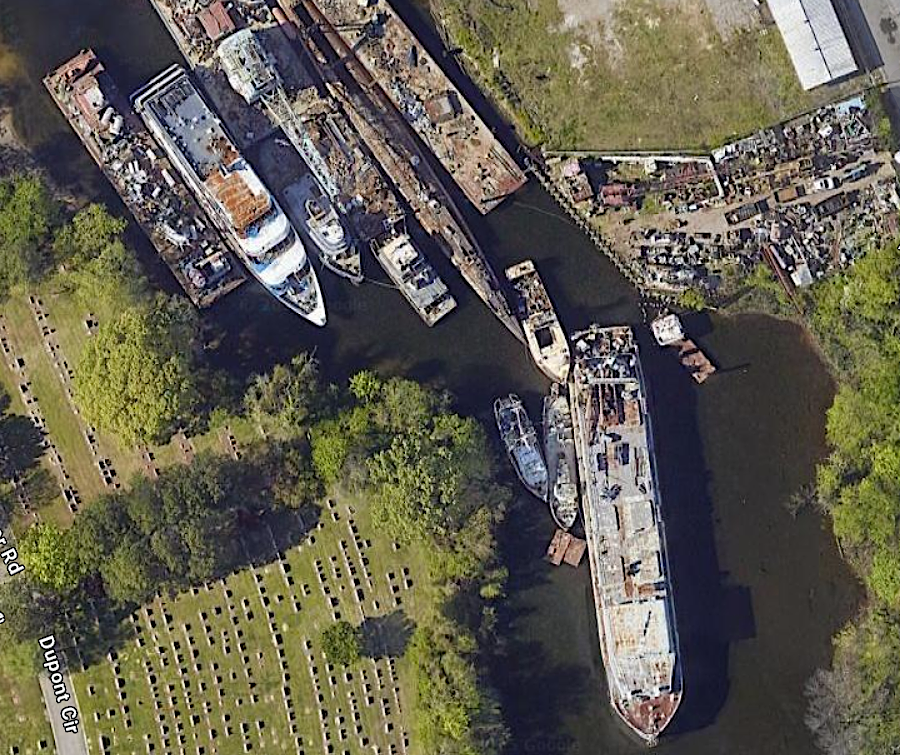

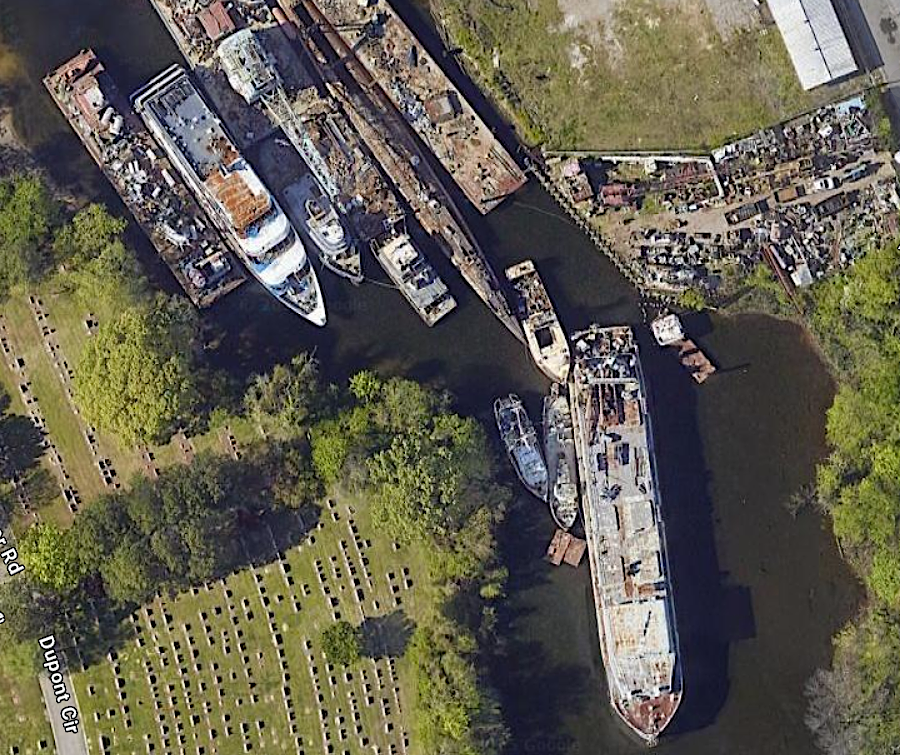

Colonna's Shipyard stockpiles boats to be recycled next to Riverside Memorial Cemetery in Portsmouth

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Colonna's Shipyard stockpiles boats to be recycled next to Riverside Memorial Cemetery in Portsmouth

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Large boats are scrapped at shipyards in Hampton Roads, since the value of the recovered metal makes recycling cost-effective. Smaller boats are a problem.

The development of low-cost fiberglass boats in the 1960's was followed 50 years later by the challenge of disposing of old boats which did not decompose. The material in a fiberglass boat has little value for reuse; the cost for disposal exceeds the value of a worn-out boat, and the fine for unauthorized disposal is only $500.

The Executive Director of Clean Virginia Waterways summarized the challenge:1

Not surprisingly, many owners have simply abandoned their boats. Abandoned and Derelict Vessels (ADV's) have accumulated in marshes, along riverbanks, and even in marinas. The vessels create navigation hazards and environmental risks from petroleum products, paint, and plastics. The visibility and size of unusable boats draws attention, though the greatest percentage of marine debris consists of plastic items from land-based sources.2

most marine debris consists of small plastic items that do not biodegrade quicky, but abandoned and derelict vessels attract attention

Source: Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program, 2021-2025 Virginia Marine Debris Reduction Plan (p.6)

Derelict boats are a form of marine trash. Disposing of that waste is easiest when an owner can be identified and contacted. The process is more challenging if no responsible party for disposal can be assigned the responsibility and cost of removal.

The Code of Virginia requires that most motorboats be registered and display a number issued by the Department of Wildlife Resources. By law, owners of motorized boats must notify that department if they abandon the boat:3

it is less expensive to abandon vessels rather than pay for proper disposal

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Abandoned and Derelict Vessels in Virginia

State law defines a legal mechanism for property owners to acquire ownership of abandoned boats. That process has value only if the boat has value.

The Department of Wildlife Resources administers the Marine Habitat and Waterways Improvement Fund, which finances removal of abandoned and derelict boats. In addition to state appropriations, the fund receives money from the sale of state-owned marine lands and from donations.

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission also has the power to remove derelict and abandoned boats from public waterways. According to state law:4

Source: Clean Virginia Waterways of Longwood University, Abandoned & Derelict Vessels in Virginia: Impacts on Environment, Economy, and Navigational Safely

Relatively inexpensive fiberglass boats became widely available starting in the 1970's. After years of use, many were no longer worth the cost of repairs. The Virginia Coastal Zone Management (CZM) Program, established in 1986 and led by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), included "Goal 4: Understand, Prevent and Mitigate the Impacts of Abandoned and Derelict Vessels" with eight action items, including creating a GIS-based inventory of derelict vessels to prioritize removals.

Virginia Marine Debris Summits were held in 2016 and 2019, and the Virginia Abandoned and Derelict Vessel Work Group was formed in 2020. The 2021-2025 Virginia Marine Debris Reduction Plan identified the need for an up-to-date database to inventory known Abandoned and Derelict Vessels in Virginia waters.5

finding recycling options for fiberglass and increasing capacity for removing boats are two action items in the 2021-2025 Virginia Marine Debris Reduction Plan

Source: Virginia Coastal Zone Management (CZM) Program, 2021-2025 Virginia Marine Debris Reduction Plan (p.35)

The 2023 General Assembly provided $3 million to a grant program helping localities remove "Abandoned and Derelict Vessels." The Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) administered the grant program.

Lynnhaven River NOW obtained a separate $3 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to remove 100 boats. To interrupt the expected pattern of boat removals being followed by abandonment of new vessels in the same area and perpetuating a boat graveyard, Lynnhaven River NOW and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission began to explore how to create a statewide boat recycling or buy-back program. A leader in Lynnhaven River NOW said in 2023:6

a site on the North Landing River next to the Chesapeake/Virginia Beach border has become a boat graveyard

Source: Clean Virginia Waterways of Longwood University, Abandoned & Derelict Vessels in Virginia: Impacts on Environment, Economy, and Navigational Safely

By the end of 2023, the Vessel Disposal Reuse Foundation in Hampton Roads had removed 29 boats and more than 300,000 pounds of debris from waterways. By the end of 2024, that had climbed to 70 boats and 675,000 pounds removed.

The non-profit organization, funded by donors, estimated in 2023 that there were still 200 abandoned and derelict vessels in Virginia. Most in the Hampton Roads region, particularly in boat graveyards in London Bridge Creek and the North Landing River. If a boat is not removed before it sinks, disposal costs typically increase 400%.

abandoned boat on the North Landing River

Source: Vessel Disposal & Reuse Foundation, WAVY 10 NLR Boat Graveyard

Cost of legal disposal, averaging about $14,000 per vessel, was the reason for most boats to be abandoned. The one landfill in Hampton Rads that accepted boats charged $150 per linear foot, so the larger the boat the greater the disposal costs. Boat owners were advertising that they would sell a boat for $1, in order to avoid the maintenance and liability costs.

The foundation's executive director recognized that boat owners without much disposable income had no feasible way to dispose of their vessel. Punishing such owners under the law would not remove boats from the water:7

getting rid of non-functional boats is a nationwide problem

Nonetheless, in 2024 Portsmouth made it a Class 1 misdemeanor to abandon a boat in public waters.

The Vessel Disposal Reuse Foundation, Lynnhaven River Now, the Elizabeth River Project, and the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program had plans in 2025 to remove abandoned or derelict boats. Removal required completing environmental reviews for potential impacts and by the Virginia State Historic Preservation Office.

There were 20 such boats in Willoughby Bay and six in the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River, plus others in scattered locations. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) awarded a $2.9 million grant from the Marine Debris Program to Lynnhaven River Now. The initiative included deterring people from abandoning boats in the future. The Executive Director of Lynnhaven River Now said:8

most marine debris consists of small plastic items that do not biodegrade quicky, but abandoned and derelict vessels attract attention

Source: Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program, 2021-2025 Virginia Marine Debris Reduction Plan (p.6)

all states with navigable waterways have to deal with abandoned boats that leak oil and gasoline, clog channels, and shed plastics into the water

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Abandoned and Derelict Vessels in Michigan