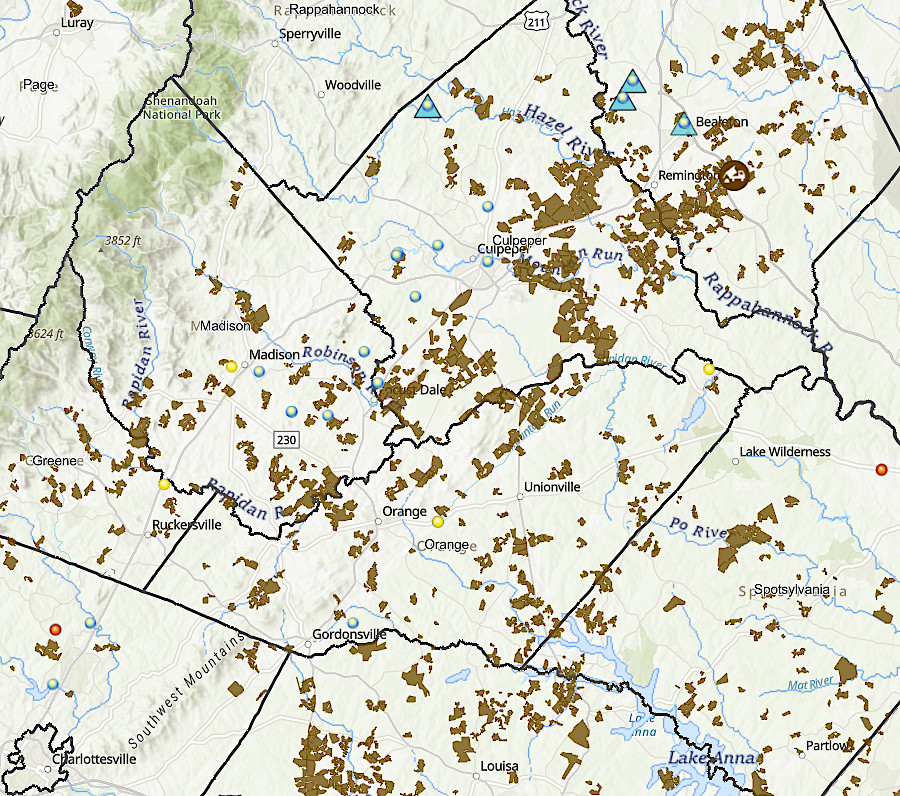

counties where biosolids were applied in 2007, showing tons of nitrogen per county

Source: Virginia Tech, Virginia County-Level Historical Trends

counties where biosolids were applied in 2007, showing tons of nitrogen per county

Source: Virginia Tech, Virginia County-Level Historical Trends

Humans and animals produce biosolids. Though dog owners know the joys of collecting biosolids after walking the pet, most human biosolids are just flushed down a toilet. In some cases, however, what we flush will be recycled to farmland or forests - after processing.

All waste ends up in either the air, the water, or in the ground. In rural areas, waste goes through septic tanks and leach fields. Organic materials are converted by bacteria into carbon dioxide and nutrients in the soil, and humans never see any residue unless the septic tank is cleaned out.

In Tidewater cities/counties affected by the Chesapeake Bay regulations in Virginia, septic tanks must be pumped out every 5 years to remove any grease, clogs, and non-organic solids in the tank (such as cigarette filters or plastic flushed down the toilet). Preventive cleaning helps ensure septic systems work as designed. When a septic system fails, raw sewage can reach the surface of a leach field and contaminate lawns, or flow underground to contaminate nearby creeks.

"Honey wagons" that pump out septic tanks carry the remaining solids (septage) from the underground concrete vaults to a sewer system manhole. The solids are pumped from the "honey wagon" into the sewer, and they then flow down the sewer pipe to a wastewater treatment plant. There, the inorganic solids and large objects are screened out. Typically they are incinerated or buried underground at a landfill.

Organic solids dissolved in the wastewater are converted at the treatment plant by bacteria into gas (especially N2 and CO2). The gas rises up into the atmosphere. The "reclaimed" wastewater flows at the end of the treatment process into a nearby creek or river.

Some organic grease/scum accumulates at the top of the settling and clarifying tanks near the end of the process at wastewater treatment plants. Wastewater treatment depends upon microorganisms in "activated sludge" to consume the organic material delivered by sewer pipes. Nitrogen and phosphorous are isolated from the wastewater, moving into the cells of the bacteria. The bacteria accumulate as sludge at the bottom of various basins and tanks in treatment facilities.

The sludge is regularly removed from the tanks and dewatered. The solids can be trucked away and buried in a landfill, but that is expensive. Sewage sludge can be incinerated so a smaller volume of ash can buried in a landfill. That is still expensive, and burning sewage sludge generates emissions that may disturb people living nearby.

An alternative is to capture the biosolids during the treatment process, then process them enough chemically so the waste solids are safe to spread as fertilizer and a soil amendment to increase the percentage of organic matter in agricultural/forest soils. The nutrient-rich biosolids enhance plant growth so crops and pasture grasses produce more food. Some of that food, after consumption by humans, ends up getting flushed down toilets and returns to a wastewater treatment plant.

King County, Washington refers to the process of recycling organic waste from the treatment plant into fertilizer and then food as the "Poop Loop." Across the United States:1

organic waste that is not digested by bacteria is extracted from wastewater, mostly in the primary and secondary treatment stages

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Richmond Wastewater Treatment Plant in Richmond, Virginia

In Arlington County, the wastewater treatment plant on Four Mile Run near Reagan National Airport has politically-influential and wealthy neighbors living in high value homes on Arlington Ridge. The residents objected to the incineration of sludge at the facility, objecting to impacts on local air quality. They also claimed the emissions from incineration process could lower their property values.

In response, Arlington abandoned burning the large volume of sludge produced in primary and secondary treatment. Arlington tore down the incinerator smokestack to make clear that the sludge would never be burned again. The county has continued to incinerate the inorganic solids screened out of the wastewater at the start of the process, but ships the solids to the Alexandria/Arlington Waste-to-Energy Facility for incineration.

Arlington County has no landfill nearby for disposal of the sludge which accumulates daily at the treatment plant. On an annual basis, assuming each residents generates the national average of 37 pounds of biosolids per person, the county must deal with about 4,500 tons of biosolids. To put that number into context, a dump truck carries 10 tons per load, so the Arlington County Water Pollution Control Plant produces over a dump truck load of biosolids each day.2

The county's solution is to treat the sludge enough to convert it into "Class A biosolids" that pose no health risk. Trucks now haul away the biosolids to be spread on the soil at farms and forests in rural areas of Virginia.

Arlington County is fully urbanized; there are no large farms where the biosolids could be applied. The county pays a contractor to obtain permission for disposal elsewhere, and to transport the "once waste, now nutrient" material to farms and forests. Human waste from people in the sewershed of the Arlington wastewater treatment plant is recycled into grass or trees, as plants and organisms in the soil incorporate nutrients and trace elements provided by the biosolids.

Richmond's biosolids are applied on farms in Amelia, Buckingham, Caroline, Charles City, Charlotte, Cumberland, Hanover, King William, and Powhatan counties

Source: City of Richmond, Biosolids

Under the Environmental Protection Agency's regulations (the 503 Rule), there are two classes of biosolids. To create Class A biosolids, sludge is treated to eliminate nearly all disease-causing organisms (pathogens) and to minimize heavy metals. Class A biosolids can be upgraded to Exceptional Quality (EQ) biosolids if processed (typically by heat of adding lime to increase pH) so birds, flies, and other vectors will not be attracted to the material. Class A biosolids are handled like commercial fertilizers when spread on farms, while EQ biosolids can be bagged and sold to homeowners for use without any special restrictions.

Class B biosolids may retain detectable levels of pathogens and metals. The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) requires a site permit before authorizing application of Class B biosolids, and limits the application of Class B biosolids near streams/sinkholes and on steep slopes.3

About 60 percent of sewage sludge in the United States was used for land application in 2002. In Virginia, biosolids were applied to about 50,000 acres in 2006. By comparison, untreated animal manure was applied to nearly 400,000 acres.4A recently-eaten hamburger may have come from a cow that grazed on grass which was fertilized by biosolids from a Virginia wastewater treatment plant. The most recent birthday card may have been created from pulp from a pine forest that was fertilized by biosolids. The toilet paper last used could have come from such a forest, making the recycling cycle even more obvious...

Modern urban living emphasizes cleanliness, and antiseptics fill our medicine cabinets and cleaning closets. As a result, many Virginians are ignorant of how their waste is processed and have an "out of sight, out of mind" after we flush. It is typical to get a squeamish reaction when discussing how human waste is applied to farm fields. If the farm field is nearby, the reaction is often much stronger than just "Eeew... gross."Virginia wastewater treatment plants do not ship their biosolids to Ohio or Kansas. To reduce costs, urban wastewater treatment plants haul their biosolids to nearby farms. In many suburbanizing areas, the nearest farms are getting surrounded by modern subdivisions. Houses near the farms are filled with squeamish voters who are unfamiliar/uncomfortable with the idea that human waste, no matter how safe, is going to be dumped nearby.

Land application of biosolids requires various permits, and in many cases the approval process is controversial. Counties have tried to pass local ordinances, often in the guise of zoning for land use control, that limit where biosolids could be applied.

Federal and state regulations supersede local ordinances. The General Assembly consolidated state permitting into the Department of Environmental Quality starting in 2008, shifting responsibilities from the Virginia Department of Health. Virginia counties may impose fees and require additional testing/monitoring of land application sites, but may not block land application.

biosolids application starts with hauling the nutrients to a site, then spreading them

Source: Virginia Cooperative Extension, Agricultural Land Application of Biosolids in Virginia: Risks and Concerns

In addition to biosolids generated at wastewater treatment plants from human sewage, "Industrial sludge" is produced from waste at animal processing plants and paper mills.

In 2014, the State Water Control Board was asked by Synagro Technologies to approve use of industrial sludge generated by the Tyson Foods poultry processing plant in Hanover County, the RockTenn Co. paper mill at West Point, and the Smithfield Foods pork processing plant in Isle of Wight County. The application would occur on 16,000 acres in King William, King & Queen, New Kent, Goochland, Hanover, Prince George and Surry counties.5

Acres Permitted for Biosolids Applications, by County, 2004 (wastewater treatment plants in southwestern counties were not disposing of biosolids by land application)

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Review of Land Application of Biosolids in Virginia (House Document No. 89, 2005)

Whatever is flushed into sewers will be processed at a wastewater treatment plant, but the treatment processes at those facilities do not remove all materials of concern. Pharmaceuticals such as estrogen from birth control pills and "forever chemicals" such as Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) can end up in the sludge which is applied as fertilizer. Between 2007-2022, Class B or better sludge was applied on at least 9,600 sites in Virginia.

Nationwide, it has been used on about 70 million acres, roughly 20% of all agricultural land in the United States.

Sludge is not land applied in Virginia until it has been tested for metals and pathogens, but by 2024 only Maine was testing sludge for PFAS. No Virginia wastewater treatment plant was using its authority under the Clean Water Act to require facilities to pretreat and eliminate PFAS before discharging waste into sewers. The 2025 General Assembly passed HB2050, which required all facilities discharging waste in the watershed leading to the Occoquan Reservoir to reduce PFAS levels so they did not exceed the Maximum Contaminant Level for drinking water.

Maine was also the only state at that time to prohibit land application of sludge from wastewater treatment plants. Testing for PFAS and other contaminants could require building expensive storage facilities to hold the material until test results become available.

Back in the 1990's, a scientist working for the Environmental Protection Agency had warned about recycling sludge onto agricultural fields, writing:6

As of 2025, Virginia had authorized disposal on farmland of wastewater sludge from 22 Maryland wastewater treatment plants. As that state began to limit disposal of biosolids on its agricultural lands, Synagro requested approval to spread material from Maryland on more acreage in Westmoreland and Essex counties. Oyster farmers expressed concern that runoff from farmland would impact PFAS levels within their product, potentially impacting marketability.

A member of the Virginia State Water Control Board said:7

Source: Virginia Conservation Network, PFAS, Sewage Sludge, & Farmlands

The "don't spread on me" campaign in Albemarle County determined that the Synagro sought permits to spread biosolids on up to 5,770 acres in the county. Almost all sources of the sewage sludge were wastewater treatment plants in Northern Virginia, Maryland, and Washington DC.8

"brown polygons show sites where biosolids application has been permitted northeast of Charlottesville

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Biosolids Application Areas in Virginia