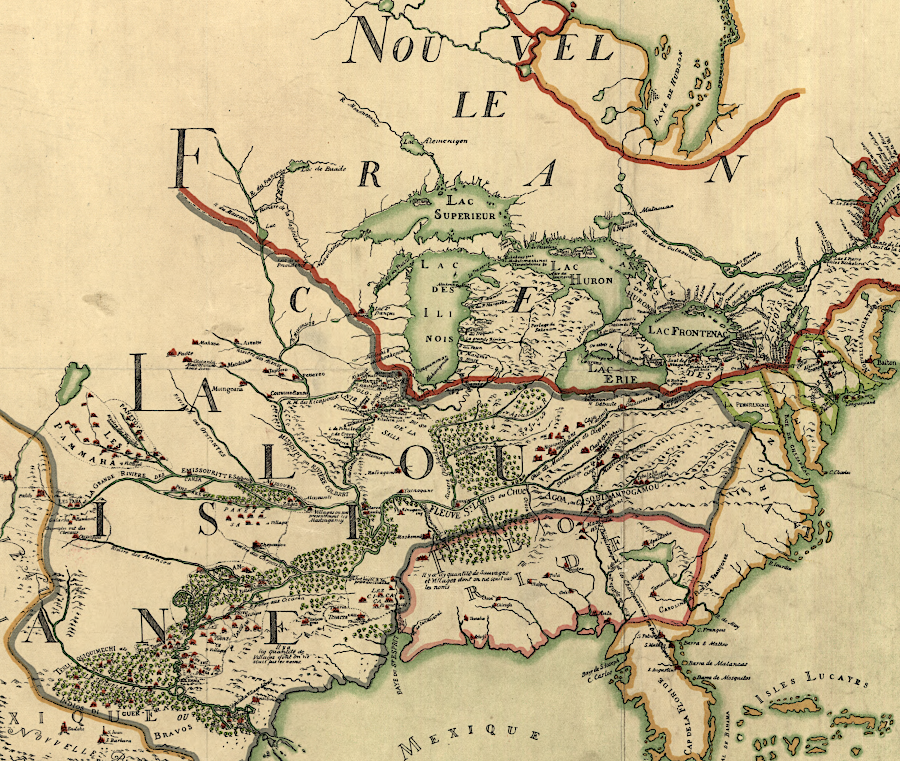

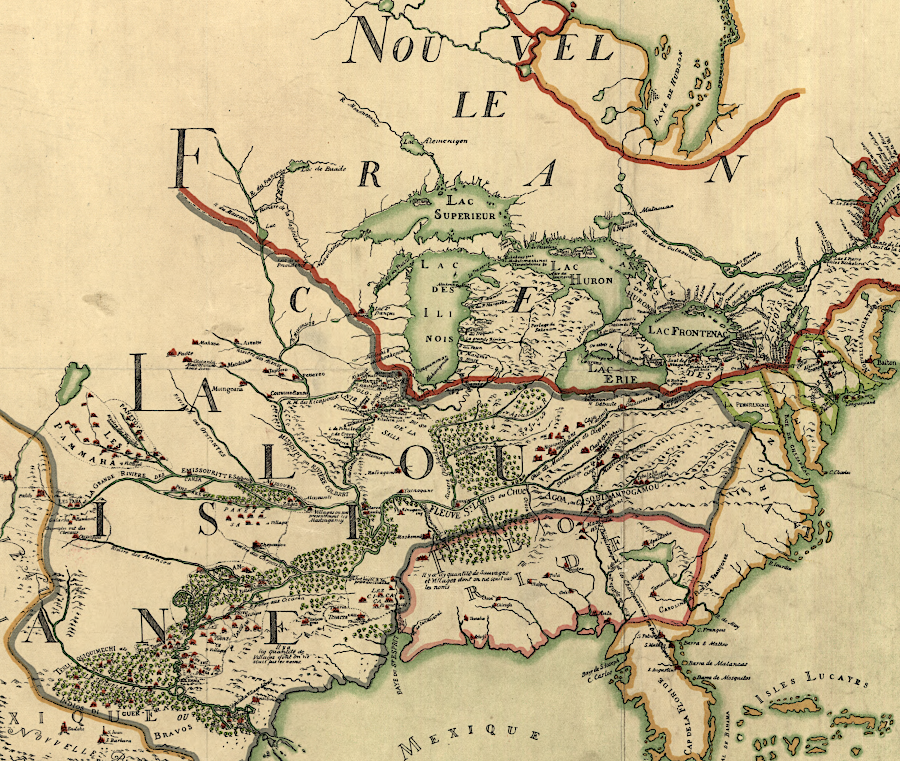

the French claimed Louisiana extended to the Allegheny Front, so English settlers were desired in the backcountry

Source: Library of Congress, Franquelin's map of Louisiana (by Jean Baptiste Louis Franquelin, 1896)

the French claimed Louisiana extended to the Allegheny Front, so English settlers were desired in the backcountry

Source: Library of Congress, Franquelin's map of Louisiana (by Jean Baptiste Louis Franquelin, 1896)

The opportunity to own land was the primary attraction for colonists to risk a trip across the Atlantic Ocean to the colony in Virginia in the Seventeenth Century. In England, social and economic mobility was limited. Few of the farmworkers had an opportunity to acquire land and enter the gentry class.

In Virginia, social and economic barriers were far lower. Once tobacco farming became the primary source of wealth, there was a surplus of land and a shortage of labor. Virginia's leaders sought to attract immigrants by offering cheap land. In addition to the "headright" system established in 1618 and he "treasury" rights for direct sale of land starting in ____, from 1630 to the Revolutionary War the colonial government also offered land grants to those willing to serve in the militia and fortify the frontier.1

Library of Virginia, "Colonial Wars Bounty Lands ," VA-NOTES, www.lva.lib.va.us/whatwehave/mil/va16_colonial.htm (last checked January 24, 2006)

By the 1660's, conditions changed in both England and Virginia; fewer people chose to become indentured servants in Virginia. To create a low-cost alternative labor force, slaves were brought involuntarily to raise tobacco and finance the lifestyle in which Virginia colonists wished to live.

Throughout the Eighteenth Century, immigration was still encouraged. Settlement crossed the Fall Line, and the threat of French attack was added to the standard concerns about conflicts with Native Americans on the Piedmont. European migrants, often fleeing poverty in Ireland plus religious conflicts in France and what today is Germany, were offered cheap land as the primary inducement to settle on the frontier.

When the colonial government sold 50 acres per individual immigrant based on treasury rights, it acted as a retailer. The colony's administrative costs were reduced when the colony acted as a wholesaler and provided land in large grants to individuals.

Governor Gooch abandoned the efforts of Governor Spotswood to limit the control of land. Spotswood had recognized that a powerful force of elite "First Families of Virginia" was developing the capacity to resist the efforts of royal governors to implement London's policies.

Large land grants in the 1720's to Alexander Ross, Morgan Bryan, the Van Meters, Robert McKay and Jost Hite reflected Governor Gooch's geopolitical objective to populate the backcountry west of the Blue Ridge with white Protestants who would resist French and Native American incursions. The Governor's Council shifted towards operating as a wholesaler, and those awarded large grants became responsible for recruiting immigrants into Virginia's exposed boderland west of the Blue Ridge.

Governor Gooch was also interested in limiting the extent of Lord Fairfax's proprietary grant. Before the grant was surveyed in 1736, he hoped to set the Blue Ridge as its western boundary.

Starting in the 1730's, many land grants issued in Williamsburg also reflected the profit motives of well-connected members of the Tidewater elite. Tens of thousands of acres of western lands could be acquired at a low cost through a grant from the Governor's Council, then sold in 100-400 acre parcels to immigrants who came from countries in Europe where they had very little opportunity to become landowners.

At first, individuals like William Beverley from Essex County used their influence to obtain land grants from the colonial government. Later,members of the First Families of Virginia created partnerships and organized the Ohio Company, Loyal Land Company, and other assemblages. Those land companies ended up competing against each other, land companies organized in Pennsylvania, and Richard Henderson, a bold individual who organized the Transylvania Company and tried to create a 14th colony.

The members of the Governor's Council who approved large grants to land companies were often associated with the investors in the very same land companies. In the mid-1700's, conflict-of-interest constraints on the actions of colonial officials were weak. There was a significant overlap in family/business connections between the applicants for grants in the 1740's and the colonial officials who awarded grants.

Most large grants were issued prior to the start of the French and Indian War in 1754. At the time. geographic knowledge of the western lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains was poor.

However, it was clear that the population in the colonies was increasing steadily and land hunger was constant. The soils on river terraces in the Mississippi River watershed would be excellent for growing crops once the forests were cleared. Land speculators recognized that demand for western lands was reliable, so the main challenge was to obtain the supply.

There were costs for obtaining the supply; land grants did not involve getting "free" land. There were costs to survey parcels, pay administrative fees to the Secretary of the colony, and to reward agents who recruited settlers and managed sales. Financing costs were a factor as well. Since banks did not offer mortgages in the mid-1700's to land speculators, they had to start with sufficient capital to cover the up-front costs. The profits would come years and decades afterwards; many speculators were trying to build wealth for their children rather than themselves.

Organizing as an investor in a land company helped to share the up-front costs and to offset some of the risks. The risks included the legitimacy of a grant, particularly in the upper reaches of the Ohio River Valley where the boundaries between Pennsylvania and Virginia were undefined. If the Frenh managed to build forts and defend their claim to the entire Mississippi River watershed, no land grant from any English colony would have value.

While the Europeans always expected to displace the Native Americans and force them to keep moving westward, the threat of attack affected the willingness of settlers to pay for land west of the Appalachians. War was a business risk.

Collecting payment for the sale of land was also a challenge. Squatting without paying anyone for land, pre-empting good land and establishing "corn" or "tomahawk" rights to enough acreage to establish a family farm, was a common practice in the borderlands. Land speculators living east of the Blue Ridge struggled to get paid for some of the best property within a grant. County sheriffs, dependent upon the local population for manpower and their support for compliance with a wide range of laws, were not inclined to evict families in response to demands by some distant wealthy person.

After the Governor's Council agreed to a grant, the recipient was supposed to have large tracts surveyed. The surveys were to be delivered to the land office in Williamsburg, which was managed by the Secretary of the colony. Surveys were reviewed there to ensure they did not overlap existing claims. Someone like Lord Fairfax, or another land company, could have agents review the survey and enter a "caveat" if they already owned property within the survey boundaries. Such caveats were resolved either by negotiations or lawsuits. The legal process typically required many years of evidence gathering and court procedures before final decisions were made.

After a land company paid the administrative costs to the land office for reviewing a survey and it was accepted without caveat, it then paid the equivalent treasury right cost per acre and received a patent from the governor. That patent defined who had the legal right to own and sell a parcel, as defined by an accepted metes and bounds survey. An individual or land company with a patent could then subdivide large tracts into small parcels and sell them to individual farmers.

Land companies who purchased large tracts paid low prices per acre, then carved up small parcels in separate surveys and sold those parcels at a relatively high price per acre. When local government for Augusta County was finally made operational in 1745, just 13 men had acquired 85% of the 289,509 acres already transferred into private ownership. Those few men had acquired that land in tracts of 1,000 acres or larger.2

Nathaniel Turk McCleskey, "Across the first divide: Frontiers of settlement and culture in Augusta County, Virginia, 1738-1770," PhD thesis, College of William and Mary, 1990, p.70, https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-6p40-zt04 (last checked January 14, 2025)

Owners of patented land were supposed to pay an annual quitrent per acre, the equivalent of modern property taxes, to the colonial government in Williamsburg. A different tax in titheables (men 16 years of age and older, plus enslaved women of that age) was not based on acres of land owned, and he titheable tax financed the operations of local county officials. The annual titheable tax also funded the local Anglican vestry which provided social services, and paid a minister with those county taxes to provide religious services based on the Book of Common Prayer.

Land speculators dod not pay the annual tax on titheables. That tax burden was absorbed by local residents and owners of enslaved workers/indentured servants based at "quarters" and farming far from the landowner's residence. However, land speculators were supposed to pay quitrents on patented land. Collection of those quitrents and submission of that revenue by local sheriffs was not consistent, but land speculators found a simple way to avoid that tax.

It was common to have surveys processed by the land office, obtain a warrant certifying that the survey had been approved, but not go through the final step and obtain a legal patent. Processing a survey eliminated the risk of conflicting claims and defined specific legal boundaries of land to be transferred into private ownership, and official warrants for land were equivalent to cash in the colonial economy. However, unpatented land remained in the crown's ownership. By not going through the final step and by not getting a deed, land companies avoided triggering the requirement to pay annual quitents to the crown.

Governor Dinwiddie triggered a major dispute when he arrived and tried to force the processing of patents. He simulataneously tried to add a fee (a "pistole" worth 18 shillings) as a personal remuneration for each patent document that he issued.2

Alison Olson, "The Pistole Fee Dispute," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, December 7, 2020, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/pistole-fee-dispute-the/ (last checked Jauary 17, 2026)

Surveying was a political as well as a mathematical exercise. County surveyors had great power to shape who acquired land. They could block small purchasers, or even large purchasers if they were not allies, by not processing surveys or by not identifying available land. The county surveyor also had the power to delay action on survey requests until someone else, preferred by the surveyor, sought to acquire the same land.2

Nathaniel Turk McCleskey, "Across the first divide: Frontiers of settlement and culture in Augusta County, Virginia, 1738-1770," PhD thesis, College of William and Mary, 1990, p.70, https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-6p40-zt04 (last checked January 14, 2025)

In theory, settlers seeking just 100 acres could pay the county surveyor or his deputy to mark out boundaries on vacant land owned by the crown, then take the survey to the land office in Williamsburg and acquire a patent by paying the administrative fees there.

In practice, only the surveyor knew the boundaries of parcels which were still vacant and available. Undeveloped land which appeared available was often already claimed. A person who paid for a survey without knowing about a previous claim could discover that the land office would not process a patent; a rival claimant with a survey filed earlier would enter a "caveat" and block the land sale.

However, settlers seeking a small farm in the backcountry could buy land quickly with the equivalent of title insurance if they purchased land from a land company or individual with a warrant or patent for a large grant. The owners of large land grants could demonstrate that they had a warrant or patent, and were authorized to sell the desired parcel.

There was often a delay of several years between the time a settler built a house and the time the settler acquired title. Land companies and other grantees postponed

Colonial leaders issued large grants to land companies. These were groups of individuals who joined together to gain the opportunity to speculate on western lands. If they could buy low, meet the terms of the grants, and then sell high, then the land companies could turn a good profit and enrich the members. .

In 1753 the Board of Trade in London, which at the time had responsibility for oversight of Great Britain's American colonies, stepped in. It renewed the ban against patenting land in parcels greater than 1,000 acres. Royal officials had determined that colonial governors were being too compliant to requests from wealthy landowners, many of whom served on the Governor's Council, to assert control over the western lands which belonged in theory to King George II.

The 1,000 acre limit imposed in 1753 was relatively easy to evade. Purchasers seeking large tracts would pay for surveys of adjacent parcels that were each 1,000 acres or less in size. Family members and allies would claim those parcels in their own names, then transfer them to one individual. George Washington applied that technique in the 1760's and 1770's in order to acquire large tracts using warrants he had acquired from other French and Indian War veterans.3 "Washington as Land Speculator," Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/george-washington-papers/articles-and-essays/george-washington-survey-and-mapmaker/washington-as-land-speculator/#N_12_; Nathaniel Turk McCleskey, "Across the first divide: Frontiers of settlement and culture in Augusta County, Virginia, 1738-1770," PhD thesis, College of William and Mary, 1990, p.74, https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-6p40-zt04; Turk McCleskey, "Rich Land, Poor Prospects: Real Estate and the Formation of a Social Elite in Augusta County, Virginia, 1738-1770," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 98, Number 3 (July 1990), p.467, pp.464-466, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4249164 (last checked January 14, 2026)

The French and Indian War and then the Proclamation of 1763 interrupted processing of surveys and land sales. Native American claims were erased, at least in the eyes of the British, by the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor, and the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber. However, King George III never issued direction to his royal governors to process the land bounties that he promised to veterans of the French and Indian War. Disputes between Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia regarding charter rights and boundaries in the Ohio River watershed blocked the ability to offer clear title when selling much of the vacant land.

Investors in land companies and other land speculators established personal relationships with Virginia's governors in order to obtain authorization to patent acreage, but with minimal success. In the 1760's and 1770's land companies sought to get royal confirmation of their primary asset, the right to claim and then sell land. Instead, British policy towards the colonies hardened after resistance to the Stamp Act in 1765 expanded into objections to other taxes and policies adopted by Parliament and King George III.

At the outbreak of the American Revolution, local courts and other offices ceased to function. The land office in Williamsburg stopped approving surveys.

In 1779 the General Assembly of the newly-independent Commonwealth of Virginia passed a land law and opened a state land office. Restoring the process for patenting western lands was a priority in part because the General Assembly had promised land bounties in order to recruit soldiers to serve in the Continental Army.

The new land office was faced with extraordinary confusion regarding unprocessed claims and surveys by different land companies and others claiming western lands. The law declared valid the surveys approved before 1778 by "accredited" county surveyors, those who had been licensed by the College of William and Mary and appointed officially. Many of the county surveyors hd worked for the Greenbrier and Loyal Companies, while other land companiesculd not get their claims validated.

In addition, surveys for parcels 400 acres or smaller were also legalized so long as the survey had been completed by 1763. Premption claims for settlers who had established themselves before 1778 were also allowed. To further accommodate the people who actually moved into the borderlands, they were also allowed to purchase an additional 1,000 acres. The General Assembly appointed commissioners in four separate districts in the Ohio River watershed to determine the validity of other claims, primarily by land speculators.3

"Land Disputes in Western Virginia," Wythepedia, William and Mary Law Library, https://wythepedia.wm.edu/index.php/Land_Disputes_in_Western_Virginia (last checked January 18, 2026)

The legislature also granted Richard Henderson 200,000 acres to resolve his claim for 20,000,000 acres. He had purchased what as much of Kentucky from the Cherokee in the 1775 Treaty of Sycamore Shoals. The land grant was placed on the western end of Kentucky, ensuring that the Loyal Land Company and the Greenbrier Company would not be impacted.3

"The Treaty of Sycamore Shoals," Tennessee State Museum, September 29, 2025, https://tnmuseum.org/junior-curators/posts/the-treaty-of-sycamore-shoals; "Notes and Documents relating to the Transylvania and Other Claims for Lands under Purchases from the Indians [Editorial Note]," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-02-02-0033-0001 (last checked January 18, 2026)

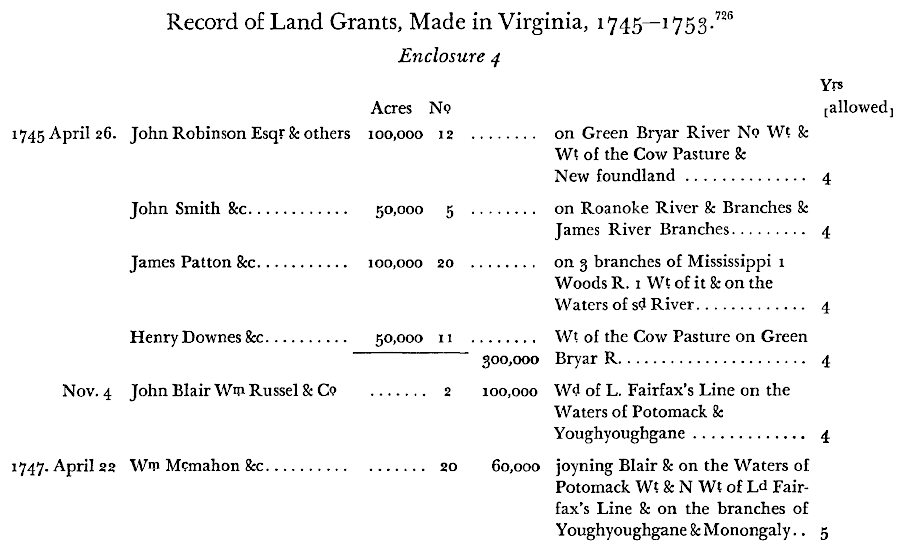

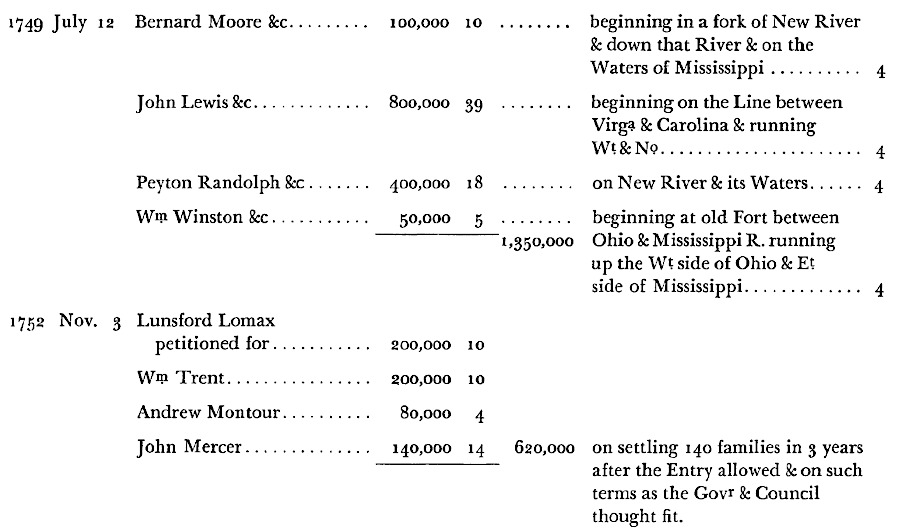

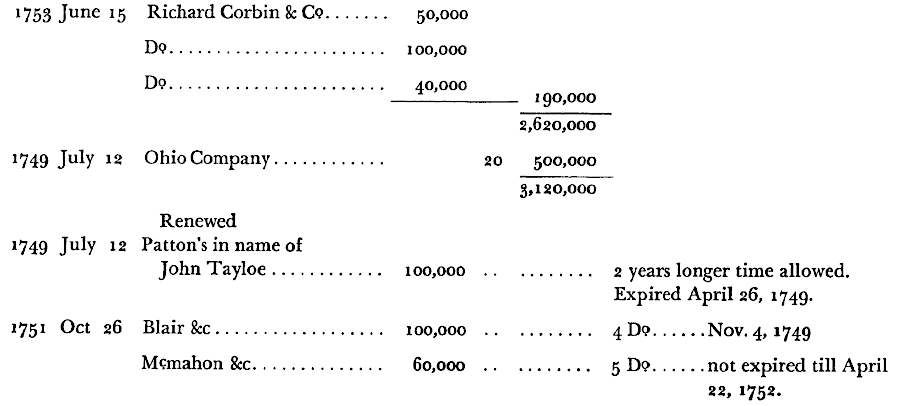

multiple well-connected land speculators sought land grants from the Governor's Council in Virginia and royal officials in London

Source: George Mercer Papers: Relating to the Ohio Company of Virginia, Enclosure 4 Record of Land Grants, Made in Virginia, 1745—1753