_70_191-246.pdf (last checked April 10, 2025)

3. John Smith, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles, 1624, p.33, https://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/smith/smith.html; James F. Pendergast, "The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Part 2, 1991, pp.9-10, https://doi.org/10.2307/1006560; William Wallace Tooker, "The Algonquian Terms Patawomeke and Massawomeke," American Anthropologist, Volume 7, Number 2 (April, 1894), pp.182-183, https://www.jstor.org/stable/658539; "A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century - Appendix C, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/jame1/moretti-langholtz/appendixc.htm (last checked August 4, 2025)

4. "A Closer Look: John Smith's Chesapeake Voyages," National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/john-smith-voyages.htm; John Smith, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles, 1624, p.33, https://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/smith/smith.html; James F. Pendergast, "The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Number 2 (1991), https://www.jstor.org/stable/1006560 (last checked August 4, 2025)

5. John Smith, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles, 1624, p.60-62, https://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/smith/smith.html (last checked April 2, 2025)

6. "Was Smith's gunpowder accident actually a murder plot?," Pocahontas Lives, https://www.pocahontaslives.com/was-smiths-gunpowder-accident-actually-a-murder-plot.html (last checked April 2, 2025)

7. "River and Mountain, War and Peace: Archeological Identification and Evaluation Study of Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park Hancock to Cumberland (Mile Markers 123 To 184), Volume I," National Park Service, May 2011, p.19, pp.27-28, https://npshistory.com/publications/choh/aie-v1-2011.pdf;

"Monongahela Culture," e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia Online, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/entries/1954; Robert Wall, Heather Lapham, "Material Culture of the Contact Period in the Upper Potomac Valley: Chronological and Cultural Implications," Archaeology of Eastern North America, Volume 31 (2003), https://www.jstor.org/stable/40914874; William H. Marquardt et alia, "The Protohistoric Monongahela and the Case for an Iroquois Connection" in Societies in Eclipse: Archaeology of the Eastern Woodlands Indians, A.D. 1400-1700, The University of Alabama Press, 2005, p.67, p.80, https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/181/monograph/chapter/47629; James B. Richardson III, David A. Anderson, Edward R. Cook, "The Disappearance of the Monongahela: Solved?," Archaeology of Eastern North America, Volume 30 (2002), https://www.jstor.org/stable/40914458 (last checked April 25, 2025>

8. Chuck Hamilton, "Lost Nation of the Erie Part 1," The Chattanoogan, January 21, 2016, https://www.chattanoogan.com/2016/1/21/316430/Lost-Nation-of-the-Erie-Part-1.aspx; "Mingo," e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia Online, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/entries/1771 (last checked April 7, 2025)

9. "First Hand Accounts," Virtual Jamestown, https://www.virtualjamestown.org/exist/cocoon/jamestown/fha/J1040 (last checked April 18, 2025)

10. Henry Fleet, "A Brief Journal of a Voyage made in the Bark Virginia, to Virginia and the other parts of the Continent of American," in Edward D. Neill, The English colonization of America During the Seventeenth Century, 1871, p.226, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015027039356?urlappend=%3Bseq=244%3Bownerid=13510798883990489-290; James F. Pendergast, "The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Part 2, 1991, pp.14-15, https://doi.org/10.2307/1006560 (last checked April 18, 2025)

11. Henry Fleet, "A Brief Journal of a Voyage made in the Bark Virginia, to Virginia and the other parts of the Continent of American," in Edward D. Neill, The English colonization of America During the Seventeenth Century, 1871, pp.226-229, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015027039356?urlappend=%3Bseq=244%3Bownerid=13510798883990489-290; "River and Mountain, War and Peace: Archeological Identification and Evaluation Study of Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park Hancock to Cumberland (Mile Markers 123 To 184), Volume I," National Park Service, May 2011, p.19, pp.27-28, https://npshistory.com/publications/choh/aie-v1-2011.pdf; Bernard G. Hoffman, "Observations on Certain Ancient Tribes of the Northern Appalachian Province," Smithsonian Institution, Anthropological Papers No. 70, 1964, pp.199-201, https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/22131/bae_bulletin_191_1964_70_191-246.pdf (last checked April 18, 2025)

12. William R. Fitzgerald, "Reviewed Work: 'The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Part 2 by James F. Pendergast,' Canadian Journal of Archaeology/Journal Canadien d'Archéologie, Volume 16 (1992), https://www.jstor.org/stable/41102863; William H. Marquardt et alia, "The Protohistoric Monongahela and the Case for an Iroquois Connection" in Societies in Eclipse: Archaeology of the Eastern Woodlands Indians, A.D. 1400-1700, The University of Alabama Press, 2005, p.79, https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/181/monograph/chapter/47629 (last checked April 21, 2025)

13. Robert Wall, Heather Lapham, "Material Culture of the Contact Period in the Upper Potomac Valley: Chronological And Cultural Implications," Archaeology of Eastern North America, Volume 31 (2003), p.171, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40914874 (last checked April 23, 2025)

14. Henry Fleet, "A Brief Journal of a Voyage made in the Bark Virginia, to Virginia and the other parts of the Continent of American," in Edward D. Neill, The English colonization of America During the Seventeenth Century, 1871, p.230, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015027039356?urlappend=%3Bseq=244%3Bownerid=13510798883990489-290; James F. Pendergast, "The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Part 2, 1991, p.16, pp.229-230, https://doi.org/10.2307/1006560 (last checked April 19, 2025)

15. Henry Fleet, "A Brief Journal of a Voyage made in the Bark Virginia, to Virginia and the other parts of the Continent of American," in Edward D. Neill, The English colonization of America During the Seventeenth Century, 1871, pp.230-231, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015027039356?urlappend=%3Bseq=244%3Bownerid=13510798883990489-290; James F. Pendergast, "The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Part 2, 1991, p.16, https://doi.org/10.2307/1006560 (last checked April 19, 2025)

16. William R. Fitzgerald, "Reviewed Work: 'The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Part 2 by James F. Pendergast,' Canadian Journal of Archaeology/Journal Canadien d'Archéologie, Volume 16 (1992), https://www.jstor.org/stable/41102863 (last checked April 21, 2025)

17. James F. Pendergast, "The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Part 2, 1991, pp.14-18, pp.234-236, https://doi.org/10.2307/1006560; "KIRKE (Kertk, Quer(que), Guer), Sir DAVID," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kirke_david_1E.html (last checked April 19, 2025)

18. James F. Pendergast, "The Massawomeck: Raiders and Traders into the Chesapeake Bay in the Seventeenth Century," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 81, Part 2, 1991, p.1, pp.14-15, https://doi.org/10.2307/1006560; Robert Wall, Heather Lapham, "Material Culture of the Contact Period in the Upper Potomac Valley: Chronological and Cultural Implications," Archaeology of Eastern North America, Volume 31 (2003), https://www.jstor.org/stable/40914874; William H. Marquardt et alia, "The Protohistoric Monongahela and the Case for an Iroquois Connection" in Societies in Eclipse: Archaeology of the Eastern Woodlands Indians, A.D. 1400-1700, The University of Alabama Press, 2005, p.80, https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/181/monograph/chapter/47629 (last checked April 21, 2025>

19. Bernard G. Hoffman, "Observations on Certain Ancient Tribes of the Northern Appalachian Province," Smithsonian Institution, Anthropological Papers No. 70, 1964, pp.201-207, https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/22131/bae_bulletin_191_1964_70_191-246.pdf; William H. Marquardt et alia, "The Protohistoric Monongahela and the Case for an Iroquois Connection" in Societies in Eclipse: Archaeology of the Eastern Woodlands Indians, A.D. 1400-1700, The University of Alabama Press, 2005, pp.80-82, https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/181/monograph/chapter/47629 (last checked April 23, 2025>

20. "River and Mountain, War and Peace: Archeological Identification and Evaluation Study of Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park Hancock to Cumberland (Mile Markers 123 To 184), Volume I," National Park Service, May 2011, p.19, p.28, https://npshistory.com/publications/choh/aie-v1-2011.pdf; "Monongahela Culture," e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia Online, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/entries/1954 (last checked April 7, 2025>

21. "Westo Indians," Peach State Archeological Society, https://peachstatearchaeologicalsociety.org/cultural-histories/historic-european-contact-period/westo-indians/; Bernard G. Hoffman, "Observations on Certain Ancient Tribes of the Northern Appalachian Province," Smithsonian Institution, Anthropological Papers No. 70, 1964, pp.211-221, https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/22131/bae_bulletin_191_1964_70_191-246.pdf; "Native Lands Of Pennsylvania," Haudenosaunee Confederacy, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f25979811cf5437e9c462694e83a9f82 (last checked April 18, 2025)

"Indians" of Virginia - the Real First Families of Virginia

Exploring Land, Settling Frontiers

Virginia Places