William Beverley's mansion house was later used as the Staunton Public Library

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Governor Gooch decided to issue large land grants west of the Blue Ridge to encourage settlement by men willing to be loyal to the Virginia colony. The governor wanted to provide a line of defense against the French who claimed ownership of the Mississippi River watershed, and against various Native American groups who might ally with the French and consuct raids into the Piedmont.

Lord Fairfax's agents protested the authority of the colonial officials in Williamsburg to dispose of land within the boundaries of the Fairfax Grant, including lands west of the Blue Ridge which extended to the headsprings of the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers. The dispute delayed final issuance of tile to grants made to John and Isaac Van Meter and to Joist Hite, in the lower (northern) part of the Shenandoah Valley.

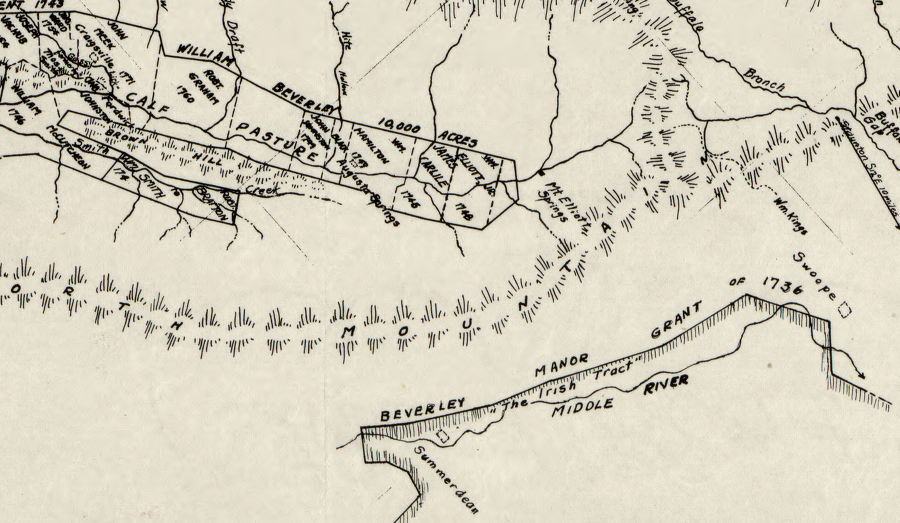

On September 6, 1736, as surveyors were marking the boundaries of the Fairfax Grant, Governor Gooch and his Council in Williamsburg approved a 60,000 acre grant to William Beverley. That acreage was almost equal to the size of York County. Initially Beverley had several partners, but by 1741 he was in total control.

The grant authorized Beverley to pay the county surveyor to mark off tracts. With the survey documentation, Beverley could then go the Secretary of the colony and purchase the acreage. The fee to the Secretary covered the cost of issuing patents for the surveyed tracts. The patent started the chain of title in private ownership, enabling Beverley to have smaller parcels surveyed and sell chunks of land to individual settlers at whatever price he could negotiate.

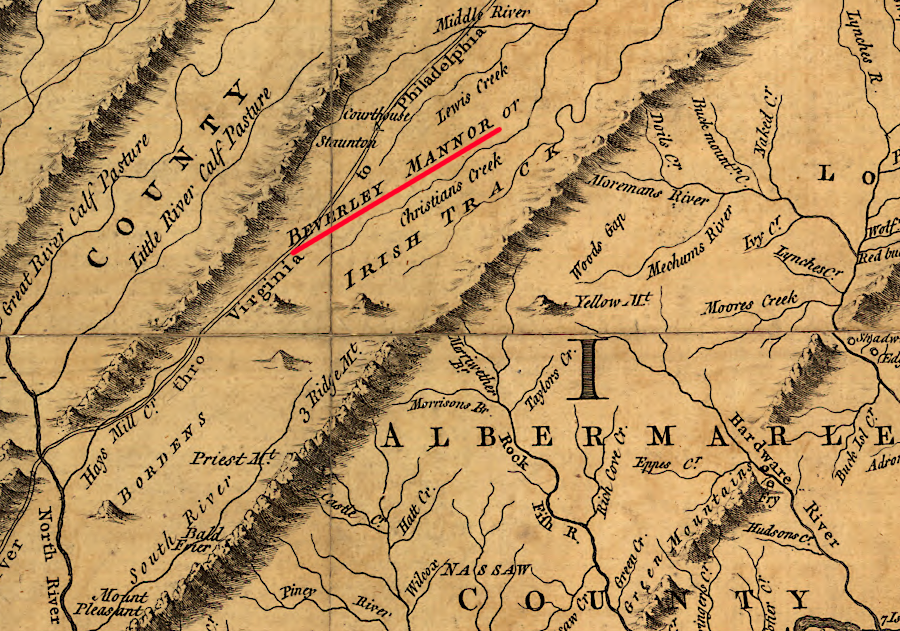

The boundaries of the Beverley grant, including much of modern-day Augusta County and the city of Staunton, were located south of the Fairfax Grant "back line" that connected the headsprings of the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers. Beverley's grant was one of several that tranferred over 650,000 acres of the colony's land, half of the modern Augusta County, into private ownership before 1770. In 1739 Benjamin Borden was given a 100,000 acre grant, soon called the Irish Tract, just south of Beverley's grant.

William Beverley was a member of the gentry, the elite Virginians who acquired land, slaves, wealth, and status. His father Robert Beverley had published The History and Present State of Virginia, In Four Parts in 1705. In 1716, he had accompanied Governor Spotswood and the the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe into the Shenandoah Valley. 1

William Beverley inherited his father's estate, including the plantation house Blandfield in Essex County. He was elected to the House of Burgesses from Orange County and then from Essex County. In 1746, he helped survey the Fairfax Line as a commissioner for Lord Fairfax.

Beverley's status may explain why the Governor's Council was so generous when it was told on August 23, 1736 that the surveyor had miscalculated when drawing the lines. Instead of enclosing 60,000 acres, surveyor Robert Brooke had established boundaries enclosing 118,491 acres - almost twice what had been originally authorized. The error would appear to have been intentional, perhaps because Brooke had recently been chastised for completing a survey which was 50% smaller than intended.

Beverley was allowed to retain his claim to all the land within "the most profitable surveying error of the era." 2

Beverley built a mill on a stream and then a mansion house. His tract became known as Beverley's Manor, though he had no feudal rights to govern the residents who settled there. Though he built an impressive brick house, William Beverley personally chose to live at his family plantation in Essex County. The mansion house within the grant later became the site of the Staunton Public Library, and is now a private school.3

William Beverley's mansion house was later used as the Staunton Public Library

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

According to the terms of the grant, Beverley could patent 1,000 acres for every family that he recruited to settle on his grant. Beverley and Benjamin Borden both recruited Scotch-Irish settlers from Pennsylvania and Ireland. The two grantees generated income from their land grants when they had actual settlers and qualified for a patent. The initial settlers were often too poor to purchase a parcel, but once a patent was issued Beverley had the legal right to sell that parcel to anyone..

The settlers included many Presbyterians who had fled northern Ireland. The English government had depressed the Irish economy by the 1699 Woolen Act, banning the export of textiles except across the Irish Sea to England. The 1703 Test Act had required everyone to convert to the established Anglican Church in order to vote, and constrained the Presbyterian churches in Ireland.

Starting in 1717, after English landlords raised rents in Ireland, nearly 50,000 people emigrated to North America over the next sixty years. A primary destination was Pennsylvania, where William Penn and his Quakers had created a colony that welcomed different religious faiths. Virginia became a destination for ultimate settling because land in the Shenandoah Valley in 1740 was sold by the land agents of Beverley and Borden at 7 pence/acre, less than 1/30th of the 1 pound or 1 pound 10 shillings per acre price in Pennsylvania.4

William Beverley arranged for an Irish ship captain, James Patton, to recruit families to settle the grant. In exchange, Patton would be paid in land. It is unclear how Beverley was acquainted with Patton, but it is possible that the two were somehow associated with smuggling tobacco into Britain.

Patton may have sailed across the Atlantic Ocean 25 times. In an August 9, 1737, letter Beverley wrote to Patton:5

Beverley also sought assistance from John Lewis, another immigrant from Ireland. Patton and Lewis were offered land, not cash, for their efforts. John Lewis moved his family from Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1732 and was squatting on the land granted to Beverley.

Beverley hired John Lewis as his land agent. After 1738, Beverley lived all the time in Essex County rather than in his new house on his grant. Lewis acquired 2,000 acres from Beverley on what today is known as Lewis Creek and built a house he called Bellefonte.

Perhaps with assistance from William Beverley, in 1743 and 1744 James Patton and John Lewis obtained grants for roughly 30,000 acres on the Calfpasture River.6

parcels surveyed for William Beverley included land on the Calfpasture River

Source: Library of Congress, Colonial land patents and grantees: Calfpasture Rivers, Augusta County, Virginia (by Meredith Leitch, 1947)

When Augusta County was formalized in 1745, John Lewis' son Thomas Lewis was given the lucrative and powerful job of county surveyor. He kept it until 1777. Since all parcels could be patented only after survey, Thomas Lewis was able to reward his allies by completing their surveys first so they obtained the best lands in Augusta County.7

Benjamin Borden's 92,200 acre Irish Tract was located south of William Beverley's 118,491 acre grant in the Shenandoah Valley

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

Though Beverley was a traditional Anglican, a member of the Church of England, many of the settlers in the Shenandoah Valley did not belong the established church. James Patton and John Lewis, top officials in Augusta County, were Presbyterians. In 1738, as Presbyterians began to migrate south along the Great Road (later US 11 and then I-81) and fill up the Shenandoah Valley, the Presbyterian Synod of Philadelphia got Governor Gooch to affirm that the Virginia colony would not discriminate against nonconformists.

The governor only required that the dissident Presbyterians and other non-Anglicans register the location of their religious meeting places. Presbyterian churches were built with private funds; the Anglican churches were constructed with public tax revenue. The first Presbyterian minister, Rev. John Craig, settled near Lewis Creek in 1740.

An Anglican vestry was responsible for some social services, such as the care of orphans, so non-Anglicans did receive some benefits from the church taxes they were required to pay. The Anglican parish in Augusta County was organized in 1746 and the first Anglican minister, Rev. John Hindman, arrived in 1747. The 200 acre glebe, which generated revenue for the minister to support his salary, was purchased in 1748.

Presbyterian landowners in the area dominated the vestry, and ministers from the two faiths preached on separate Sundays in the Augusta County courthouse. Choosing dissenters for an Anglican vestry caused some concern, but evidently was acceptable to William Beverley. A petition to allow only Anglicans to serve was rejected by the General Assembly.8

A large number of German-speaking settlers arrived after the Scotch-Irish. The first Lutheran Church was built in 1780.9

When William Beverley received his grant, the land was in Orange County. That courthouse was east of the Blue Ridge, so traveling to it in order to process land deeds and deal with lawsuits was burdensome. The General Assembly anticipated population growth by chartering Frederick and Augusta counties in 1738, but recognized that the current population was insufficient to pay the taxes required to build a courthouse and pay justices of the peace and other county officials.

The militia was organized starting in 1741, but Augusta County justices of the peace were not appointed until 1745. Beverley donated 25 acres for the courthouse lot, but some settlers opposed the location because there was no spring nearby. The controversy was settled by the General Assembly in which Beverley was influential, and his preference for the site of the county seat was selected. He had already built a log cabin structure to serve as the courthouse.

The new community was known first as Augusta Court House. In 1761, the town was established and named Staunton after the wife of Governor Gooch.10