Prelude to the Revolutionary War in Virginia

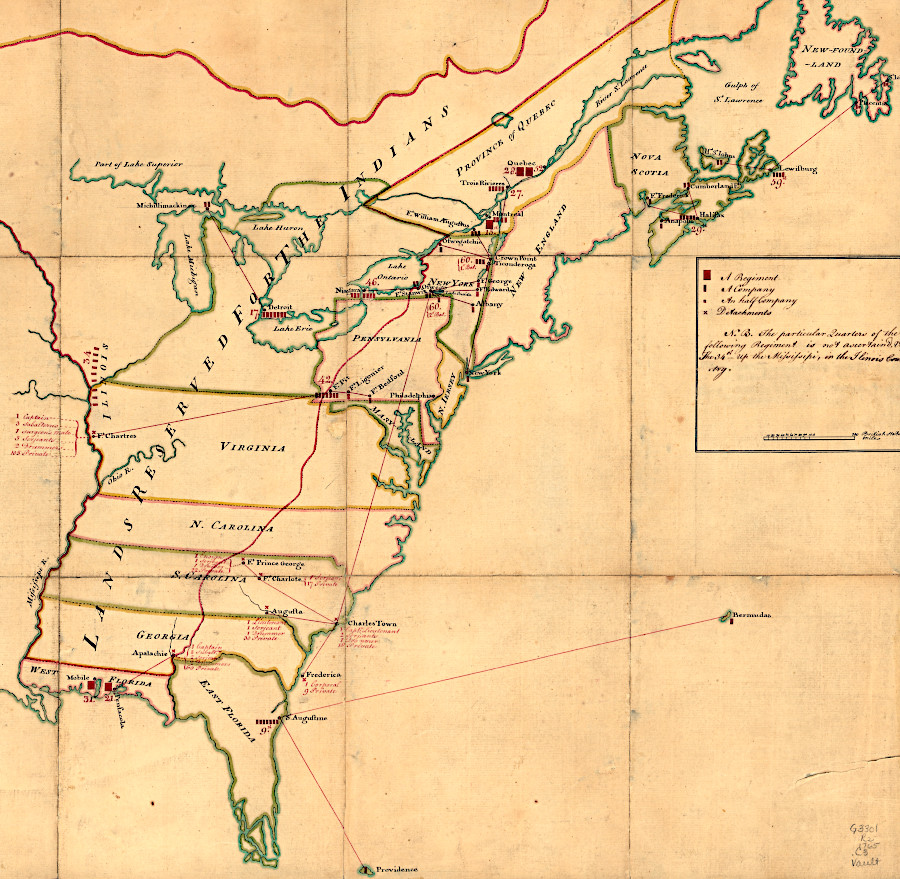

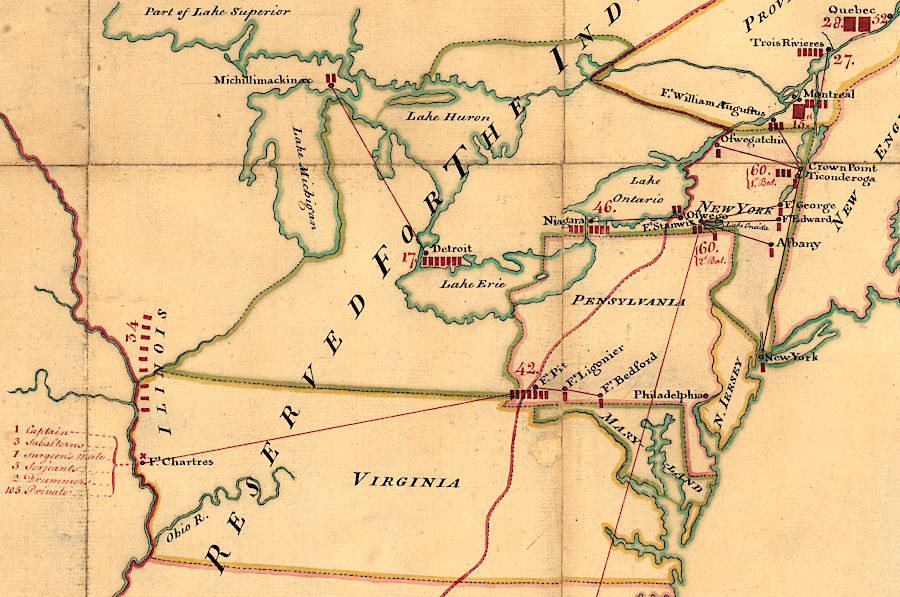

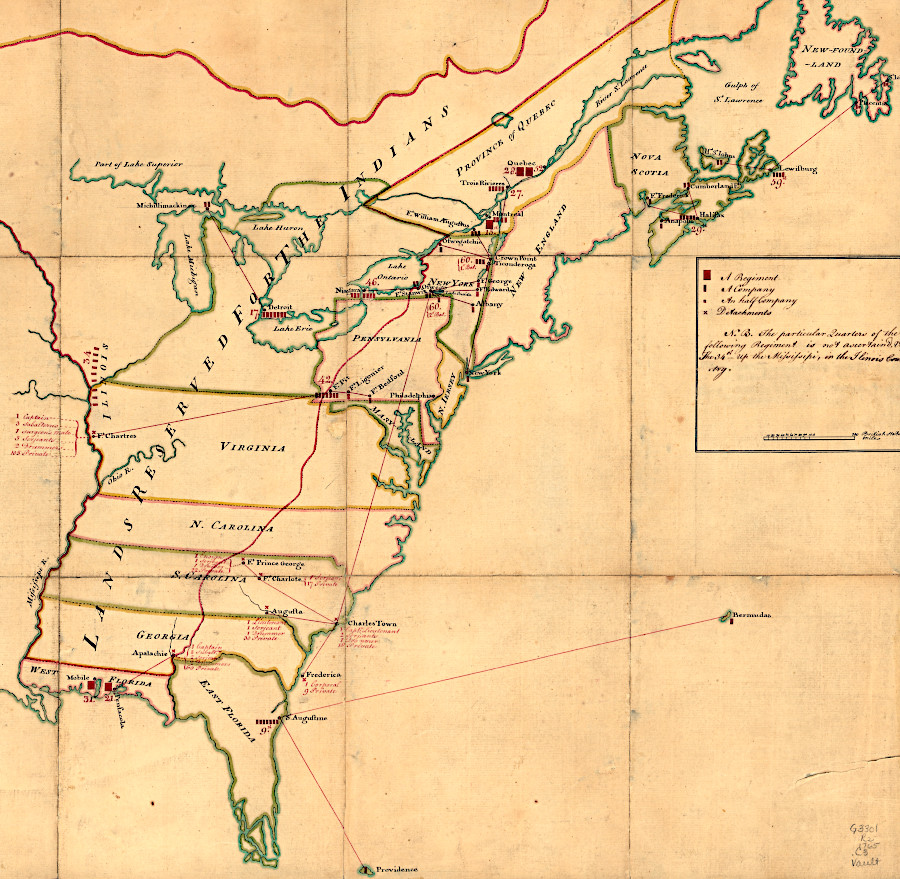

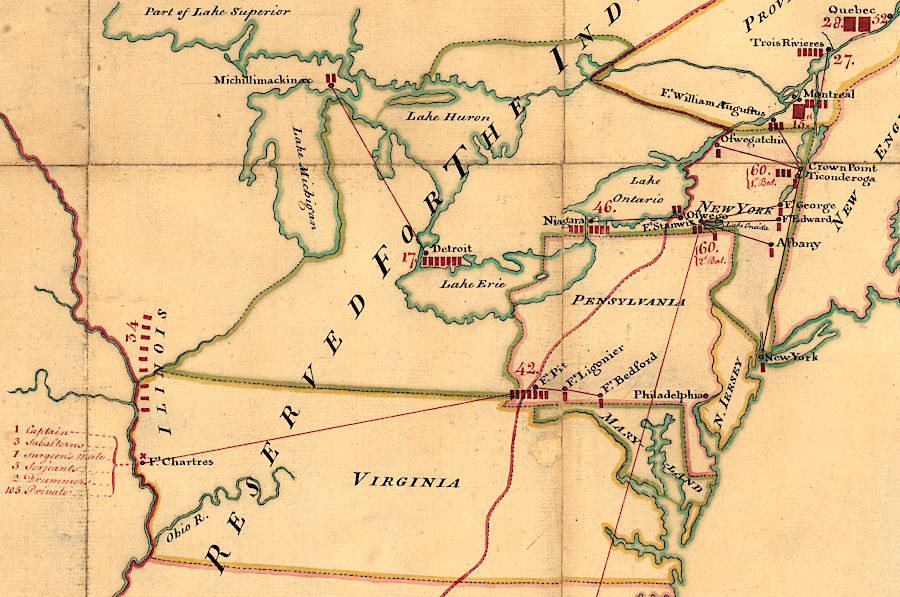

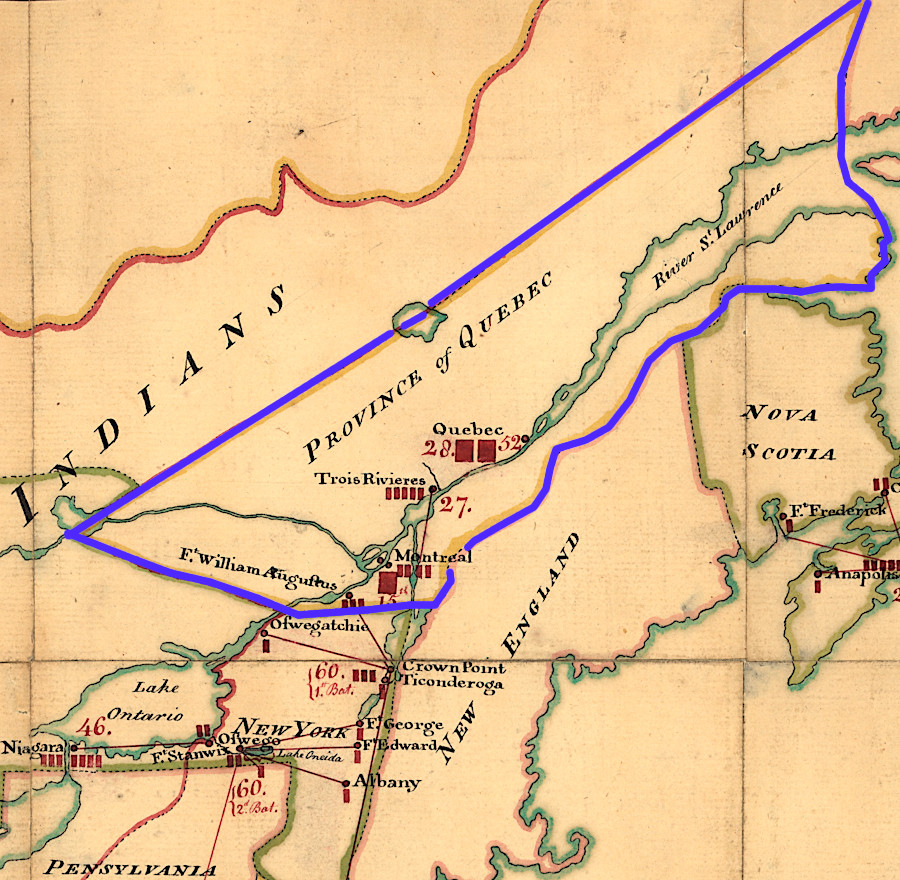

during the Stamp Act crisis in 1765, the largest number of British troops in Virginia were based at Fort Chartres (Prairie du Rocher) on the Mississippi River, far from Williamsburg

Source: Library of Congress, Cantonment of the forces in North America 11th. Octr. 1765

The start of the American Revolution could be dated to the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. Over the course of a dozen years before actual fighting began, American colonists began to identify that their economic and political interests were different from the agenda of Parliament and King George III.

Virginians should have been satisfied with the results of the French and Indian War, and even grateful for the military resources transported from Great Britain across the Atlantic Ocean. French claims to the Ohio Country had been eliminated, no longer able to mobilize Native Americans to contest control over western lands. The gentry who controlled Virginia's economic, political, and social life could add to their wealth. Through the Ohio Company, Loyal Land Company, and other arrangements, the well-connected families were granted land for free in exchange for recruiting people willing to purchase and settle on it.

The major disappointment in 1763 was that the military road built to capture Fort Duquesne at the Forks of the Ohio River ended up being carved through the Pennsylvania wilderness. Braddock's road from Alexandria, if completed by General Forbes rather than a road from Lancaster, would have increased access to western lands from Virginia and accelerated land sales.

Great Britain was deep in debt in 1763. The government had borrowed heavily to finance what Europeans called the Seven Years War. The conflict between France and Great Britain had morphed into the first world war, after George Washington's task force in 1754 led to the murder of a French diplomat in the wilderness near Fort Duquesne. The expansion of the Royal Navy and army had been expensive. Great Britain ended up with a larger empire in 1763, but he national debt had increased from £74 million to £133 million. Maintaining the additional military forces to protect the newly-acquired territory in North America would require additional public funding.

British officials decided that it was only fair for the American colonists to help pay for the expensive war which had forced France out of North America:1

- Britain was able to, in a fashion, purchase an empire following the victorious Seven Years' War by merely spending more and accruing lower interest rates on its debt than the enemy did. However, the massive empire gained by Britain was a hollow victory, since the obligations of gathering public debt also contained implicit promises of payback and/or return on investment for the buyer, which included many prominent British citizens. Thus, the government attempted to equalize the burden of debt.

When George III issued the Proclamation of 1763, he established a limit on western expansion. That proclamation was designed to minimize the costs of future conflict with the Native Americans. Drawing a line at the watershed divide of the Atlantic Ocean-Gulf of Mexico would, at least in theory, separate settlers and Native Americans. Separation would minimize conflict which might require a military response. However, that line blocked efforts of the politically-influential colonial elite to acquire new land grants or to take advantage of land claims already acquired.

The American Revolution ended up being led by the elite of colonial society, men in power who saw a threat to their ability to gain and retain wealth. It was not a social revolution in which the lower classes rebelled against inequality and redistributed wealth and power. At the end of the American Revolution, the same elite Americans remained in charge as at the start. That result offers a clear contrast to the English, French, and Russian revolutions in which Charles I, Louis XIV, and Tsar Nicholas II were executed.

The Proclamation of 1763 did not physically block settlers from crossing the divide and settling in the Mississippi River watershed. However, the edict did block the wealthy elite from selling the land which they had obtained through grants. Shareholders in speculative land companies, particularly the Ohio Company and the Loyal Land Company, were blocked from cashing in.

The 1764 Sugar Act was the first attempt by Parliament to generate revenue from the colonists in order to pay off the loans obtained to finance the French and Indian War. Under the Sugar Act of 1764, Americans had to pay tariff duties on all imported molasses, coffee, textiles, and wine.

The Sugar Act impacted importers and distillers in the northeastern colonies, who manufactured rum from the molasses created as sugar was refined on Caribbean islands. Based on the assumption that colonial juries would not convict smugglers, the Sugar Act created vice-admiralty courts where trials could be held without a jury.

The First Lord of the Treasury, George Grenville, told King George III:2

- ...it is just and necessary, that a revenue be raised, in your Majesty's said dominions in America, for defraying the expences of defending, protecting, and securing the same.

Resistance to the Sugar Act taxes spurred creation of Committees of Correspondence so different colonies could coordinate boycotts as a response. Parliament ignored American objections and passed the Stamp Act in 1765, taxing all legal documents as well as the printing of newspapers and pamphlets. Prime Minister Grenville projected that the revenue would cover up to 20% of the costs for maintaining British troops in North America.

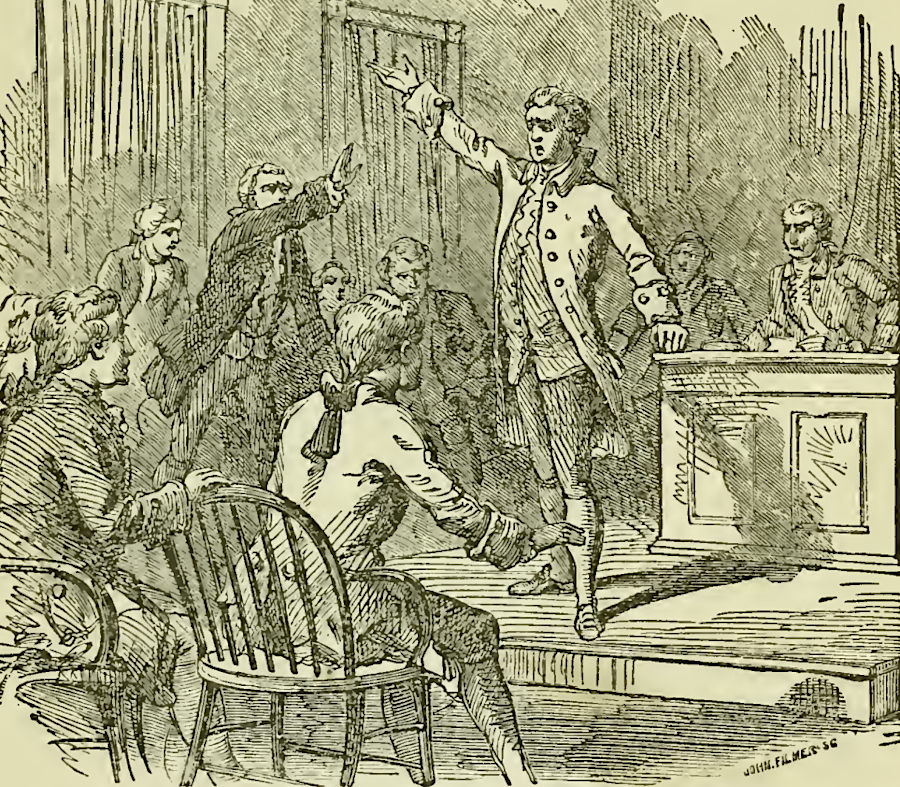

In Virginia, the House of Burgesses passed the Stamp Act Resolves to express opposition to the direct tax imposed on the colonies. During the debate, Patrick Henry's suggestion that King George III could meet the same fate as Caesar and King Charles I led to cries of "treason" from other burgesses.

Mobs, some organized as Sons of Liberty, threatened officials who prepared to collect the stamp tax. In Williamsburg, Governor Fauquier had to personally escort the official tax collector, George Mercer, from the steps of Charlton’s Coffeehouse to the Governor's Palace to ensure his safety.

The House of Burgesses had passed the most radical of his proposals by just one vote, and rescinded its approval the next day. With or without official approval, that resolution became a widely accepted belief among the colonists that Parliament was proposing direct taxes that threatened rather than protected fundamental liberties:3

- Resolved, Therefore that the General Assembly of this Colony have the only and sole exclusive Right and Power to lay Taxes and Impositions upon the Inhabitants of this Colony and that every Attempt to vest such Power in any Person or Persons whatsoever other than the General Assembly aforesaid has a manifest Tendency to destroy British as well as American Freedom.

The 1765 Sugar Act and the 1765 Stamp Act also targeted the top tier of society, especially ship owners, publishers and lawyers. They effectively shaped the opinion of the majority of colonists. Support for Parliament and King George III was replaced by support for colonial autonomy from Great Britain. Joseph Galloway, a leader in the Pennsylvania Assembly, wrote to Benjamin Franklin in 1765:4

- I cannot describe to you, the indefatigable Industry that have been and are constantly taking by the Prop--y Party and Men in Power here to prevail on the People to give every Kind of Opposition to the Execution of this Law. To incense their Minds against the King Lords and Commons, and to alienate their Affections from the Mother Country. It is no uncommon thing to hear the Judges of the Courts of Justice from the first to the most Inferiour, in the Presence of the attending Populace, to Treat the whole Parliament with the most irreverent Abuse.

The 1765 Stamp Act triggered a stronger response than the Sugar Act because it taxed good used within the colonies. A stamp tax was already a common element in England, but new to America. American colonists made clear that they objected to sending scarce specie (gold and silver) to London to pay the taxes. Opponents in Boston organized a mob that destroyed the home of Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. In 12 of the 13 colonies, threats of violence forced the appointed stamp distributors to resign.

"Taxation without representation." barriers to continued western land speculation, limits on manufacturing raw products into saleable items, and barriers to trade with other nations would constrain the potential to grow or retain wealth in America. British policy had been designed to transfer wealth from Virginia to England since 1607. Seemingly without recognizing the hypocrisy in a society based on the labor of enslaved men and women, Tidewater planters started to complain in the 1760's that they were being converted into slaves of Great Britain.

In response to the Stamp Act, a new member of the Virginia House of Burgesses drafted seven resolutions for the House of Burgesses to articulate its opposition to the Stamp Act. Young and impatient Patrick Henry introduced five of his resolutions on May 29, 1765. The most radical of the Virginia Resolves, the fifth resolution, triggered calls of "treason" when Patrick Henry championed it.

The fifth resolution, which was approved by a 20-19 vote on May 30, said:5

- Resolved, Therefore that the General Assembly of this Colony have the only and sole exclusive Right & Power to lay Taxes & Impositions upon the Inhabitants of this Colony and that every Attempt to vest such Power in any Person or Persons whatsoever other than the General Assembly aforesaid has a manifest Tendency to destroy British as well as American Freedom.

That resolution was repealed a day after initial approval. The burgesses who had chosen to remain in town overnight after hearing Henry's stimulating oratory were more conservative. The two resolutions that Patrick Henry never introduced were especially confrontational to Parliament and King George III:6

- Resolved, That his Majesty’s liege People, the Inhabitants of this Colony, are not bound to yield Obedience to any Law or Ordinance whatever, designed to impose any Taxation whatsoever upon them, other than the Laws and Ordinances of the General Assembly aforesaid.

- Resolved, That any Person, who shall, by speaking or writing, assert or maintain that any Person or Persons, other than the General Assembly of this Colony, have any Right or Power to impose or lay any Taxation on the People here, shall be deemed an Enemy to this his Majesty's Colony.

Governor Francis Fauquier was aware of the two additional resolutions. He wrote back to London:7

- I am informed the gentlemen had two more resolutions in their pocket, but finding the difficulty they had in carrying the 5th which was by a single voice, and knowing them to be more virulent and inflammatory; they did not produce them.

on May 30, 1765, Patrick Henry got the House of Burgesses to pass five resolutions objecting to the Stamp Act

Source: Mary Tucker Magill, History of Virginia for the Use of Schools (1873, p.159)

Governor Fauquier blocked the Virginia Gazette from publishing the resolutions and dissolved the House of Burgesses on June 1, 1765. However, Henry's proposals were widely distributed to newspapers in other colonies. Many printed all seven of the resolutions as if they had been adopted by the Virginia General Assembly. The word spread that Virginia claimed Parliament lacked the power to impose a tax unilaterally.

Fauquier also came personally to the rescue of George Mercer in October, 1765. Mercer planned to start collecting the stamp tax on November 1. Richard Henry Lee, a political enemy of Mercer, arranged for effigies of the tax collector to be burned in protest. When Mercer was accosted by "Gentlemen of property" as he walked near the Capitol, Governor Fauquier personally walked him to safety at the Governor's Palace. Mercer quickly resigned and fled to England, leaving no one in Virginia willing to collect the tax.8

Resistance to the Stamp Act tax was widespread and the colonies chose to work together, in contrast to 1754. Back then, the northern colonies had been forced by English officials to discuss a common response to potential war with the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederation). Joint military action by the colonies was uncommon, and there was no common plan to defend western lands against Native American and French attack. When Governor Dinwiddie was organizing a force in 1754 to capture the French fort at the Forks of the Ohio, only North Carolina had agreed to assist.

The Albany Congress considered a plan of union proposed by Benjamin Franklin for all colonies except for Georgia and Delaware. The seven colonies meeting in Albany, New York in July 1754 agreed to create a Grand Council, to be led by a President General appointed from London. Colonies would elect 48 members based on population. Massachusetts and Virginia would each select seven members, Rhode Island would select two.

After the commissioners returned to their seven colonies, none of them chose to take action on the proposed plan of union. The British military took the lead in dealing with the threats from the French and Native Americans and coordinated actions as needed. The colonies continued to operate as rivals with each other; they did not bond together at Albany and establish an alliance, even when threatened militarily.9

The combined colonial response to the Stamp Act set a new precedent of close inter-colonial cooperation. In 1765, nine colonies selected representatives to a Stamp Act Congress that met in New York.

Virginia was not one of the nine colonies; it sent no one to the Stamp Act Congress. The House of Burgesses had been dissolved by Governor Fauquier on June 1 and could not select delegates, and there was no other mechanism to select people to represent Virginia in New York. In 1765, public elections in Virginia were held only when called by the governor in order to choose members of a new House of Burgesses.

That October 1765 meeting in New York coordinated inter-colonial economic sanctions against Great Britain, hoping to force repeal of the Stamp Act before it went into effect on November 1, 1765. The Stamp Act Congress passed a Declaration of Rights and Grievances that included "no taxes ever have been, or can be constitutionally imposed on them, but by their respective legislatures."

For the first time, a combination of American colonies agreed on a statement in opposition to British policy. Enough colonial merchants agreed to stop importing items from Great Britain to impress manufacturers across the Atlantic Ocean.10

Social pressure increased compliance with non-importation agreements; local committees demanded merchants and wealthy residents stop purchasing British goods. In 1765 almost everyone in the 13 colonies was a loyalist, but the benefits of being part of the British Empire were starting to be questioned.

When Benjamin Franklin was interrogated by Parliament in 1766, he made the case that the colonies had paid a fair share for the costs of the French and Indian War. He stated that the colonists would never accept that a Parliament, with no American representatives, could impose an "internal tax."

Franklin was asked 174 questions during his examination. His responses to two questions provided members of Parliament insight regarding the ability of the British government to use military force to collect taxes:(emphasis added)11

- Q. Can anything less than a military force carry the Stamp Act into execution?

-

- A. I do not see how a military force can be applied to that purpose.

-

- Q. Why may it not?

-

- A. Suppose a military force sent into America: they will find nobody in arms; what are they then to do? They can not force a man to take stamps who chooses to do without them. They will not find a rebellion; they may, indeed, make one.

-

Under the pressure from the business community worried about the loss of profits from colonial trade, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. That brought only temporary relief. The Virginia elite decided over time, starting with the Proclamation of 1763 and the Stamp Act, that continued royal government was too great a threat to their family wealth and political liberty.

Parliament refused to collaborate with the colonies. The concept of a commonwealth of indepedent nations, voluntarily united with Britain, was not realized until after World War I. Instead, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act on March 18, 1766 to assert bluntly that colonial legislators were powerless: 12

- An act for the better securing the dependency of his majesty's dominions in America upon the crown and parliament of Great Britain.

- Whereas several of the houses of representatives in his Majesty's colonies and plantations in America, have of late against law, claimed to themselves, or to the general assemblies of the same, the sole and exclusive right of imposing duties and taxes upon his majesty's subjects in the said colonies and plantations; and have in pursuance of such claim, passed certain votes, resolutions, and orders derogatory to the legislative authority of parliament, and inconsistent with the dependency Of the said colonies and plantations upon the crown of Great Britain : may it therefore please your most excellent Majesty, that it may be declared ; and be it declared by the King's most excellent majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the lords spiritual and temporal, and commons, in this present parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, That the said colonies and plantations in America have been, are, and of right ought to be, subordinate unto, and dependent upon the imperial crown and parliament of Great Britain; and that the King's majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the lords spiritual and temporal, and commons of Great Britain, in parliament assembled, had. bath, and of right ought to have, full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever,

- II. And be it further declared and enacted by the authority aforesaid, That all resolutions, votes, orders, and proceedings, in any of the said colonies or plantations, whereby the power and authority of the parliament of Great Britain, to make laws and statutes as aforesaid, is denied, or drawn into question, arc, and are hereby declared to be, utterly null and void to all in purposes whatsoever.

George Mason suggested soon afterwards that the colonies would not peacefully accept British policy; force would be required. He wrote:13

- We claim Nothing but the Liberty & Privileges of Englishmen, in the same Degree, as if we had still continued among our Brethren in Great Britain: these Rights have not been forfeited by any Act of ours, we can not be deprived of them, without our Consent, but by Violence & Injustice

To make clear that Parliament had the power to implement its declared authority, it punished New York and suspended that colony's elected assembly in 1767. New York had refused to comply with the 1765 Quartering Act, which obligated it to provide housing and supplies to British troops stationed within the colony's borders. Virginia leaders recognized that actions taken against any colony could be taken against Virginia. Parliament was uniting rather than dividing 13 colonies.14

The Townshend Acts, passed in June 1767, began to tax products made in England as well as from other nations. That set a precedent of expanding the Navigation Acts into an internal tax, and triggered riots in Norfolk.

The House of Burgesses sent petitions to London, but arguments and complaints had no impact on Parliament. As Great Britain sought to extract revenue from the colonies to pay for the French and Indian War and implement the mercantilist philosophy, leaders in 13 colonies recognized that British taxation could increase without limits.

Inter-colonial cooperation was not a traditional policy. Virginia had squabbled with other colonies since 1632 over borders and control of land. Even when Native Americans supplied by the French had attacked the western settlements during the French and Indian War, the American colonies had treated each other as rivals who were independently connected to London. Virginia and Pennsylvania had competed over getting the British army to build a road to capture Fort Duquesne, seeking to locate new infrastructure so it would facilitate western settlement and the right of each colony to sell "their" land on the Ohio River.

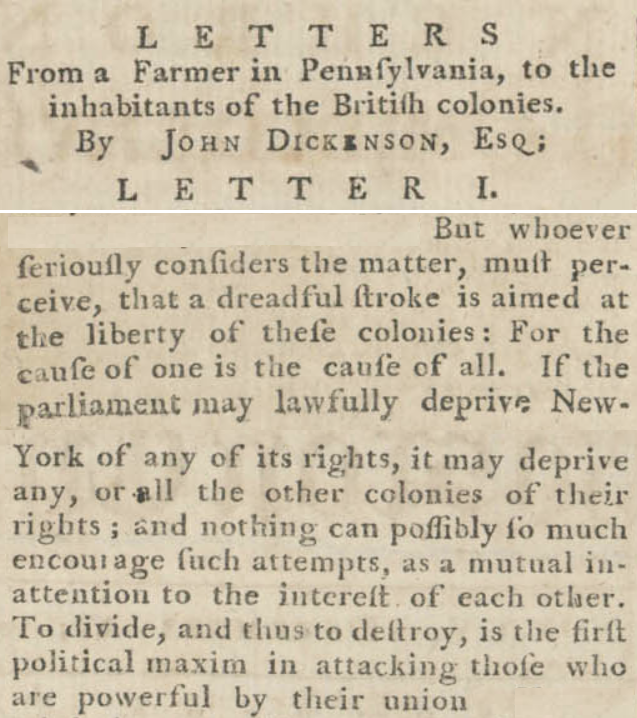

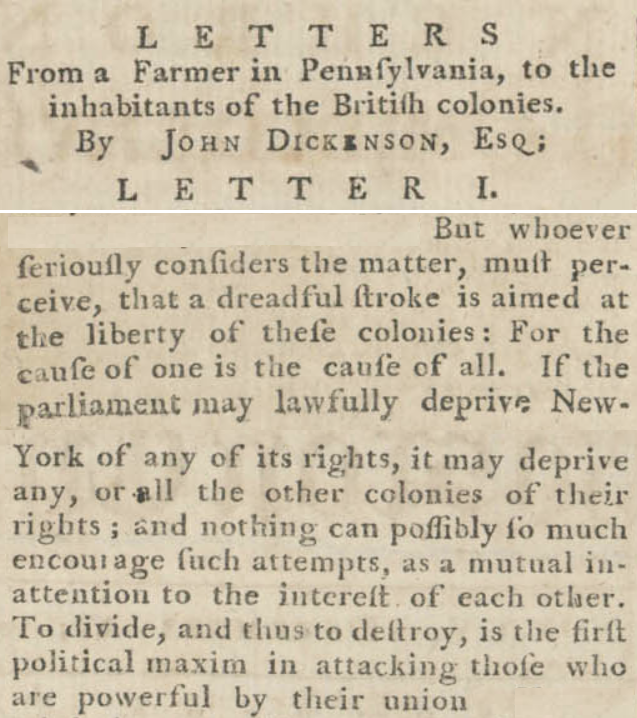

An American identity began to develop as Parliament tried to exert stricter controls in the 1760's. Colonists began to envision themselves as allies dealing with a common threat, such as the creation of vice-admiralty courts without a jury for trials. John Dickenson published "Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies" in December 1767-February 1768. He articulated the perspective that all the colonies needed to work together in opposition to Parliament.

Dickenson wrote in his first letter:15

- ...the cause of one is the cause of all.

leaders in Virginia endorsed John Dickenson's perspective on inter-colonial coordination

Source: Massachusetts Historical Society, Letters From a Farmer in Pennsylvania, to the inhabitants of the British colonies

John Adams thought the American Revolution began in the mid-1760's, long before war broke out, as the colonists changed their minds, hearts, and even religious sentiments. Reflecting upon the topic many years later, he wrote:16

- What do We mean by the Revolution? The War? That was no part of the Revolution. It was only an Effect and Consequence of it. The Revolution was in the Minds of the People, and this was effected, from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen Years before a drop of blood was drawn at Lexington.

On May 16, 1769, the Virginia House of Burgesses approved a measure asserting that it had more authority than Parliament to approve taxes. The elected representatives of the people who could vote claimed:17

- That the sole Right of imposing Taxes on the Inhabitants of this his Majesty's Colony and Dominion of Virginia, is now, and ever hath been, legally and constitutionally vested in the House of Burgesses.

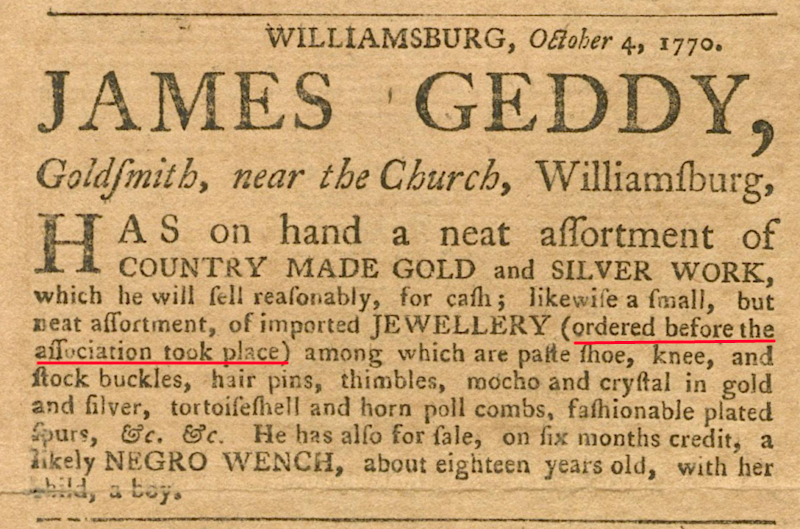

In response the royal governor, Lord Botetourt, dissolved the legislature the next day. The members immediately retired to the Raleigh Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street, just a few yards away from their official chamber in the Capitol building. The now-former burgesses, in a legally-unsanctioned meeting, agreed to organize a non-importation Association. They hoped, like leaders in other colonies, that economic sanctions would generate enough pressure to force a change in British policy. The decision to create the Association was followed by eight toasts; the members were well lubricated with alcohol when they finished their business that day.

The Association agreement was signed on May 17, 1769, and members agreed to stop buying (with some exceptions) imported goods on September 1. Purchases of imported slaves would stop on November 1. The members also agreed to stop killing lambs so sheep could grow to maturity, providing wool that would be spun locally to replace British cloth.

The Townsend Acts were repealed except for the tax on tea. Colonists were not satisfied. In Virginia, the members of the Association approved a new version of the non-importation agreement on June 22, 1770. The new version, which relaxed some restrictions, was made more enforceable. It created county committees to monitor compliance and apply social/economic pressure on violators. Those committees initiated the development of parallel government organizations outside the control of royal officials.

George Washington convinced 267 men in Fairfax County to sign the 1770 version.18

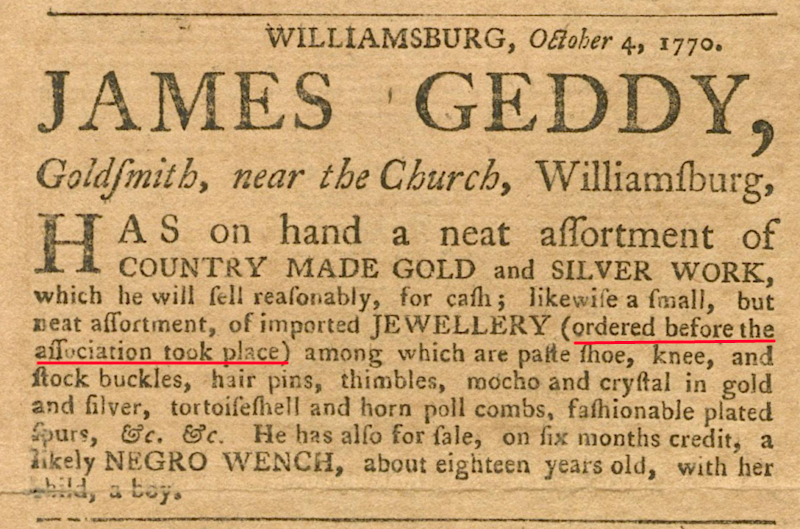

in 1770 a merchant in Williamsburg made sure customers knew he was honoring the non-importation agreement

Source: Library of Congress, George Washington and the "Spirit of Association"

No British troops were stationed in Boston after the end of the French and Indian War, but mob violence changed that. After customs commissioners were attacked in 1768, Major General Thomas Gage sent units from New York and Ireland to Boston to protect royal officials. The Regulars arrived on October 11, 1768. Some managed to get hired for local jobs, putting Boston laborers out of work. Soldiers on patrol at night demanded to know why people were on the streets, and the refusal of Boston residents to answer questions led to regular fistfights.

Keeping soldiers in close proximity with troublemakers led to the "Boston Massacre" on March 5, 1770. That event, as portrayed by American propaganda, exacerbated the perspective that the colonies were being occupied rather than governed. The Regulars were withdrawn from Boston later in 1770.19

In June 1772, the British revenue cutter Gaspee went aground. Radicals in Massachusetts who were angry at the enforcement of laws against smuggling burned the ship. That obviously angered British officials.

Parliament passed the Tea Act on May 10, 1773. The effort to subsidize the East India Company by granting it a monopoly on the sale of tea to North America would have lowered the price of legal tea in the colonies, but enforcement of tax collection by the Royal Navy was strengthened. Smugglers in Massachusetts who made a living in part by supplying the market with untaxed tea, including the merchant John Hancock, recognized that tighter and tighter restrictions on trade would put them out of business.

Americans expressed their objections by boycotting tea. In Boston, an organized mob thinly disguised as Native Americans seized a ship in the harbor on December 16, 1773 and dumped the cargo of tea into the water.

In response to the Boston Tea Party, Parliament chose to punish the rebellious colony. Parliament closed the port of Boston, reduced dramatically the powers of the locally-elected government in Massachusetts, allowed British officials to transport Americans to England for trials far from a jury of peers, and forced the colony's residents to host British soldiers in their homes without pay.

Together, the Boston Port Act, Massachusetts Government Act, Act for the Impartial Administration of Justice, and the Quartering Act became known as the Coercive Acts. A fifth bill extended the boundaries of the Canadian province of Quebec down to the Ohio River. That blocked the claims of various speculators in Virginia to land grants in the Northwest Territory across the Ohio River, and empowered Catholics to hold public offices.20

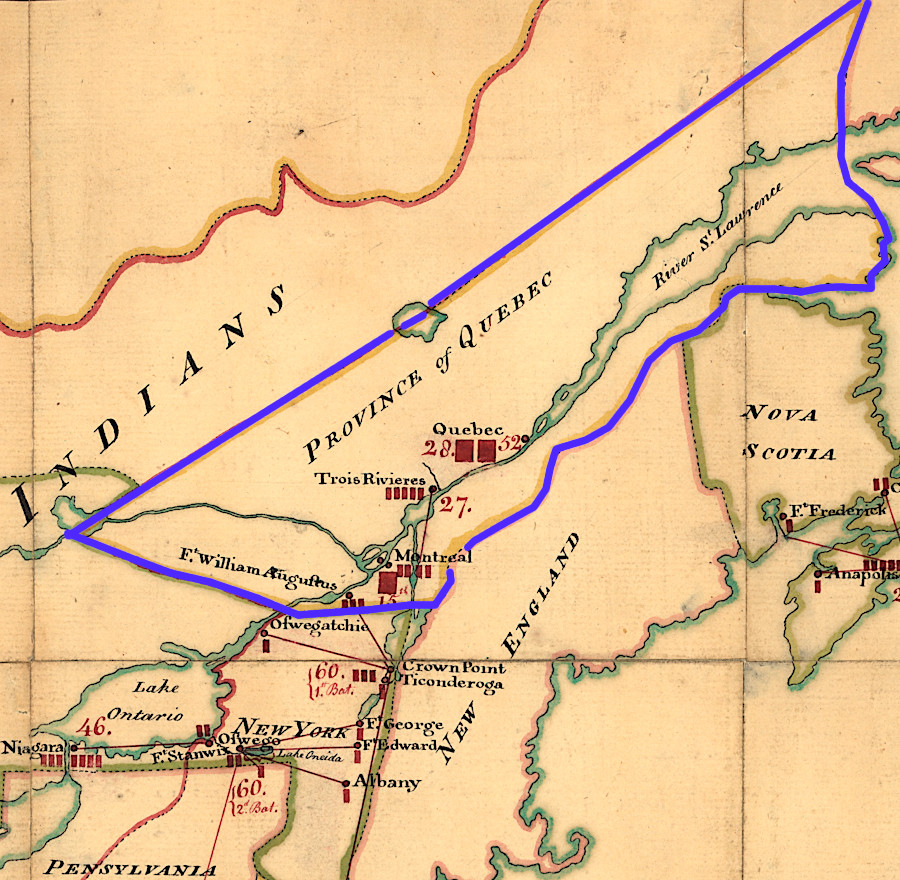

the boundaries of the new English colony of Quebec, established in 1763, were far to the north of western lands claimed by Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Cantonment of the forces in North America 11th. Octr. 1765

Leaders in all 13 colonies were alarmed by the "intolerable" behavior of Parliament. Destruction of the economy and freedoms of Massachusetts residents was clearly a threat to the other 12 colonies. Instead of intimidating the Americans, Parliament's reprisals united them and created a new perspective that all the colonies had overlapping common interests which bonded them to each other more tightly than to Great Britain.

By 1774, Virginia's elite were so dissatisfied with English rule that they chose to conspire with other colonies to establish a resistance movement. Under the refrain of "no taxation without representation," colonists objected to how their economic options were being constrained. An economic recession with high interest rates was triggered by effective British interruption of the illegal colonial trade with the Caribbean islands.

Blocking that trade ended the import of gold and silver coins (specie) from non-British sources into the colonies. Once it was no longer easy to exchange paper currency issued by the colonies into internationally-accepted specie, the value of the colonial paper and the value of colonial land dropped significantly. That led to bankruptcies and political agitation to reduce imports, which required sending gold and silver coins to England for payment:21

- Privateering, smuggling, and military payments brought about French and Indian War prosperity, which led to an ample money supply, low interest rates, and high real estate prices. That, in turn, increased colonial borrowing to buy real estate and imports. The loss of wartime profits coupled with British trade and monetary policy changes, however, caused a rapid decrease in the money supply, and thus high interest rates, low real estate prices, and defaults on loans falling due. That, in turn, meant rampant bankruptcies, which spelled the loss of life, liberty, and property. Attempts to reverse policies or find alternative sources of trade and money met British policy recalcitrance, and thus increased questioning of the efficacy and morality of British rule.

Surprisingly, the leaders of the insurrectionists were the wealthy elite in the colonies who had gained authority and power under the rule of Great Britain. Typically those already in power resist revolutions because they overturn the "establishment." As revolutions disrupt the existing system, the wealth and power of the current elite normally are redistributed as new leaders claim the right to rule based on new authority. Existing leaders may survive incremental change managed by peaceful political procedures, but rapid change in a revolution is often accompanied by the seizure of property and execution of the old elite.

In Virginia, members of the Governor's Council, House of Burgesses, and county courts were at risk of losing their property and potentially even their lives if a new class of rebels took charge in a revolution. As demonstrated in the 1676 Bacon's Rebellion, if top leadership lost control then a new class of people could seize the brick mansions, empty the wine cellars, and oppress the former officials. Particularly in 1774-1776, the existing leaders in Virginia succeeded in the extraordinary challenge of taking charge of a mass effort to replace the authority of the King and Parliament... and remaining in authority when the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783.

King George III and his Privy Council thought that closing the port of Boston after the destruction of East India Company tea would isolate the town from other colonists who feared similar punishment. Rivalries between colonies would prevent united action, Boston would eventually be forced to pay for the tea, and Parliament's power to impose "internal taxes" upon the colonists would be accepted. Economic sanctions were expected to force the colonists to accept the primacy of London and the economic constraints of the mercantilist system, so the profits of the colonies would continue to flow to Great Britain.

The response by other towns in Massachusetts which could have captured shipping traffic from Boston, and from 12 other colonies, was the exact opposite. Colonial leaders recognized that they too could experience the punishments imposed on Boston, and chose to unite in resistance.

The shifting attitude towards acceptance of British authority is reflected by the use of a new term. Those who supported continued acceptance of Parliament's mandates were labeled as "loyalists." That term would have applied to all colonists at the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, but over time a greater percentage adopted an American identity and eventually were labeled "patriots."

To show its solidarity with Massachusetts, on May 14, 1774 the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a resolution calling for a day of "Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer." The day for action was set for June 1, when the closure of the port of Boston went into effect.

Declaring a special day was a confrontational action. Only the Royal Governor had the authority to declare days of fasting and prayer; the House of Burgesses was blatantly asserting it had a power to which it was not entitled. In response, on May 26, 1774 Lord Dunmore dissolved the elected component of the Virginia legislature, the House of Burgesses.

The burgesses remembered their response to Governor Botetourt in 1769. He too had dissolved the legislature after it had passed an in-your-face resolution challenging the authority of Parliament.

In 1769 the burgesses had not gone home. Instead, they had assembled without royal authority and established a non-importation plan to apply economic pressure on businesses in Great Britain. The Virginians anticipated than the loss of sales in the colonial market would impact merchants in Great Britain, and the pressure from merchants would force Parliament to alter its policies. That approach had succeeded after passage of the Stamp Act in 1765, and it was also successful after passage of the Townsend Acts in 1769.

In 1774, the Virginia burgesses decided again that dissolution of the House of Burgesses did not mean the legislators had to go home. They met on May 27, without any royal authority. Once again they chose to gather in the largest private space that was readily available, the Raleigh Tavern.

In another extra-legal meeting comparable to 1769, the 89 burgesses passed resolutions to denounce the closing of the port and called for a continental congress of all colonies:22

- We are further clearly of opinion, that an attack, made on one of our sister colonies, to compel submission to arbitrary taxes, is an attack made on all British America, and threatens ruin to the rights of all, unless the united wisdom of the whole be applied.

By a curious quirk of timing, that same evening there was a ball given in the name of the House of Burgesses at the Governor's Palace to honor Lady Dunmore. Some of the burgesses who had been in the Apollo Room at Raleigh Tavern on the morning of May 27, 1774 also attended the entertainment. They socialized with Governor Dunmore despite their political differences.23

The burgesses issued a call for counties to elect delegates to attend an independent convention, whose members - not the House of Burgesses - would select delegates for a continental assembly. What ended up becoming the First Virginia Convention (of five total conventions by 1776) was not a meeting of the House of Burgesses. County sheriffs who oversaw the election of delegates to attend the First Virginia Convention ignored the fact that those elections were not authorized by Governor Dunmore.

The elections were also a time for some counties to approve resolutions that articulated grievances and called for action against British authority. The Fairfax Resolves, written primarily by George Mason and George Washington, ended up being widely circulated to other colonies and used as a guide to defining American rights. Fairfax County was also the first jurisdiction in Virginia to go the extra step beyond expressing concerns. On September 21, county officials created an independent militia outside the control of the colonial governor.

The First Virginia Convention met in Williamsburg in August, 1774 and selected seven men to attend the "general congress" in Philadelphia. That convention met when Governor Dunmore had left town to fight Shawnee on the western edge of the colony, so there was no direct confrontation.

The royal governor was the official leader of the colonial militia forces in Virginia at the start of the American Revolution. In the second half of 1774, what became known as "Lord Dunmore's War" against the Shawnee was primarily a way to maintain the colony's claims to lands along the Ohio River. The Virginia gentry were vested in land grants to the Ohio Company, and Dunmore saw military action as an opportunity to block Pennsylvania's efforts to control the territory. Success might also build public support for the British government and divert dissatisfied Virginians from pursuing insurrection.

Lord Dunmore spent five months marching to Pittsburgh and moving down the Ohio River, then negotiating the Treaty of Camp Charlotte after his forces reached the edge of the Shawnee towns, before returning to Williamsburg in December, 1774. On January 18, 1775, he hosted a party with members of the still-dissolved House of Burgesses to celebrate the christening of his ninth child (a daughter he named Virginia) at the Governor's Palace. The Royal Governor intended to stay in the colony, convince the unhappy settlers to accept the policies issued by officials in London, and continue to increase his personal wealth.24

His efforts were not successful. While Dunmore was away from Williamsburg dealing with the Shawnee, many in Virginia's House of Burgesses had been radicalized further. Suspicion of British intentions was commonplace. The perception grew that Parliament was never going to revise its approach and adopt policies that were acceptable in North America. The mercantilist philosophy presumed the colonies existed to increase wealth in the mother country. The colonists recognized that Parliament-imposed taxes could be used to constantly drain wealth from America for the benefit of people in London.

The frustration with colonial rule by Britain increased across all the colonies. The most obvious objections were expressed in Massachusetts, but through Committees of Correspondence and newspapers each colony moved further and further away from traditional acceptance of British authority and deference to Parliament.

By the time Lord Dunmore returned from the Ohio River at the end of 1774, a Continental Congress had met in Philadelphia to coordinate an intercolonial approach to the Intolerable (Coercive) Acts. All colonies except Georgia participated. Virginia sent a well-respected delegation and Peyton Randolph, Speaker of the House of Burgesses, was elected president of the Congress. The Massachusetts delegation consciously promoted the visibility of the Virginians, recognizing that joint efforts by the colonies would have more impact. Patrick Henry's proposal to give colonies with larger populations more votes in the decision process generated objections from small colonies such as Rhode Island. In the end, all colonies were give one vote because no one had reliable data on the population of each colony.25

That First Continental Congress in September-October 1774 adopted inter-colonial Articles of Association. They required local enforcement of economic sanctions against Great Britain. The many Committees of Safety in Virginia's counties began creating the political and administrative infrastructure for government independent of royal control almost two years before the Declaration of Independence would be adopted.

On October 25, 1774, the First Continental Congress approved a petition to King George III asking for the Coercive Acts to be repealed. The colonial representatives in that meeting organized a Continental Association to manage a boycott of British goods (including purchase of imported slaves) starting December 1, 1774. A ban on exports, which would cause a dramatic impact on Virginia, was scheduled to start on September 1, 1775.26

Applying economic pressure had been successful in getting the 1765 Stamp Act repealed. The 1774 petition and the boycott had little effect, in contrast to the economic sanctions by colonists in 1765. The alternative to peaceful change was becoming more clear. Colonists who remained supporters of royal authority were beginning to be identified as "loyalists," a term that no longer applied to everyone.

Starting in 1774, the Virginia gentry started to create a parallel system of government outside the control of the royal officials. Governor Dunmore officially controlled the militia, so "independent companies" and Committees of Safety were formed. In Frederick County, Major Adam Stephen wrote on February 1, 1775:27

- ...Lord Dunmore may depend on it, the Militia will never obey his orders again.

Dunmore and his Governor's Council could constrain action by the House of Burgesses, so counties elected representatives to five unauthorized Virginia Conventions that were totally outside the control of British officials.

All ships engaged in trade with Europe and the Caribbean were, at least in theory, officially registered and taxed by official customs agents at Virginia ports. Control of trade was usurped by the Continental Association established in October 1774 by the First Continental Congress, with enforcement of non-importation and non-exportation agreements by locally-organized Committees of Observation. Merchants and those purchasing British goods were intimidated into compliance by social and economic pressure, and by overt threats of violence.

On November 1, 1774, a loyalist in Alexandria was dismayed to hear the public support for the Continental Association just approved in Philadelphia:28

- It is plain proof that the seeds of rebellion are already sown and have taken very deep root, but am in hopes they will be eradicated next summer.

British officials in the colonies and their loyalist supporters were well aware of the activities of the American activists who were organizing resistance to the Coercive Acts. The most overt opposition was in Massachusetts, which was heavily impacted after the port of Boston was closed and the colonial charter was revoked. The militia in various towns near Boston stockpiled gunpowder and weapons, including cannon, in preparation for an armed insurrection.

General Thomas Gage knew that the Massachusetts militia were removing gunpowder stored at the Provincial Powder House in Somerville. The militia claimed that only the locally-purchased gunpowder was removed for safekeeping, and the supply purchased by the colony's officials had been left undisturbed.

On September 1, 1774, the general sent a detachment of 250 soldiers from Boston to seize the remaining royal gunpowder. The troops floated the barrels on boats down the Mystic River to Boston, along with two cannon picked up in Cambridge.

Rumors spread that the soldiers had stolen locally-owned gunpowder and fired on local residents. The "Powder Alarm" triggered 4,000 mem to converge at Cambridge, prepared to fight the British regulars if necessary. The Powder Alarm ended up being a dress rehearsal for Lexington and Concord over six months later.

On October 20, 1774, King George III blocked shipments of guns and ammunition to the colonies. The Earl of Dartmouth directed the colonial governors to intercept any shipment to the colonists. Officials in London were preparing to block an armed rebellion by the American colonists.

Nearly all gunpowder in North America was manufactured in England after the French and Indian War; the only gunpowder mill in the colonies in 1775 was the Frankford Mill in Pennsylvania. Colonists knew how to make gunpowder from saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal, but the manufacturing process was not simple. In addition, England had access to cheap saltpeter from India. It was cost effective to let facilities in England acquire ingredients with reliable quality, then combine them in the appropriate percentages and create powder grains of the correct size for different weapons.

If the new policy was effectively implemented, the militia in each colony would become useless. On the western edge of the colonies, traders would lose the most valuable product for doing business with the Native Americans and settlers would lose the ability to defend themselves.

After news of the ban on powder and guns spread, colonists in Rhode Island raided Fort George in Newport and on December 9 stole the cannon and gunpowder there. The colony's governor, who was elected rather than appointed by King George III, bluntly told a Royal Navy captain that the weapons were needed "to defend themselves against any power that shall offer to molest them."

In Connecticut, colonists removed the cannons at the royal battery in New London and carried them further inland on December 13. A day later in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, colonists took away at least 200 barrels of gunpowder from Fort William and Mary. There wee only six British invalids guarding that fort, but they recognized they were under attack and fired cannon at the boats coming to seize the military supplies. No one was killed, so the incident did not trigger a major response within the colonies.

The militia in those four northern colonies were clearly preparing for action against the British Army. That army was large, well-equipped, and organized enough to win any battle with colonial militia. In addition, Great Britain had the largest navy in the world. Colonists preparing for a war in 1774 had little chance of military victory, but collecting powder and cannon would enable defensive operations that might deter the Regulars from attacking towns.29

In February 1775, Fairfax County reorganized its independent militia without any authority from Lord Dunmore. All men between the ages of 18-50 were to be organized into companies of 68 men. They were ordered to obtain a "good Fire-lock in proper Order" and a supply of gunpowder, shot, gun flints, a bullet mold for making more shot, and a cartouch box or powder horn. To pay for the militia, the county imposed a three-shilling tax on all titheables.30

The Second Virginia Convention met in Richmond on March 20-27, 1775 in the Henrico Parish Church (later renamed St. John's Church). New delegates were not elected; Peyton Randolph simply invited those from the First Virginia Convention to attend. The convention selected seven delegates to attend the Second Continental Congress.

The delegates avoided meeting in Williamsburg, where Governor Dunmore might personally try to prevent the assembly backed up by British marines from the warships in the Chesapeake Bay. Richmond was safe because there were not enough marines to march inland and disrupt the meeting. The militia colonels in Virginia counties, appointed by the governor, were not willing to take orders from Dunmore. Instead, they were assisting the local Committees of Safety to enforce the Continental Association to block imports from Great Britain and apply economic pressure on Parliament.

The 120 or so Second Virginia Convention delegates recognized that they had no military capacity to defeat the army and navy of Great Britain, and some delegates considered the talk of preparing for a military confrontation to reflect "the bravery of madmen."

Great Britain had become the world's dominant superpower after winning the Seven Year's War/French and Indian War in 1763. Of the 8,000,000 people living in Great Britain, there were 800,000 men suitable for military service. The American colonies had a population of only 2,500,000, of whom 500,000 were enslaved. In Virginia, 40% of the 250,000 residents were enslaved31

The delegates at the Second Virginia Convention in St. John's Church were energized from a fiery "give me liberty or give me death" speech by Patrick Henry. Henry was becoming a member of the wealthy elite who benefitted from the colonial system, but was also a rabble rousing activist. His eloquence helped unite those white men with the ability to vote in Virginia to start opposing royal power.

The convention decided to put Virginia "into a posture of Defence." The colonial law authorizing county militias had expired and was not renewed before Governor Dunmore dissolved the House of Burgesses in May, 1774. The Second Virginia Convention assumed the power of the colonial legislature and authorized creating military forces that would be outside the control of Governor Dunmore. A 12-man committee was created to guide the actions of the independent companies established in several counties, but no colony-wide units were created.32

Like General Gage further north, Governor Dunmore was aware of the activities of resistance leaders in Virginia. He knew that the illegal, illegitimate militias known as Independent Companies were being formed.

While Richmond was a safe location for a meeting, Lord Dunmore had an effective tool to punish colonial leaders. He proposed to invalidate the surveys made along the Kanawha and Ohio rivers by William Crawford for parcels to be awarded to soldiers who had enlisted in the Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War. George Washington and other members of the gentry had acquired many of the military warrants issued to veterans, and Crawford had started surveying in 1770. Dunmore contended that Crawford had not been licensed properly. George Washington personally had 23,000 acres of land claims at risk.33

In Massachusetts, General Thomas Gage had send a detachment on Feb. 25, 1775 to seize cannon stockpiled in Salem. The militia blocked the soldiers under Colonel Alexander Leslie from crossing the drawbridge leading into town. The standoff was resolved without violence when a deal was negotiated. The drawbridge was lowered, Leslie's troops marched across to comply with his orders to go to Salem, and then British returned back to Boston without searching the town.34

Gage made another attempt on April 19, 1775 to seize cannons and military supplies. Gage may have been trying to retrieve four brass cannon that had been stolen from the Old Gun House and the New Gun House on Boston Common. He was embarrassed that the cannon had been removed despite his orders to have the buildings guarded, and did not notify London officials of the theft. Gage chose to send troops to Concord after learning from spies that the four brass cannon were there, apparently hoping to retrieve them before having to admit that his military preparations had been inadequate.36

The effort to take control over military supplies at Concord required marching through the town of Lexington. The community's militia company blocked the way.

No one knows who fired first and started the shooting war at Lexington, in which eight of the militia were killed and 10 wounded. As historian Rick Atkinson has noted, on that day 75,000 rounds were fired by 4,000 Massachusetts militia at 800 British troops. Out of every 300 shots fired, only one hit a British soldier.

Atkinson surmises that at Lexington:36

- ...the shot heard around the world probably missed.

Virginia newspapers reported in events in northern colonies and London. Delivery of the news was delayed by weeks and even months as ships sailed through the Atlantic Ocean. No one in Williamsburg was aware of the fighting at Lexington and Concord when, two days later, Lord Dunmore implemented similar orders from London to seize military supplies in the Virginia colony.

Separation from Great Britain was part of many private conversations starting in 1774, but the first public call by a governmental body for independence did not occur until April 22, 1776. On that date, the Cumberland County Committee for Safety in Virginia passed a resolution and issued direction to the county's delegates at the Second Virginia Convention:37

- We therefore, your constituents, instruct you positively to declare for an Independency, that you solemnly abjure any allegiance to His Britannic Majesty and bid him a good night forever...

In April 1775, residents in Williamsburg appointed guards to protect the brick Magazine where the colony's muskets and gunpowder were stored. On the very windy night of April 20, 1775, the volunteer watchers abandoned their posts.

Dunmore took advantage of that opportunity. He had 20 sailors and marines from the schooner HMS Magdalen land at Burwell's Ferry near the modern Kingsmill Resort. They walked four miles to Williamsburg before dawn on April 21, opened the locked gates of the magazine using keys provided by Lord Dunmore, and removed the half-barrels of gunpowder weighing 65 pounds each.

marines from the HMS Magdalen marched from Burwell's Ferry to Williamsburg and seized half-kegs of gunpowder in the Magazine

Source: Library of Congress, Armée de Rochambeau, 1782. Carte des environs de Williamsburg en Virginie où les armées françoise et américaine ont campés en Septembre 1781 (by Jean Nicolas Desandrouins, 1782)

Dunmore justified his seizure of 15 barrels of the colony's gunpowder by referencing the rebellious activities of the Virginians, particularly because:38

- ...dangerous measures... against the Government, which they have now entirely overturned, and particularly their having come to a resolution of raising a body of armed Men in all the counties, made me think it prudent to remove some Gunpowder which was in a Magazine in this place, where it lay exposed to any attempt that might be made to seize it, and I have reason to believe the people intended to take that step.

the Magazine in Williamsburg stored gunpowder, which Lord Dunmore removed in April 1775

The governor also made a specious claim that he was ensuring a slave insurrection could not use the gunpowder, but the colonists recognized he was disarming them. Local residents quickly discovered what was happening but could not organize an effective response. The sailors and marines had time to load 15 of the 18 half-barrels into a wagon and return safely to the Magdalen.

Virginians were outraged. Patrick Henry led militia from Hanover on an unauthorized march towards the capital city. The governor's physical safety was at risk.

Peyton Randolph, Speaker of the House of Burgesses, arranged for the protests about removal of gunpowder from the magazine at Williamsburg to be resolved peacefully. Violence at Williamsburg was avoided by a face-saving compromise when the royal Receiver General paid for the value of the gunpowder.

Dunmore's attempt to seize the gunpowder was in response to orders sent from London to all the colonial governors to control the military supplies that might be used if the political debate in the colonies into a shooting war. Rebellious activists in both Massachusetts and Virginia anticipated efforts to seize military supplies.39

There were efforts by Parliament to compromise and maintain peace with the colonies. They started before the fighting at Lexington and Concord, and continued into 1778.

In February 1775, Prime Minister Lord North arranged for Parliament pass a Conciliatory Proposal to restore the relationship with the colonies. Parliament agreed that if a colony agreed to tax itself an adequate amount to pay for the common defense and the costs of colonial government, Parliament would not impose taxes other than the traditional fees used to regulate commerce.

From London's perspective, that proposal was "conciliatory." In particular, it addressed the issue on internal taxes such as the Stamp Act by agreeing that the colonies would control such taxes.

Americans were aware that the proposal finally approved by the House of Commons was a far weaker version of a bill that Lord Chatham (William Pitt) had introduced, but the House of Lords had rejected. Pitt also had proposed completely repealing the Coercive Acts punishing Massachusetts and 1774 Quebec Act, acknowledging the Continental Congress, and guaranteeing trial by jury within the colonies.

Most significantly, Pitt's bill said the colonies could not be taxed except with their consent. In exchange, the colonies would have to agree that they would accept a British force stationed within them.

From the colonial perspective, Lord North's proposal was unacceptable. While only the colonies would be allowed to raise taxes for defense, the proposal said Parliament would determine if the amount of taxes was sufficient to cover costs. If not, the colonies would be obligated by Parliament to raise even more money. Each colony could use whatever form of taxation it preferred to increase the total revenue, but the final level of taxes would be decided by people living across the Atlantic Ocean who had not been elected and who could not be replaced by American voters.

Because men in London would retain ultimate power to set the level of taxation, the colonies would still be dependent upon the whim of Parliament. Lord North's conciliatory proposal failed to protect the colonies from excessive taxation.40

Lord Dunmore called the Virginia House of Burgesses into session on June 1, 1775 to get an official response to Parliament's Conciliatory Resolution. The governor had prorogued the legislature on May 26, 1774 after it had passed a resolution objecting to the Coercive Acts imposed upon Massachusetts. The governor had then traveled to the Ohio River and conducted a war against the Shawnee in the last half of 1774. He mobilized troops for Dunmore's War without recalling the House of Burgesses to raise taxes in order to pay the soldiers, and successfully forced the Shawnee to cede control of Kentucky.

Dunmore's military success had not resolved the question of taxation without representation. He recognized that his "loyal" subjects also were on the verge of committing violence. The shooting war that had erupted in Massachusetts on April 19, and been avoided in Williamsburg when the gunpowder was seized, could erupt in Virginia if there was another incident. Governor Dunmore asked the House of Burgesses to support the Conciliatory Proposal as a last-ditch opportunity to prevent open conflict. That would be the first General Assembly since May 1774. The governor had postponed other meetings that were planned after he returned from the Ohio River in December.

Because Lord Dunmore had prorogued rather than dissolved the last meeting of the House of Burgesses, no new elections were required to select the burgesses who gathered at the Capitol on June 1, 1775. An election for a

new House of Burgesses would have permitted county sheriffs to arrange a simultaneous vote for choosing official delegates to a Continental Congress.

Many of the burgesses had attended the Second Virginia Convention in April; they were playing the roles of both official and unofficial leaders. Peyton Randolph returned from Philadelphia, where he was serving as President of the Second Continental Congress, to be Speaker of the House of Burgesses again.

The House of Burgesses recognized Lord North's proposal as a scheme to divide Americans. Lord North had addressed only the tax issue, provided no relief to Massachusetts, and continued to block legal settlement of claims in western lands that had been transferred to the colony of Quebec in 1774.

The Conciliatory Proposal was a divide-and-conquer approach sent separately to the 13 individual colonies. That tactic was designed to break the Continental Association established in 1775 for a united non-importation agreement, and prevent the 13 rebellious colonies from coordinating an effective joint response to British tax policies. Lord North had passed a Conciliatory Proposal, but refused to acknowledge the Continental Congress as a legitimate representative body which could negotiate a response.

Parliament mistakenly thought most Americans were committed loyalists, and the other colonies could be prevented from supporting the rebels who were fomenting insurrection in Massachusetts. Parliament had passed the Coercive Acts intending to create fear of a retaliatory response that might damage other colonies, comparable to closure of the port at Boston. The Conciliatory Response, passed later, was a last-ditch effort by members of Parliament who opposed the use of force.

The colonial governors provided inaccurate and incomplete perspective to the Secretary of State for the American Colonies and other officials in London. At the same time, few leaders in London traveled personally to the colonies to gain an independent understanding of issues and concerns. Merchants squeezed the Virginia gentry, sinking them so deep in debt that the plantation owners recognized their economic situation was unsustainable; something had to change.

Based on flawed intelligence and understanding of the American concerns, British policies from 1765-1775 exacerbated rather than healed divisions. Colonists who were once all loyalists determined that their economic and social interests were threatened by the King and Parliament. When those colonists sought a redress of their grievances, the response was passage of Coercive Acts and the arrival of more British regiments to assert control.

From a military perspective, Britain was prepared for a fight with the colonists. Canada provided reliable bases, especially for the Royal Navy at Halifax. Forts on the Hudson River at Ticonderoga and Crown Point would allow the Regulars and Royal Navy to isolate the northern colonies from support from Pennsylvania and Virginia. Troops in Boston could seize military supplies at places like Lexington and Concord, so any uprising by the colonial militia could be suppressed.

The fundamental flaw in British thinking was that the colonists would riot and be rebellious, but would eventually accept that resistance against British dominance was unrealistic. A series of small incidents demonstrated that even as far south as Virginia, colonial frustration with British policy could boil over into open rebellion.

Three local men broke into the Magazine at Williamsburg on the night of June 3. Two were injured when they tripped a wire and a shotgun "contraption" fired bird shot pellets. After that event, armed militia began patrolling the city streets. Colonists began plotting to kidnap Lord Dunmore; some feared that he might assassinate Virginia's leaders.

After seeing the reaction to the June 3 event, Lord Dunmore feared someone like Patrick Henry (who had gone to Philadelphia to represent Virginia in the Continental Congress that started on May 10) would organize an angry local response or mobilize militia from other counties to march on Williamsburg. By arranging for the shotgun that wounding two men on June 3, Dunmore had soured the opportunity for compromise.41

The reports of armed conflict at Lexngton and Concord reached Virginia on April 29. On May 1, Dunmore sent his family to safety on the HMS Fowey. He fortified the Governor's Palace, placing swivel guns at the windows and cutting loopholes for firing muskets at any approaching mob. Under political pressure, the local contractor stopped supplying supplies to the British ships in the York River. Acquisition of food and fresh water afterwards was done "by Stealth."

Just six months after leading an army to defeat the Shawnee and being celebrated by members of the House of Burgesses upon his return, Dunmore reported:42

- ...ever in the Place where I live Drums are beating and Men in uniform dresses with Arms are continually in the Streets, which my Authority is no longer able to prevent.

Lady Dunmore and her children returned to the Governor's Palace on May 12.43

By June 1776, Governor Dunmore had moved along with his family to the HMS Fowey in the York River for his personal safety. Virginia militia converted the Capitol into a barracks and used the public park outside the Governor's Palace for cavalry horses. Mobs broke into the Governor's Palace, which was traditionally used as an armory, and stole weapons from the walls.

On June 7 Dunmore went ashore and had dinner at Porto Bello, his hunting lodge six miles from Williamsburg on the road to Yorktown. By 5:00am on June 8, he was climbing on board the HMS Magdalen after fleeing for his life.

He wrote on June 12 that the servants had warned him an armed group was approaching from Williamsburg:44

- Just time to get into our boat and to escape; two men, Carpenters of the Ship, whom we had brought with us in order to cut down a mast for a boat, and who were at a little distance from my house, were Seized by these people, upon my own land, and have been made prisoners, and are now confined in Williamsburg under a guard, a Servant, who got into a Canoe to follow me, a very little time afterwards, was fired at four or five different times.

Lord Dunmore fled from his hunting retreat at Porto Bellow to HMS Fowey, getting onto the warship at 5:00am on June 8

Source: Library of Congress, Armée de Rochambeau, 1782. Carte des environs de Williamsburg en Virginie où les armées françoise et américaine ont campés en Septembre 1781 (by Jean Nicolas Desandrouins, 1782)

The Governor's Council and the House of Burgesses prepared a joint address to the royal governor, inviting him to return to Williamsburg. He replied that the colony's leaders should demonstrate their commitment to support his authority by re-opening the county courts so civil transactions could be completed and laws could be enforced, disarming the independent companies, returning the weapons stolen from the Governor's Palace, and "abolishing that spirit of persecution" which oppressed those loyal to royal government.

He also invited the Governor's Council and the House of Burgesses to come to Yorktown to meet with him, and said:45

- With respect to your entreaty that I should return to the palace, as the most likely means of quieting the minds of the people, I must represent to you, that, unless there be among you a sincere and active desire to seize this opportunity, now offered to you by Parliament, of establishing the freedom of your country upon a fixed and known foundation, and of uniting yourselves with your fellow subjects of Great Britain in one common bond of interest, and mutual assistance, my return to Williamsburg would be as fruitless to the people, as, possibly, it might be dangerous to myself.

The flight of Dunmore from the capital marks the moment when royal authority in the colony ended, though he attempted to exert it for 14 more months.

Lord Dunmore fled Williamsburg on June 8, 1775 and took refuge on a British warship, the H.M.S. Fowey

Source: Library of Congress, Flight of Lord Dunmore

Fighting had not started yet in Virginia when Dunmore left Williamsburg, but the Massachusetts militia were already engaging with British Regulars around Boston. On June 14, two months after open warfare began at Lexington and Concord, the Continental Congress created a national army. A day later, the delegates chose George Washington to organize the Continental Army and lead it.

The willingness of American colonists to fight was demonstrated when both Massachusetts and Connecticut sent troops westward to capture Fort Ticonderoga at the confluence of Lake George and Lake Champlain. That fort, with only 45 British soldiers, surrendered without a shot on May 10, 1775. The colonists captured a major military arsenal, including 78 cannon.46

In contrast to the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775 (11 days after Lord Dunmore fled onto a warship) was bloody. Americans had dug trenches and fortified the hill, threatening to use cannon to shell the British inside Boston and force them to evacuate. In the attack on Bunker Hill, British troops suffered 1,000 casualties. The insurrection was clearly not just a mob that could be dispersed easily.

General Gage lacked the troops that would be needed to march into the countryside, seize military supplies that had been stockpiled at places like Lexington and Concord, occupy the towns, and force acceptance of royal authority in Massachusetts. In response to Bunker Hill, Parliament rejected "conciliation" and doubled down on his approach of the Coercive/Intolerable Acts. It authorized an expansion of the army, including hiring troops from foreign powers, and sent a powerful military force to conquer the rebels.

Even after Bunker Hill, it was not obvious that a general inter-colonial revolution was underway rather than just isolated actions by radicals. For another year, political leaders in America continued to envision British officials changing their policies so the 13 colonies could remain within the British empire.

Links

References

1. Jan Eloranta, Jeremy Land, "Hollow Victory? Britain's Public Debt And The Seven Years' War," Essays in Economic & Business History, Volume XXIX (2011), p.103, p.110, https://www.ebhsoc.org/journal/index.php/ebhs/article/download/215/198/431 (last checked May 23, 2025)

2. "The Sugar Act," The Coming of the American Revolution: 1764 to 1776, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/revolution/sugar.php (last checked July 14, 2025)

3. "Williamsburg Again Has an R. Charlton's Coffeehouse," Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Winter 2010, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Winter10/coffeehouse.cfm; "Patrick Hery's Resolutions Against the Stamp Act," Red Hill: Patrick Henry National Memorial, https://www.redhill.org/primary-sources/patrick-henrys-resolutions-against-the-stamp-act/ (last checked September 1, 2025)

4. "To Benjamin Franklin from Joseph Galloway, 18 [July] 1765," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-12-02-0111 (last checked July 8, 2025)

5. "Patrick Henry’s Resolutions Against the Stamp Act," Red Hill, Patrick Henry National Memorial, https://www.redhill.org/speeches-writings/patrick-henrys-resolutions-against-the-stamp-act/; "Virginia Resolutions 'of an extraordinary Nature' in Newport," Boston 1775 blog, June 24, 2025, https://boston1775.blogspot.com/2015/06/virginia-resolutionsof-extraordinary.html; "Virginia Resolves on the Stamp Act (1765)," Encyclopedia Virginia, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/virginia-resolves-on-the-stamp-act-1765/; "Dispatch from 1765: Stamp Act protest prompts House speaker to accuse new legislator Patrick Henry of treason," Cardinal News, February 13, 2024, https://cardinalnews.org/2024/02/13/dispatch-from-1765-stamp-act-protest-prompts-house-speaker-to-accuse-new-legislator-patrick-henry-of-treason/ (last checked April 18, 2025)

6. "Virginia Resolves on the Stamp Act (1765)," Encyclopedia Virginia, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/virginia-resolves-on-the-stamp-act-1765/; "Virginia Resolutions 'of an extraordinary Nature' in Newport," Boston 1775 blog, June 24, 2025, https://boston1775.blogspot.com/2015/06/virginia-resolutionsof-extraordinary.html; (last checked April 18, 2025)

7. "Virginia Takes an Even Less Firm Stand Against the Stamp Act," Boston 1775 blog, May 31, 2015, https://boston1775.blogspot.com/2015/05/virginia-takes-even-less-firm-stand.html (last checked April 18, 2025)

8. John Kolp and Dictionary of Virginia Biography, "Francis Fauquier (bap. 1703–1768)," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, December 7, 2020, ,/a>; "Francis Fauquier (1703-1768)," The American Revolution, https://ouramericanrevolution.org/index.cfm/people/view/pp0010; "Francis Fauquier (1703-1768)," The American Revolution, https://ouramericanrevolution.org/index.cfm/people/view/pp0010 (last checked July 8, 2025)

9. "Reasons and Motives for the Albany Plan of Union, [July 1754]," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-05-02-0109; "Albany Plan of Union, 1754," Office of the Historian, US Congress, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/albany-plan (last checked June 30, 2025)

10. "Britain Begins Taxing the Colonies: The Sugar & Stamp Acts," National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/sugar-and-stamp-acts.htm; "Anger and Opposition to the Stamp Act," National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/anger-and-opposition-to-the-stamp-act.htm; "The Stamp Act, 1765," Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/stamp-act-1765; "On this day: 'No taxation without representation!'," National Constitution Center, October 7, 2022, https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/no-taxation-without-representation; "Resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress October 19, 1765," Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/resolutions-of-the-stamp-act-congress-2/ (last checked July 8, 2025)

11. "Examination before the Committee of the Whole of the House of Commons, 13 February 1766," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-13-02-0035 (last checked June 24, 2025)

12. "British Commonwealth of Nations (1931)," Making Britain, The Open University., https://www5.open.ac.uk/research-projects/making-britain/content/british-commonwealth-nations-1931; "Great Britain : Parliament - The Declaratory Act; March 18, 1766," The Avalon Project, Yale University, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/declaratory_act_1766.asp (last checked July 14, 2025)

13. "George Mason to the Committee of Merchants in London (June 6, 1766)," ConSource, https://www.consource.org/document/george-mason-to-the-committee-of-merchants-in-london-1766-6-6/ (last checked July 14, 2025)

14. Michael Cecere, Great Things Are Expected From the Virginians, Heritage Books, 2008, p.10, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Great_Things_are_Expected_from_the_Virgi/P9DCwAEACAAJ (last checked July 14, 2025)

15. "Letters From a Farmer in Pennsylvania," Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs, https://history.delaware.gov/john-dickinson-plantation/dickinsonletters/pennsylvania-farmer-letters/; "Virginia's House of Burgesses criticizes taxation without representation," History.com, November 13, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/may-16/virginia-criticizes-taxation-without-representation (last checked July 14, 2025)

16. "From John Adams to Hezekiah Niles, 13 February 1818," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-6854; "John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, 24 August 1815," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-08-02-0560 (last checked July 16, 2025)

17. "Resolves of the House of Burgesses, Passed the 16th of May, 1769," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/3808hpr-db844a7128cc178/ 9last checked July 14, 2025)

18. "Francis Fauquier (1703-1768)," The American Revolution, https://ouramericanrevolution.org/index.cfm/people/view/pp0010; "Virginia Nonimportation Resolutions, 17 May 1769," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0019; "Virginia Nonimportation Resolutions, 22 June 1770," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0032; "Virginia's House of Burgesses criticizes taxation without representation," History.com, November 13, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/may-16/virginia-criticizes-taxation-without-representation; Julie Miller, "George Washington and the 'Spirit of Association'," September 5, 2024, Library of Congress blog, https://blogs.loc.gov/manuscripts/2024/09/george-washington-and-the-spirit-of-association/ (last checked July 14, 2025)

19. "The British Army in Boston," American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/british-army-boston; "The Occupation of 1768 and the Threat to Boston," Old North Church., https://www.oldnorth.com/blog/the-occupation-of-boston/ (last checked July 14, 2025)

20. "The Coercive (Intolerable) Acts of 1774," Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/the-coercive-intolerable-acts-of-1774

(last checked November 14, 2024)

21. Robert E. Wright, "Cruel Bedlam: Bankruptcies and the Break with Britian," Journal of the American Revolution, November 14, 2024, https://allthingsliberty.com/2024/11/cruel-bedlam-bankruptcies-and-the-break-with-britian/; "Virginia's House of Burgesses criticizes taxation without representation," History.com, November 13, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/may-16/virginia-criticizes-taxation-without-representation (last checked July 14, 2025)

22. John Gilbert McCurdy, "Causes of the American Revolution in Virginia," Encyclopedia Virginia, November 12, 2024, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/causes-of-the-american-revolution-in-virginia/; "Association of Members of the Late House of Burgesses, 27 May 1774," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0083; "Dunmore's Dissolution of the House of Burgesses," Colonial Williamsburg, May 23, 2024, https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/discover/moments-in-history/the-tea-crisis/dunmores-dissolution-of-the-house-of-burgesses/ (last checked September 1, 2025)

23. "Dispatch from 1769: Governor dissolves House of Burgesses; Virginia vows boycott of British goods," Cardinal News, May 14, 2024, https://cardinalnews.org/2024/05/14/dispatch-from-1769-governor-dissolves-house-of-burgesses-virginia-vows-boycott-of-british-goods/ (last checked July 14, 2025)

24. "A Revolutionary Spring: 1775," Virginia Museum of History and Culture, Winter/Spring 2025, https://issuu.com/virginiamagazine/docs/virginia_history_culture_-_winter_spring_2025/4; "The First Virginia Convention," Colonial Williamsburg, July 31, 2024, https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/discover/moments-in-history/road-to-independence/the-first-virginia-convention/; "Fairfax Resolves," Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/george-washington-papers/articles-and-essays/fairfax-resolves/; Michael Cecere, Great Things Are Expected FRom the Virginians, Heritage Books, 2008, pp.30-31, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Great_Things_are_Expected_from_the_Virgi/P9DCwAEACAAJ (last checked July 14, 2025)

25. Michael Cecere, Great Things Are Expected From the Virginians, Heritage Books, 2008, p.28, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Great_Things_are_Expected_from_the_Virgi/P9DCwAEACAAJ (last checked July 14, 2025)

26. Michael Cecere, Great Things Are Expected FRom the Virginians, Heritage Books, 2008, p.29, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Great_Things_are_Expected_from_the_Virgi/P9DCwAEACAAJ; "Continental Association, 20 October 1774," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0094 (last checked July 14, 2025)

27. "Major Adam Stewphen to Richard Henry Lee," February 1, 1775, in Naval Documents of the American Revolution - Volume 1, p.77, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/research/publications/naval-documents-of-the-american-revolution/NDARVolume1.pdf (last checked August 30, 2025)

28. "The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777," The Dial Press, 1924, p.44=45, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924013972009 (last checked July 14, 2025)